Feed aggregator

Mickey Go Local – Rainforest Hunt

Disney Southeast Asia [1] has a new Mickey Mouse web series that draws heavy inspiration from Paul Rudish [2]'s rather brilliant series [3]. While not at the same level of budget they do seem to manage well with what they have and the character designs are rather cool. Quite cute. [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Disney_Channel_(Southeast_Asian_TV_channel) [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Rudish [3] https://disney.fandom.com/wiki/Mickey_Mouse_(TV_series)

View Video

The Shadybug

Another cute animated commercial for the Netherlands based ASN bank [1] where they highlight the idea of not taking money from dictators. I gotta say this would be an interesting sequel to bugs life ... just saying. [1] https://www.asnbank.nl/home.html

View Video

Rukus movie review

This unusual movie got 5 support articles before I was ready for a personal review. It’s hard to nail down, so the work got really labored over, but it deserves the effort. – Patch

Rukus was an artist from Florida who committed suicide in 2008 at age 23. He was a mercurial muse to his friends. Linear storytelling about him could make a sad movie, but Rukus comes from many directions. It overlaps documentary of him, with his boyfriend reflecting on their relationship, and his friendship with film maker Brett Hanover. His enigmatic presence weaves through Hanover’s personal life, which goes from trouble with OCD to finding completion in relationships and art. The life of Rukus becomes points on a trajectory of escape from pain.

The directing style frames lo-fi video with dramatized memories, daydreams and fiction from Rukus. They’re re-enacted by younger and older stand-ins for him, and voiced with animation. It’s one of those arty movies that doesn’t easily boil down to one commercial line, but it’s directed with purpose. When the pieces don’t fit together neatly, the negative space holds a chewy assortment of themes.

There’s repressed abuse, disconnection, and love outside of hetero norms. It touches on conflict with anti-gay religion in the Southern US, but it’s more involved with a setting in furry fandom. Furries have a loveably eccentric subculture of fans for talking-animal media that appears in fantasy art by Rukus, internet role-play, a hotel convention, and a stage play. Those feed the human connections in the movie. You also get to see a costumer called a “whore bear” and a moment of tender toes-in-nose contact that turns into crosswired love.

The movie is outstanding for merging fiction and documentary while drawing from a subculture rarely seen in any feature film. It premiered at the San Francisco Independent Film Festival, where furries came for group fursuiting (with full body costumes that make unique “fursonas”). That’s sort of like how Comic Con cosplayers emulate Hollywood superheroes, but those don’t keep their powers when the movie ends.

Rukus casts animal shadows behind misfits who play muses for each other, and delivers bittersweet satisfaction. You can see it now on rukusmovie.com.

Just watched Rukus on Vimeo – an intersection of the furry world and the indie film circuit I never expected to witness. But I loved it! https://t.co/rKOvjsLJGv

— Apollo (@Apollo_Wolfdog) October 17, 2019

Lots to process tonight. I still miss him.

— Vulp-o-Matic 3000 (@triadfox) October 19, 2019

(@triadfox) October 19, 2019

More reading between the lines — Figurative bridges and liminal places

There’s 6 bridges crossing the San Francisco Bay. The Golden Gate is in the most movies. Outside my window, the Richmond-San Rafael bridge is glittering with traffic. In 1964, a troubled woman stopped her car in the lane there, got out, and leapt to her death. A journey cut short like that changes those left behind.

She was the wife of sociologist Erving Goffman. He focused on microsociology (personal relations between individuals) and symbolic interactionism. That’s about the theater of everyday life, and how people manage impressions they give to others. It can involve not feeling at home in your own skin, hiding insecurity or depression behind smiles, or role-play that helps make bridges to other people.

Goffman avoided publicizing his life, but the loss led him to write crypto-biographical work. He studied insane asylum inmates for a paper about stigma, mental illness, and institutionalization called The Insanity of Place:

Although the author does not make direct references to himself, he appears to be drawing on his own painful experience… It is hard to avoid the impression that we are dealing with a “message in a bottle” intimating how the author coped with a personal tragedy at a crucial junction in his life.

Brett Hanover described Rukus as happening in liminal space between people: social media and virtual worlds, punk houses in the south, and furry fandom hotel conventions. They’re temporary sanctums of liberation. Contrast with what Goffman called a total institution (a place cut off from the wider community, where people lead an enclosed, formally administered life.)

