Feed aggregator

Anybody have fursona stories?

Gimme some background to your character, I want to hear your fresh and cool ideas. Who are they? What species are they? Where were they born? Where do they live? What about them defines them? Was there a struggle or event that made them who they are? [I apologize if it takes a while for me to give you feedback on your hard work, I promise I will, I'm just a very busy furry]

submitted by MRjarjarbinks[link] [69 comments]

Shady business with FurFling?

So, I subscribe to FurFling. I've met some cool people through it and had some interesting chats, so I figured why not subscribe.

The thing is that FF only allows you to read private messages you receive if you're subscribed.

I used PayPal to subscribe and the card I used as my backup payment expired. I was not able to get a new one before my subscription was canceled due to being unable to pay.

Since the subscription canceled, I have been receiving PMs like crazy. At least one a day, sometimes as many as 3. This strikes me as odd, because I haven't logged on to FF in a couple months. When you search for people on FF, it automatically sorts by most recently logged in, so I would likely be way down in the search results.

So the way I see it, one of two things is happening.

1 - they sort recently expired subscribers toward the top to encourage others to message them and hopefully get them to resubscribe.

2 - they use fake accounts and message expired subscriptions to get them to resub.

Has anyone else encountered something like this?

EDIT: I forgot to clarify that there have been no messages since the last time I was active, up until my subscription expired.

submitted by jimmysaint13[link] [8 comments]

Younger Brother Needs Her Guidance as He Enters Puberty and Explores His Furry Side

I just found out my 13 year old younger brother is a furry what advice can you give me that will help me be a better sister?

I am female 22 years old and I live out of home. My brother lives with my single mum and I visit them weekly. I used to live with them and contribute to looking after him like a parent due to the age gap.

I have been crying non-stop since I found out. Mostly because he is so incredibly young to even know what specific fetishes are. I know boy seek out pornography when they hit puberty. But I guess I am so shaken because he's just so young.

I'm trying my best to understand him. I know there is a difference for people that enjoy the art and fandom. Then there are zoophiles. I have seen some content he posted on minecraft forums that he is sexually attracted to anthro dragons and birds.

I guess my issue here is if he was say 17 and I found this out then I probably wouldn't care. But he is so incredibly young, he is still a child!

My sexual exploration was BDSM when I was seventeen. My mum flipped out, slapped me in the face and took my computer away. She constantly monitored my MSN conversations by hacking me and saving my history. That’s now in the past but now that my brother has a computer in his room my mother doesn't even care that he goes on 4chan or who he is talking to online. It’s gone from being controlling with me to having no parenting boundaries whatsoever with my younger brother.

I know this is a “laundry bag” of stuff but I am desperate for guidance. Please help make the best choice for him.

When my brother asked my mum for a computer in his room I told her that.

Anonymous

* * *

Dear Anonymous:

You are a good sister for caring about your brother. As I started to read your letter, my first reaction was, “Hold on a second; don’t assume this is about sex,” but then you continued and said you noticed he was sexually attracted to some furry art. So, my second thought is that, while some of this might be about sex, it also might be about him just enjoying furries in general.

But, let’s face it, many young people are initially attracted to furry art because of sex. That’s how, to be honest, I first stumbled upon it, and while I am about much more than just furporn now, it is still an attraction. So, let’s talk about it honestly.

You worry that your brother is only 13, but, hey, that is when puberty sets in for many people and so it is not surprising at all that he is thinking about sex now. The second issue is accessibility. Thanks to the Internet, people, especially young people under 18, now have easy access to a lot of stuff that, before all this technology, could only be seen by going to a dirty book store or porno house or strip club, where admission was guarded by, often literally, guards. So kids your brother’s age had no way to see it, unless they found dad’s Playboys or a friend got them some copies of it.

On the Internet, it is not just furry X-rated art that is easy to view, but pretty much anything. If your brother were not looking at naked furries, he’d probably be looking at something else of an adult nature. As to furry sites, it is my personal opinion that the adult content should be age restricted and pay-only (with a credit card), which would stop many minors (and some cheap adult furries) from viewing it—the latter probably being the reason that these sites don’t impose restrictions as they would lose much of their traffic and, consequently, advertisers. But since I am not a site admin at FurAffinity or any other furry art site, there’s nothing I can do about it. (And, yes, I do advertise on FA because it gets me traffic, and, frankly, it can lead to an open and helpful discussion about sex, just as with this letter).

It is really up to the parent to control such viewing. The best way to do this is to have any and all computers placed in the living or dining or kitchen areas of the house, not the kid’s bedroom. Parents need to take an active role in what their children are viewing online, and this is not just about porn but lots of other nasty stuff that kids can be vulnerable to, from cults to hate groups to online predators.

So, you might ask, why did you get heavily supervised and your brother did not? It’s possible that, as with many mothers, the first child is the most fretted over and that the parent relaxes some by the time the second or third child comes along; it is also possible that it is because you are a girl who is seen as vulnerable, while, on the other hand, “boys will be boys.” Not saying that’s right thinking, but it is common thinking.

