Feed aggregator

Lego: Rebuild The World

Running scared: an international zoosadism ring evades investigation.

Content warning for animal abuse and sexual violence. Part 2 of a 5 part update about the Zoosadist chat leaks.

In September 2018, the furry fandom was shocked by news about zoosadists (people into rape, torture and murder of animals for their fetish). Part 1) looks at how their ring was exposed, the threat to events, and who is implicated. A focus on ring member Tane makes a thread through a tangled story. This part looks at their evasion.

One excuse for people caught associated with the ring is downplaying it as “just fantasy”. To deflect public anger, member Kero the Wolf claimed he just likes “feral art” — a handful of pictures in a mountain of animal abuse in their chat leaks. Euphemistic illusions are a way to beg tolerance in a fandom where weird interests have free expression. But furries have limits. So the extreme fringe members hide their tracks with alt accounts, encryption and codes.

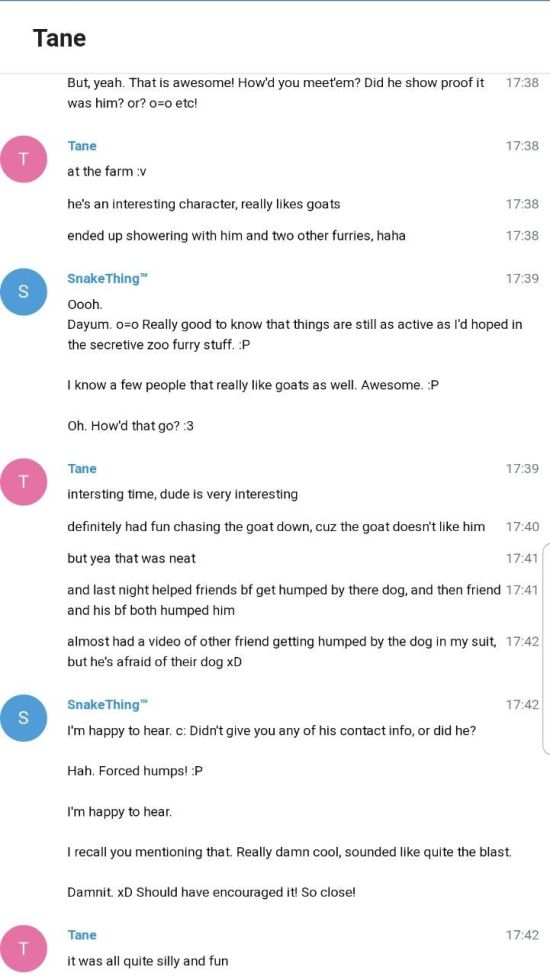

It’s the week after Halloween in 2017, and Tane was just at PAWcon, a small event in San Jose, CA. Snakething has frightening news — associates in the UK are being arrested for illegal content. Snakething is reassuring about Telegram’s encryption, but Tane is spooked about the arrest of ring associate Cupid (from Part 1). Cupid was arrested because Snakething leaked an incriminating video of him to a friend. The police took his phone — can they trace content on it to others? Will more dominos fall? The chatting is subdued for weeks after, and Snakething has to owe favors and settle fears. Notice “SC” (Telegram’s Secret Chat that deletes after viewing), and the code “RLC” (real life cub).

Police on the job [October 2018-now]

The envelope was sealed and mailed with tracking to see when it arrived. It was a moment of hope. A year after Tane’s chat about Cupid and “RLC”, higher powers now had a hard drive of leaked evidence. It included lots of work by furries to hold their hands and point out what to investigate.

The police don’t waste time on wild goose chases for internet rumors. So far, there have been 3 arrests for real activity that came from the leaks:

- SnakeThing (Levi Simmons) — arrested in Oregon for raping a puppy on video to share with the ring.

- EliteKnight (Christian Stewart Nichols) — arrested in Florida for abusing his dog on video to share with the ring.

- Woof (Ruben Pernas) — arrested in Cuba after a hunt to ID him for mutilating and killing animals for the ring.

Unfortunately (for now), Woof seems to be free because Cuba has no animal welfare laws. So the Cuban people hit the streets with public protest to ask their government for new laws because of him — an exceptional happening in a repressive country. There are claims that it’s the first officially-sanctioned, independently-organized, non government-associated protest in their nation’s history. I tried to get attention on the story with contacts at Vice and more, hoping that someone would cover a crime ring in furry fandom leaping to international notice. (A P.R. problem, or an opportunity to show what we care about?)