Rukus brings sanity to displacement felt by it’s subjects. Hanover gives his own biographical view that puts heart in the transitions from view to view. In one scene, the boyfriend of Rukus tells how he was found dead. It segues to a child stand-in telling his fantasy story to Hanover, which pulls out to show the movie crew. It lightens what came before, and loops back to where the movie started. Friends and animal shapes become ushers for Rukus to cross a bridge, and the hole he left is filled with elegaic spirit.

A critical look at the spirit of the movie might ask if it has to do with the zeitgeist. Maybe a little, when current news and politics has so much struggle about border walls and who belongs in places.

The insanity of place came up on Nextdoor, the neighborhood based social media platform. For the bridge outside my window, a pedestrian-bike lane was attacked as a waste, like everyone would be happy with just cars. The theme was “stay in your lane.” That drama fuels Best of Nextdoor, a misanthropic comedy channel with 8 times more followers than the company’s (and an ironic PR thorn in their side). When neighbors are jerks on social media, sometimes all you can do is laugh.

That ties to one of the year’s most talked about movies, Joker, with a sad clown who’s isolated and powerless in a degrading city. There’s a key scene with subway traffic where he violently fights bullies to gain his power, leading to media sensationalizing. The movie’s budget and PR force it to power over public notice, unlike Rukus with it’s intimate use of role-play.

The media ties to one more ingredient about the furries in Rukus. They’re shy about exposure from a history of tabloids exploiting them as freaks. It’s a small movie that dignifies with politics of caring, instead of forcing a message. We need more personal media like this about people crossing bridges together and finding their place.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

Werewolf The Apocalypse: Earthblood

Finally a video game version of White Wolf Publishing tabletop RPG: Werewolf the Apocalypse [1]! I have all the questions about this but at least it looks more like the original version of the game where the pack is fighting against the forces of the Wyrm [2] and corporate environmental disaster. "With his former pack in danger, Cahal returns to find Endron, the energy arm of Pentex [3], installing an extraction site and destroying the forest around his Caern." [1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Werewolf:_The_Apocalypse [2] https://whitewolf.fandom.com/wiki/Wyrm [3] https://whitewolf.fandom.com/wiki/Pentex

View Video

Oh Fiddlesticks! Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra looks to hire fursuit creator for mascot costume

Winter Weight

These bear based commercials have been an ongoing ad campaign of SCANA Energy [1] that's been going on for a few years and here are the latest. I really dobelieve more companies should use spokes-bears. https://youtu.be/bU2Ui7CcRNY [1] https://www.scanaenergy.com/

View Video

TigerTails Radio Season 12 Episode 06

Furry support: Good Furry Award open for nomination, MidAnthro launches scholarship.

In a group that loves supporting itself and its creators, funding is key. Some furry fandom activity can be a self-sustaining occupation, like creating art or fursuits. It can be nearly impossible for most fandom event organizing or writing. Corporate sponsorship is treated as toxic; crowdfunding is never a guarantee. It’s why things work the way they do, such as *ahem* the time-consuming work of news writing for nonprofit community benefit.

In a group that loves supporting itself and its creators, funding is key. Some furry fandom activity can be a self-sustaining occupation, like creating art or fursuits. It can be nearly impossible for most fandom event organizing or writing. Corporate sponsorship is treated as toxic; crowdfunding is never a guarantee. It’s why things work the way they do, such as *ahem* the time-consuming work of news writing for nonprofit community benefit.

Awards that support furries who qualify are very rare. I’d seen flyers at cons for a furry writer’s residency program (although details aren’t turning up), and then there’s the Good Furry Award.

The Good Furry Award was established in 2018 by Grubbs Grizzly. It gives annual recognition to one winner for outstanding spirit in the furry community. The first one went to Tony “Dogbomb” Barrett. The winner gets a crystal trophy of recognition and check for $500 to use for anything they want. Grubbs says he made it because:

It seems to me that every time something negative happens in the fandom, people focus on that too much to the point of giving the entire fandom a bad reputation. Rather than paying attention to the few furries who cause trouble, I would like us all to focus on furries who do good things and are good people. Let’s give those furries some attention instead!

Nominations are open now. You can do it here: http://www.askpapabear.com/good-furry-award.html

The Cobalt The Fox Memorial Scholarship from Mid-Atlantic Anthropomorphic Association, Inc.

An annual $1000 educational scholarship is coming from The Mid-Atlantic Anthropomorphic Association, a Maryland nonprofit that organizes events like Fur the ‘More and Fur-b-Que. It honors Cobalt The Fox, their staffer who passed away in October 2017.