You have already suggested to your mother that she be more watchful about your brother’s online behavior. You might bring up those possibilities mentioned above when next you talk to your mom and maybe that would open her eyes up a bit.

Let’s assume, then, that your brother will continue to look at furry porn, but why is that disturbing you so much? You, who explored the world of BDSM as a teenager, must realize that teenagers, especially, are going through the phase of exploring their sexuality, and furriness is surely no more disturbing than bondage, domination, and sado-masochism. Actually, depending on the furporn, it is less disturbing than BDSM, especially when you dispel yourself of the erroneous notion that there are a lot of zoophiles in the fandom. In fact, there are no more zoophiles in the furry population then there are in the mundane world, and they are a tiny, tiny, tiny minority.

Just to be clear, a zoophile is someone who is sexually attracted to a real animal; furries, importantly, are not necessarily attracted to anthropomorphized characters in a sexual manner, and, if they are, it is not about animal sex, it is about certain appealing features such as fur and tails.

To say that a furry wants to make love to a dog is like saying that someone into leather harnesses and chaps wants to screw a cow, or that people attracted to edible underwear want to have intercourse with a bag of Twizzlers. It’s not at all the same thing.

So, my final advice to you is to calm down a little bit, and, like the good sister you are, talk to your brother about going through puberty (I’m assuming that your mother is not willing to). Part of his vulnerability is due to the fact that he has no father figure in his life. You can be a father surrogate, while doing so without going into anatomical detail, and just have an open conversation that everyone, including you, has gone through a stage of sexual exploration and that is okay, even if he might be going through it earlier than expected. The important thing to remember is to remind him to always be kind to others (never forgetting that, although you are in cyberspace, there is a real person on the other end of the conversation) and to practice safe sex until such a time comes along that he finds someone he really trusts to be intimate with. (The safe sex talk is critically important, and even though he might protest that “I know all that stuff,” a deeper dialogue will likely reveal that he really doesn’t—you might be surprised by what some young people believe about safe sex these days.)

At thirteen, your brother is at a very vulnerable and impressionable age. I wish he had a parent to help guide him, but, barring that, if you are willing, he could really use a great sister like you to ease any confusion he may be having right now, just as you turned to an older advice columnist for a little help.

Thank you for writing, and good luck!

Papabear

Younger Brother Needs Her Guidance as He Enters Puberty and Explores His Furry Side

I just found out my 13 year old younger brother is a furry what advice can you give me that will help me be a better sister?

I am female 22 years old and I live out of home. My brother lives with my single mum and I visit them weekly. I used to live with them and contribute to looking after him like a parent due to the age gap.

I have been crying non-stop since I found out. Mostly because he is so incredibly young to even know what specific fetishes are. I know boy seek out pornography when they hit puberty. But I guess I am so shaken because he's just so young.

I'm trying my best to understand him. I know there is a difference for people that enjoy the art and fandom. Then there are zoophiles. I have seen some content he posted on minecraft forums that he is sexually attracted to anthro dragons and birds.

I guess my issue here is if he was say 17 and I found this out then I probably wouldn't care. But he is so incredibly young, he is still a child!

My sexual exploration was BDSM when I was seventeen. My mum flipped out, slapped me in the face and took my computer away. She constantly monitored my MSN conversations by hacking me and saving my history. That’s now in the past but now that my brother has a computer in his room my mother doesn't even care that he goes on 4chan or who he is talking to online. It’s gone from being controlling with me to having no parenting boundaries whatsoever with my younger brother.

I know this is a “laundry bag” of stuff but I am desperate for guidance. Please help make the best choice for him.

When my brother asked my mum for a computer in his room I told her that.

Anonymous

* * *

Dear Anonymous:

You are a good sister for caring about your brother. As I started to read your letter, my first reaction was, “Hold on a second; don’t assume this is about sex,” but then you continued and said you noticed he was sexually attracted to some furry art. So, my second thought is that, while some of this might be about sex, it also might be about him just enjoying furries in general.

But, let’s face it, many young people are initially attracted to furry art because of sex. That’s how, to be honest, I first stumbled upon it, and while I am about much more than just furporn now, it is still an attraction. So, let’s talk about it honestly.

You worry that your brother is only 13, but, hey, that is when puberty sets in for many people and so it is not surprising at all that he is thinking about sex now. The second issue is accessibility. Thanks to the Internet, people, especially young people under 18, now have easy access to a lot of stuff that, before all this technology, could only be seen by going to a dirty book store or porno house or strip club, where admission was guarded by, often literally, guards. So kids your brother’s age had no way to see it, unless they found dad’s Playboys or a friend got them some copies of it.