See Cuban protesters on the march below in a video about “Woof”.

[Zoosadist leaks] – Cuban media has exposed Rubén Marrero Pernas, AKA "Woof", perhaps the most extreme member of the zoosadist ring including @kerothewolf that was leaked in September.

"Cubans denounce a rapist and murderer of dogs." Article in Spanish:https://t.co/5AcaS6sHFv

— Dogpatch Press (@DogpatchPress) November 24, 2018

Underground in Cuba

On 8/26/19, I got a voice message about the video from an activist who helps Cuban animals to be adopted internationally with groups like CEDA. There are mixed up details in the section about who worked in Cuba (from 8:00-10:30). Even so, the activist was grateful to helpers for doing what they can.

After ID was found for Ruben Pernas, an underground effort had to be made to locate and expose him. Nobody would believe them for a long time (much like publishing stories about Kero and others) until they gathered backing and Pernas was fired from his job. CEDA didn’t approach the Cuban government, but they rescued his dogs. The story can’t be easily told, and I’m reminded of the film Citizen X (about a hunt for a killer complicated by Soviet police beaurocracy.)

The difficulty was manifold. The story could embarrass the system. Speaking about police in a country like Cuba can have consequences like denial of travel. There are no animal shelters in Cuba — it’s handled by individuals who take strays off the streets if they can, and groups like CEDA who try to get fosters, with help from Animal Protectors. Records must be hard to get. Their work had to be done in silence for 2 months, in collaboration with quiet middle-people.

“The hard part is keeping something so horrible without being able to discuss it… Let me tell you this was the most difficult and heartbreaking situation I’ve ever had to deal with. I want to shine the light on the good that Cuba did by the arrest.” — (Contact to the middle-people.)

Free speech to openly discuss this story is a freedom to cherish.

Limits of laws, and a problem for a community.

When the first sirens died down, Snakething was let go. The animal abuse hadn’t been found in time. Ring members including Woof are free to do more harm. But with the story out in public already, more attention can influence what happens next.

In furry fandom, talking on social media is one thing, but more focused work to get help can hit a wall. The Geek Social Fallacies lurk behind it. Backlash at “drama” means lazy insults to this volunteer for donating work that others don’t. Some say shut up and leave it to the cops, deferring to authority outside the community. You can find lots of balls in furry art, but where else? (Look at Cubans on the street protesting to their authorities for a change.)

I think the police don’t manage a community. They come after things go wrong, and they can’t just arrest people for saying things that we know they do:

- Animals don’t tell, while tech helps to cover up. (Corporations even profit from animal cruelty media they won’t regulate.)

- Local police have low priority for cybercrime out of their area. Federals have bigger fish to fry (terrorism etc.), so animal abuse falls back to local police.

- Outdated laws didn’t envision a ring like this, which skips jurisdictions, while bestiality isn’t illegal everywhere or regulated like child abuse. Videos circulate for years, but statutory limits make short times to solve crimes. The police may not waste effort if arresting ends up in dropped charges.

These limits blocked a New York police investigation into Kero the Wolf. His parents stonewalled them from comparing evidence of crime on their property (in a garage and campers) that was in abuse videos and Kero’s Beastforum posts. The statutory time limits ran out. Investigation continues in PA.

The chat logs of the zoosadist ring discuss this, one tactic to get away with crime is using a fursuit and concealing face. In kero's case they have his garage in an abuse vid and one he posted himself, but it takes a warrant to make it courtworthy. No face = no warrant, catch22

— Dogpatch Press (@DogpatchPress) August 21, 2019

I've spent the last two weeks looking over the evidence that had been given to the New York police investigating Kero The Wolf. ITT I explain why there's hard proof the statute of limitations is what hamstrung NY's case against Kero, and how he's gotten away on a technicality.

— Archive The Wolf (@KeroArchive) September 2, 2019

Only police may have certain power, but only insiders (or family) may be able to help them to use it. Detective work can take years, and a few arrests may not stop a ring. People like OJ Simpson get off charges (but not from personal, community or civil judgement). Interfering with police is a concern, but leaving it only to them can be negligent. Shining a light matters when predators prey in the shadows. There’s no “witch hunt” for witches right next to you.