Who will it support? Details are pending for how to apply. Fur the ‘More’s chair Kit Drago told me: “it will likely be competitive. The application process is expected to have several criteria and questions as well as an essay.” (I wonder if the criteria could favor students in art or things like environmental/animal science, but wait for updates.)

The press release:

The Mid-Atlantic Anthropomorphic Association, Inc. (“MidAnthro”) is pleased to announce a new program which directly contributes to the furry community.

For MidAnthro staff, volunteers, and executives, the furry fandom has been a welcoming, warm, and supportive home. Whether each of us has been here for a few weeks or for decades, we’ve gained lifelong friendships, learned valuable lessons, and experienced the positive power of a diverse, creative community.

MidAnthro’s mission is to promote charitable giving, social responsibility, and education in creative disciplines via community-driven events. We have a vested interest in making this mission a reality for our fellow fandom denizens. In the words of our flagship program event, Fur the More, we want to “Go Further and Do More”.

David Gonce, better known as Cobalt to his friends, was an inquisitive, charitable, and supportive member of the furry community. Not only was Cobalt a staff member for MidAnthro events, but they were also a volunteer at for the Community Fire Company of Perryville. Cobalt, despite his positivity, abruptly left us on October 7, 2017. His presence, positivity, and friendship have been missed by everyone in the organization since then.

In furtherance of our goals as a non-profit organization, to help the community we so love, enjoy, and embrace with open arms, and to honor someone from that community who we unexpectedly lost two years ago, we are launching the David “Cobalt the Fox” Gonce Memorial Scholarship. This scholarship program is our way of commemorating Cobalt’s charity, kindness, and inquisitive nature.

The scholarship is open to anyone in the furry community pursuing an educational program at an accredited technical school, college, university, or training program and is valued at $1000 for one recipient for the current year.

For more details on the scholarship program, requirements, and the application process as it continues to develop, please visit http://www.midanthro.org.

Thanks for talking about this. My goal is and always have been to try and help our community grow, and be a positive light in a world often living in shadows.

We will be looking for volunteers interested in serving on a scholarship committee soon. https://t.co/y2B4jc7YgT

— Kit Drago  (@kitdrago) October 21, 2019

(@kitdrago) October 21, 2019

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

What A Versatile Little Alien

Recently at Los Angeles Comic Con we came across the work of Jonathan Hallett. He’s a career storyboard artist for a living, but in the original art he creates on the side he has a very special affinity for the alien half of Disney’s Lilo & Stitch — so much so that he draws the little blue one (and the pink one, Angel) as just about every other character from every other story you can possibly think of. (With an occasional visit from Toothless of How To Train Your Dragon, as well.) Visit his Etsy store, Stitchtoons, and see what he has to offer.

image c. 2019 by Jonathan Hallett

[Live] Jump Scare Apology

A deer guest joins us for a chunky roundup, lots of fun stories, plus a followup interview with Artconomy.

Link Roundup:- Furry anime: “Kemono Michi: Rise Up”

- Flayrah Review: Rukus

- Flop House podcast reviews Pottersville

- Kik says actually they aren’t shutting down

- Telegram SEC Crypto Currency Drama

- Telegram SEC Complaint

- Zyro and Maxwolf shown on news

- Furry invited into Judge Judy

- Bucky Badger comes out as a furry

- Onward Trailer

- UK’s first Chik-fil-a to close after only being open a week

- Moonlight: A Queer Werewolf Anthology

- Rawr_Jesse and KalCrux make silly halloween video

- Artconomy Giveaway Tweet

- Drunk_Wolves – “Long Email By Drunk_Wolves”

- Zimbe – “sample text here”

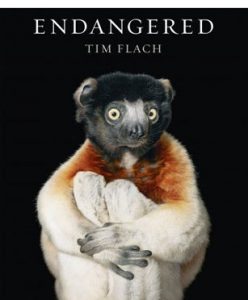

So Who’s In Danger?

Interesting news: Bob Weinstein, brother of the infamous-many-times-over Harvey, is still making movies… and his next project is animated. And furry, according to Animation World Network. “Bob Weinstein… is back on the scene with a new production company, Watch This Entertainment, according to The Hollywood Reporter. The new boutique production house’s first film is animated: Endangered, a family adventure being co-produced with Téa Leoni, who will also voice the lead character. The film is based on a 2017 book of animal photography by U.K. wildlife photographer Tim Flach. French collective Illogic, a group of six artists known for their work on the 2018 Oscar-nominated short film, Garden Party, will write and direct the film.” That’s all we know so far. Keep your ears up for when we learn more about the plot and the release date!

image c. 2019 Watch This Entertainment

Meow?