On the Internet, it is not just furry X-rated art that is easy to view, but pretty much anything. If your brother were not looking at naked furries, he’d probably be looking at something else of an adult nature. As to furry sites, it is my personal opinion that the adult content should be age restricted and pay-only (with a credit card), which would stop many minors (and some cheap adult furries) from viewing it—the latter probably being the reason that these sites don’t impose restrictions as they would lose much of their traffic and, consequently, advertisers. But since I am not a site admin at FurAffinity or any other furry art site, there’s nothing I can do about it. (And, yes, I do advertise on FA because it gets me traffic, and, frankly, it can lead to an open and helpful discussion about sex, just as with this letter).

It is really up to the parent to control such viewing. The best way to do this is to have any and all computers placed in the living or dining or kitchen areas of the house, not the kid’s bedroom. Parents need to take an active role in what their children are viewing online, and this is not just about porn but lots of other nasty stuff that kids can be vulnerable to, from cults to hate groups to online predators.

So, you might ask, why did you get heavily supervised and your brother did not? It’s possible that, as with many mothers, the first child is the most fretted over and that the parent relaxes some by the time the second or third child comes along; it is also possible that it is because you are a girl who is seen as vulnerable, while, on the other hand, “boys will be boys.” Not saying that’s right thinking, but it is common thinking.

You have already suggested to your mother that she be more watchful about your brother’s online behavior. You might bring up those possibilities mentioned above when next you talk to your mom and maybe that would open her eyes up a bit.

Let’s assume, then, that your brother will continue to look at furry porn, but why is that disturbing you so much? You, who explored the world of BDSM as a teenager, must realize that teenagers, especially, are going through the phase of exploring their sexuality, and furriness is surely no more disturbing than bondage, domination, and sado-masochism. Actually, depending on the furporn, it is less disturbing than BDSM, especially when you dispel yourself of the erroneous notion that there are a lot of zoophiles in the fandom. In fact, there are no more zoophiles in the furry population then there are in the mundane world, and they are a tiny, tiny, tiny minority.

Just to be clear, a zoophile is someone who is sexually attracted to a real animal; furries, importantly, are not necessarily attracted to anthropomorphized characters in a sexual manner, and, if they are, it is not about animal sex, it is about certain appealing features such as fur and tails.

To say that a furry wants to make love to a dog is like saying that someone into leather harnesses and chaps wants to screw a cow, or that people attracted to edible underwear want to have intercourse with a bag of Twizzlers. It’s not at all the same thing.

So, my final advice to you is to calm down a little bit, and, like the good sister you are, talk to your brother about going through puberty (I’m assuming that your mother is not willing to). Part of his vulnerability is due to the fact that he has no father figure in his life. You can be a father surrogate, while doing so without going into anatomical detail, and just have an open conversation that everyone, including you, has gone through a stage of sexual exploration and that is okay, even if he might be going through it earlier than expected. The important thing to remember is to remind him to always be kind to others (never forgetting that, although you are in cyberspace, there is a real person on the other end of the conversation) and to practice safe sex until such a time comes along that he finds someone he really trusts to be intimate with. (The safe sex talk is critically important, and even though he might protest that “I know all that stuff,” a deeper dialogue will likely reveal that he really doesn’t—you might be surprised by what some young people believe about safe sex these days.)

At thirteen, your brother is at a very vulnerable and impressionable age. I wish he had a parent to help guide him, but, barring that, if you are willing, he could really use a great sister like you to ease any confusion he may be having right now, just as you turned to an older advice columnist for a little help.

Thank you for writing, and good luck!

Papabear

Opinions on hybrids and furs making their own species?

Just curious as to what other fuzz-butts make of them, it seems like a hot topic in this fandom.

submitted by Roryous[link] [12 comments]

FaceRig DevBits 10: W.I.P Cartoon-y wolf.

He Needs to Come to Terms with His Sexuality and Then Reevaluate His Marriage

If you're looking for something to read you should check out M.C.A. Hogarth

I've been reading her books for a while, and she has become my favorite author. Not all of it is furry, but most of it has at least a few furry characters. She has a few different series. I had a little trouble figuring out what order to read them in, her site really helps Where do I start. She also does her own art, I picked up a couple of her prints. A couple of her short stories are free on amazon if you want to see her writing style.

submitted by iggy_koopa[link] [comment]

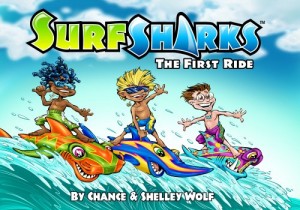

Big Teeth, Big Waves

Shelley Wolf is a creator of magic tricks for kids. Her husband Chance Wolf is a well-known comic book illustrator for titles like Spawn. When the two of them noticed how their son was getting really into shark lore, they decided to use that as an inspiration for a new series of books for kids. And so the Surf Sharks were born. The idea is simple: Three beach kids and three talking sharks hook up to ride the waves, have adventures, and learn more about our oceans. Surf Sharks: The First Ride just came out in hardcover from Surf Sharks Inc, and it’s available on Amazon. The creators also have a Surf Sharks web site with the books and other collectible shark stuff available.

image c. 2014 Surf Sharks Inc