Running scared [September 2018]

Back to the fandom impact right when the leaks reached the public. I had to guess why lots of people were coming out of the woodwork in my messages with weird intentions. What do you think is going on when I get contacted unprompted, about people I don’t know, to deny things I didn’t bring up? It gives a strong impression of fear and coverup of many wider ties. I heard from:

- Kero the Wolf — Told me his excuse about being hacked. It was unbelievable and I told him to stop, get a lawyer and go dark. Kero eventually admitted that he did lie to me and thousands of fans with a downloaded screenshot of “hacker” activity that he told me came from his device. But he still wanted it both ways as if mystery hackers wrote the bad messages in his name, and he only wrote a small part that couldn’t get him in much trouble.

- Saito Fox — Contacted me on behalf of Kero with the same story (and fake screenshot) at nearly the same time. He was very close to RC Fox (who killed himself on the day he was facing conviction for child porn charges,) according to RC Fox’s friend Pakyto who traded zoosadist porn with Snakething. Saito turned up in the logs for running a zoophile group for Midwest Furfest, where Snakething tried to hook them up with animal owners. What a tangle.

- Defenders and friends of people in the ring — some with fandom popularity — threw fits when I wouldn’t buy the hacking excuse, or wanted to debate that zoophiles being underground are like gays forced to meet in secret in the 1950’s (a reminder of gay rights dissociating from a fringe of pedophiles trying to ride their coattails.) They were clearly whispering in angry private circles because I got tagged into this.

- Leko — a local furry who I knew in person (and didn’t know was a partner of Tane) started a new thread to follow.

A cover story, and authenticating the logs

Tane’s partner tells a story that isn’t consistent with the chat logs and other corroborating details.

- Telegram channel: Leko’s messages about Tane.

Leko claims that Tane was in the ring to set the other person up for the police, but there wasn’t enough evidence to make a case. Leko says he isn’t one of those “demented perverts”, just a normal one (so it’s just fantasy, but the chats are real?) The chats are excused for having no illegal content, only commonly available files — but it doesn’t explain all the file removals from Tane’s logs, and something even more inconsistent.

Files in the chat leaks DID cause arrests. There was no help from Tane, according to the leakers, and he failed to report evidence. In 2017, when Tane received Snakething’s 2016 puppy rape video, it wouldn’t have been too late to get him charged. Holding it let the statutory time limits decay until he got away with it in 2018. (Leko sent the claims before Snakething’s arrest made them inconsistent.)

Kero claimed to be targeted by hackers. Woof confessed and EliteKnight confirmed. Glowfox claimed the logs were “out of context”. Tane claimed a self-made police sting (supported by nothing else.) The stories didn’t line up or win benefit of the doubt for anyone. At least Tane’s is based on the logs being real.

Second corroboration

I went beyond Leko’s claims to corroborate the Telegram logs. When the chats leaked, Tane locked his Twitter and switched usernames with another account. But first, a source with access provided a screenshot dump of the timeline. I painstakingly traced how his Tweets synched with his private messages.

- Telegram channel: Tane’s Twitter and chat comparison (18 points corroborating the logs).

Both sources have info the other doesn’t, such as photos matching text, and location info original to the Telegram logs that couldn’t be seen in public posts. Other Twitter accounts only tie in by roundabout research (such as tracing user location) that won’t make sense if simply faked in text, showing one source isn’t just based on the other. They weave together at points like this one, from Tane’s trip to a zoophile meet on a farm in Nebraska.

Triple check: Why wasn’t even more evidence brought to the police?

Leko claimed Tane was in the chats, but didn’t have enough evidence to go to police. (Part 4 will link a detailed breakdown of the chats with over 650 screenshots.)

But Tane received original videos of animal abuse from Snakething. He claimed to do animal sex tourism and helped hook up other ring members. Explained how to drug (roofie) drinks at cons. Targeted Nachodoggo for rape, and was told of a plan to molest a child. Didn’t seek ID to help targets in danger, and used Secret Chat to hide evidence at his request. THIS was a “setup?”