What do you mean he's adopted??? "This is Grace Yu Shu Wang's graduation thesis in Academy of Art University. The story is about a dog who thinks he is a cat, and meets a real dog for the first time. It took two and a half years from pre-production to fully rendered. Thanks to everyone who helped this project, and thank you for watching this movie!"

View Video

Murder: All Edge, No Cut — comic review by Enjy

Sometimes review books come here from outside of furry fandom. ‘Murder’ is a comic about an animal-rights antihero, where “animals mysteriously begin linking telepathically” and there’s a “powerful new plant-based badass”. It’s now in issue #2. “‘Murder’ takes readers into the darkest corners of animal agriculture, as one species at a time they begin to hear each other’s thoughts. Only one human, The Butcher’s Butcher, is able to hear their thoughts. As the animals revolt and the world’s food supply comes into jeopardy, the animal-rights activist is forced to decide between his vegan ethics and a world dependent on meat.”

Thanks to Enjy for big effort as always, check out her past writing, and remember we’re fiercely independent enough to be critical sometimes, but with hugs! – Patch

Murder is a comic created by the folks at Collab Creations (https://collabcreations.bigcartel.com/) which is billed as an “animal rights antihero” work centering on a vigilante activist and his wife, who fight to inflict the same pain on food company CEOs and ranchers as they inflict on animals ready for slaughter. It is written by Matthew Loisel with art created by Emiliano Correa, who also did work on the excellent Hexes series by Blue Fox Comics. We at DPP were given the first two issues for review.

The first thing you will do, when you open page one of Murder #1, will be laying eyes upon someone gassing an entire building of innocent people because they are working at a meat plant. In the next few pages, you’ll see something that’s meant to be taken seriously, but is unintentionally hilarious to the point where you have to read it over a few times to make sure there isn’t a joke being set up. The protagonist who just committed a literal war crime brutally murders a CEO with a steer, and then we’re led to believe this is the man we should be rooting for.

Unfortunately, The Butcher’s Butcher (a name with all the intricacy of pissing on an alley wall) doesn’t have nearly the level of charisma or likability or justification needed to be a believable anti-hero, even from a suspension of disbelief. What this comic is, no matter which side of the vegan vs. non vegan debate you are on, is soulless, one-dimensional propaganda with a “hero” that is much the same. It is like some bizarro universe where a Jack Chick tract has been transformed into weird murder-porn that seems more like the author’s personal fantasy than anything that could make a statement about the industry of food processing. The road most anti-heroes follow of doing the “right thing” the “wrong way” is completely tossed to the wayside here in favor of putting a camera behind that kid you knew in high school who had a Death Note that he wrote in.

After reading the first issue, I realized that I could not tackle this comic from a serious point of view, so I decided to give it the benefit of the doubt and take a look at it through a Silver-Age pulp lens. If you can get past the awful paneling with some of the most strangely placed speech bubbles, it almost takes on a so-bad-it’s-good quality, where you just want to see what crazy thing happens next, after you watch a dog and a cat play chess and have that “yes, but MY virtue” talk that you’ve seen in that exact setting a hundred times.

However in the second issue, it completely loses even that small bit of charm. In that issue we are introduced to The Butcher’s Butcher’s lover, who styles herself as “The Melanated Melody”.

Yeah, I know.

You are introduced to her as a person when a girl politely asks if she can sit next to her and she responds with dismissiveness, then texts her friend that “another yt girl just sat next 2 me” and “another yt girl about 2 call 911”. Why? Because the girl asked her why she was at a lecture for heat-resistant cows if she had a ranch in Wyoming as her lie stated. Yet another one-dimensional, single-issue cardboard cutout much like her lover, the Melanated Melody adds nothing to the story except for a sort of inside joke between the type of people who would enjoy these comics, yet another example of the author’s strange parading of myriad murderous fantasies and disguising it as an activism piece.

Where Murder could have succeeded was spending more time with the story of animals who can link telepathically, giving us a unique look at the meat industry that could also open the eyes of many people who are numb to its crimes. It seems the writer is building up to a story about how animals may rise up against us all. It could have shared more intricate workings of the industry instead of snippets of shock shots that would have mouths watering over at PETA. However, it is wasted away as a flimsy backdrop for the writer to task his characters with killing people he does not like, with a disturbing disregard for common sense or even the basest of justification.