I still went out of the way to check. Leko had said they were preparing a statement together to own up to some things and explain the police claims. In September 2019, I got in touch before publishing, and offered an opportunity to clear things up and give their side, like Tane offered on his Twitter. I sent questions:

I still went out of the way to check. Leko had said they were preparing a statement together to own up to some things and explain the police claims. In September 2019, I got in touch before publishing, and offered an opportunity to clear things up and give their side, like Tane offered on his Twitter. I sent questions:

- What records were gathered for reporting to police?

- Why wasn’t it enough evidence to give them?

- How did Tane gather records when he asked to use Secret Chat?

- Is he willing to explain the details of specific plans and files that were traded and discussed?

- Is he willing to ID specific places and people named in the chats? Will any of them back this up?

- What effort was made to get ID for cases of imminent harm?

- How did he cooperate in the arrests of Levi Simmons, Christian Nichols, and Ruben Pernas (Snakething, Eliteknight, and Woof)? Will anyone back this up?

- Will he do a video interview?

There was no reply by publishing time. I look forward to more info. Until then, the logs can speak for themselves. They’re very informative for how Tane fit in the ring and how it worked. From not even knowing who he was at first — and even being asked for favors about him — I had a fresh start to investigate without personal bias, and every detail I found matches this report.

A job for a team of one [October 2018]

The story until now has looked at who was in the ring, the limits for police, confusion and dodging, and the horrifying content instead of euphemistic “fantasy”. Then there was a big job to sort info for further action. It needed a team, so I gathered a small one. Members read Tane’s logs and reacted:

Tane’s awful. He talked for 15 HTML files. And he’s on the list of people into real life cub…’with experience’. There’s no images… because Tane’s an infosec guy. He moves to secret chat a number of times. It’s hard to summarize all of the terrible things Tane does/says. None of this is “He’s sorry for what he’s done and is seeking therapy and professional help to stop the behavior entirely.” Just “Please bury his guilt so we can keep doing what we’re doing without anyone knowing or confronting us”… There’s no fucking way he needed to prove (Snakething)’s guilt for that long. If he was attempting to play undercover cop, he went about it in the worst possible way… and never actually did anything with the info.

Like, if he wants to play that angle, he’d better have receipts of actually talking to police. The undercover cop story sounds about as believable as the being hacked story… an actual agent wouldn’t send messages on a self-destruct timer. Because it’d make their case a lot harder to prove. And Tane was the one who pushed that, not (Snakething). Any mole wants info to be as archived as long as possible. Tane actively took steps to do the opposite.

Other groups gathered and were infested by trolls, moles and misinformation, making it a minefield to work with others. It needed full time staff, but that doesn’t exist in fandom. Detaching from agendas meant doing it alone. Without more resources, it’s taken a year to investigate and report more.

Complicity by silence

A lot of the community would rather “see no evil” than know more. The path of least resistance would be shutting up and letting someone else do it… maybe nobody, while we wait for help that never comes.

That’s how the ring members hope it goes. But it was very odd to have this fall out of the sky, then have scared people bring up issues I didn’t start, about people I didn’t know, and hope I wouldn’t talk. The more I looked, the more it was clear that sitting back would clear a path for manipulation and complicity.

That pressure even came from higher powers in the community — some of them afraid about their own ties. More about that in Part 3.

More — Part 1): Exposing the ring. Part 2): Running scared. Part 3): Investigation blocked. Part 4): A new development. Part 5): Interview with an expert.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

A Florida Fur’s Guide to Beating the Heat

Midwest FurFest bans Milo Yiannopoulos from con attendance

KFC: What The Cluck?!

Just your typical people turning into Chickens to advertise KFC commercial. (I think we need some fursuit films that animate expressions like this)

View Video

TigerTails Radio Season 12 Episode 01

Evidence of a furry crime ring emerges: Legal docs and news tie Cupid, Tane, more to zoosadism.

Content warning for animal abuse and sexual violence. Part 1 of a 5 part update about the Zoosadist chat leaks.

A rape plan [October 2017]

It’s near Halloween. In Coos Bay, Oregon, spooky movies are playing at the Egyptian Theater. And Snakething (Levi Simmons) is at home having an evening chat with a new friend, Tane, a furry fan in California. The men were introduced by a friend with a mutual interest.

Tane goes to college, and Snakething lives with his mom — he can’t drive or work, so he spends time gathering online friends from around the world. Most come from the furry fandom. Furries often gather for special interests, like art or music, but Snakething obsessively collects porn from secret sources. His friends make a crime ring for zoosadism (a fetish for raping, torturing and murdering animals). They call it “hardzoo” (or hardzoosuiting with a fursuit, a very rare interest that they try to “corrupt” others into).