What I hope Matthew Loisel realizes about the separation of villain and anti-hero is that your anti-hero needs to have a simple ingredient: personality. The characters we’re supposed to be rooting for in this comic are soulless weirdos who seem to revel more in killing others than they do in serving their cause. If you take the vegan newsletter out of the back of this comic, it turns into an issue of psychopaths on a rampage because they think they can hear animals. There’s no nuance here and no way to ascertain their goals unless you know where the writer is coming from politically and mentally.

This comic’s only saving grace is that the art and backgrounds are beautifully done, and Emiliano Correa really does the best he can with what he’s given here, showing off some interesting costume designs and great tonal work to set moods in scenes. Unfortunately, this isn’t enough to bring the comic anywhere near readable, relatable, or recommendable. I know what audience this comic is being written for, and I’m sure that they will enjoy being told what they like to hear. For the rest of the comic-reading world, who like to branch out and find stories layered underneath the bloodstains and hamfisted grandstanding, I suggest you give Murder a hard pass.

I give Murder a 3/10.

– Enjy

(Note from Patch:) I’m not immune to enjoying bloody horror, and this reminds me of a novel I read when it was a fresh debut with high cult notice: Cows, by Matthew Stokoe. It was a gory blast of B-movie splatterpunk and surrealism, with a put-upon loner who works in a slaughterhouse, starts to hear cows talk, and joins them.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

The British Bunnies are Back

Just today the trailers for the upcoming sequel to Peter Rabbit have hit the Internet. Peter Rabbit 2: The Runaway is coming to theaters next April, once again directed by Will Gluck. According to Wikipedia, “The film stars the voice of James Corden as the title character, with Rose Byrne, Domhnall Gleeson, Margot Robbie, Elizabeth Debicki, Daisy Ridley, and David Oyelowo also starring.” Meanwhile The Hollywood Reporter says, “The sequel to 2018’s Peter Rabbit catches up with Thomas, Bea and the rabbits that have become a makeshift family. Despite his best efforts, Peter can’t seem to shake his mischievous tendencies. When adventuring out of the garden, Peter finds himself in a world where his mischief is appreciated. Conflict ensues when his family risks everything to come looking for him, which forces Peter to figure out what kind of bunny he wants to be.” Check out the trailer for yourself.

image c. 2019 Sony Pictures

#223 - dEcEpTiOn! w/ Matthew Ebel, Fritzy, & Tigress @Furvana! - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1ICbhECEow for …

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1ICbhECEow for all things Dragget Show -- www.draggetshow.com support us on Patreon! -- www.patreon.com/thedraggetshow all of our audio podcasts at @the-dragget-show You can also find us on iTunes & wherever you find podcasts! Dragget Show telegram chat: telegram.me/draggetshow #223 - dEcEpTiOn! w/ Matthew Ebel, Fritzy, & Tigress @Furvana! - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u1ICbhECEow for …

Peter Rabbit 2: The Runaway

Should we have expected a sequel? Yes, I suppose we should have. Now we get to find out all the dark backstory to Peter's family and more crazy slapstick? I expect so. In PETER RABBIT™ 2: THE RUNAWAY, the lovable rogue is back. Bea, Thomas, and the rabbits have created a makeshift family, but despite his best efforts, Peter can't seem to shake his mischievous reputation. Adventuring out of the garden, Peter finds himself in a world where his mischief is appreciated, but when his family risks everything to come looking for him, Peter must figure out what kind of bunny he wants to be.

View Video

The Meerkats meet Shaun the Sheep

Well this is a weird crossover for today, we have the Compare the Market [1] meerkats (They're sort of a UK Geico Gecko) crossing over into the Aardman Shawn the Sheep universe because ... marketing. If you are not up on these mascots [2] here's an example of a typical Meerkat commercial: https://youtu.be/bhJm_94Nyt0 https://youtu.be/ukchs-Lzw3E [1] https://www.comparethemarket.com/ [2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Compare_the_Meerkat

View Video

Viva La Vida

A new fursuit video from Chatah Spots who is being extra cinematic in this outing. Fursuits and rock climbing looks amazing but that's something I rather watch on video then actually trying myself.

View Video

Trailer: Dolittle

I guess every decade or two we get another attempt at Doctor Dolittle only this time in the right period and with Robert Downey and here is hoping this is decent. I'm more down for that than say a gritty reboot in modern times. ...also I do like the tiger in this trailer ... "Hello lunch"

View Video

Murder: All Edge, No Cut

Murder: All Edge, No Cut