Tonight Tane and Snakething are making plans for Nacho (Nachodoggo), a woman who recently reported crimes by two other men tied to the ring. (A video of those men abusing her dog was leaked by a friend of Snakething, leading to their arrests.) The plan is to drug Nachodoggo, and when she’s unconscious, rape her with others she isn’t aware of, like their friend Tekkita.

Since they met, Tane has enjoyed a video where Snakething drugged and raped a 10-12 week old puppy. The puppy came from Craigslist, and may have been killed and dumped by the camera man to hide it. (Snakething claims it’s OK but doesn’t know.) The video was made to share with the ring. Members gain trust and favors by hooking each other up with people, animals, or content for trade, where the worst is rarest, as if the victims are Pokemon cards for kids to collect. They have a term for child targets: RLC (real life cub).

The furry fandom has maybe a million members in the world. Few or none know the full extent of one of the worst stories that has ever happened inside it. The zoosadists are a tiny group hiding in a fringe of a subculture, but one germ can take down a giant. Let’s put it under a microscope.

A threat to events [Now]

The plan to rape Nachodoggo was still secret when I saw the crimes she reported in Seattle news. In 2017, I contacted her to learn about the arrests of “Noodles” and “Cupid” (Kevin Richards and Matthew Grabowski) in Renton, WA. But when the ringleader Snakething was arrested in October 2018 for the puppy rape, he escaped charges due to statutory limits. (Time wouldn’t run out so fast for a human victim.) There are clues that much more was hidden from the police.

Tane, Cupid, and other ring members are still active at furry events. Event organizers know it.

Their plan is leading this story to highlight an active threat. Nachodoggo told me: “these men are dangerous“. She says the screenshots I showed her are real plans by people who would do anything to get what they want, with associates already using drugging and deception for sex crime.

I spoke to people involved and learned undisclosed details. Nachodoggo faced extortion and backlash, and her ID was redacted in the crime charges due to threats. There may be more interference like that, but as a source, the police found her reports worthy for cases that cleared with convictions in April 2019.

Those linked legal docs are the tip of the iceberg. Others won’t tell, and animals can’t, but a lot can be said about people known to be involved. Some claim innocence or say it’s fantasy talk. Snakething’s arrest — and this report — shows that people are getting away with crime even when caught red handed.

Data points of a larger ring: Cupid and Noodles in the news, months after abusing Nachodoggo’s dog and weeks after a plan to rape her with Cupid’s friend Tekkita.

Back at events right after conviction in 2019.

An international problem

While the crimes reported by Nachodoggo were in process, I had no idea about a much larger story brewing in secret. Members of the zoosadist ring were being introduced through a darkweb forum called Animals Dark Paradise that was for cruelty on the level of urban legends. I’d never heard of real animal snuff porn (where victims are used for sex during or after being killed), let alone enough demand for group meetings to make it.

Less extreme bestiality content has long thrived on unregulated sites like Beastforum. When it closed in February 2019, the Washington Examiner quoted an activist who called it a sign of legislation in progress for “a national policy against bestiality”. Meanwhile in the UK, the BBC News reported about trading of abuse images. It’s being displaced from the open web, to the dark web, to encrypted messaging:

Secure messaging apps, including Telegram and Discord, have become popular following successful police operations against criminal markets operating on what is known as the dark web… Messages are protected by peer-to-peer encryption, generally putting them beyond law enforcement’s reach.

UPDATE: shortly after this report was published, the NY Times reported an exponential rise of abuse image trading on the internet. Over 1/3 of reports to law enforcement ever received were made in the last year. It shows law enforcement resources being dwarfed by the scale, extremity, and enterprising complexity of the problem. This story would be a symptom of that explosion of tech-enabled abuse.

A ring exposed [September 2018]

On Telegram, Snakething’s “hardzoo” group (“The Forest” or “BBB/Beasty Beast Beasts”) filtered in members from larger zoophile groups, letting them concentrate resources and contacts. Unsatisfied by trading common files, they gathered to create zoosadist content that resembled the acts of movie serial killers.

Dogs would be gotten from animal rescues or private ads from people hoping to give them forever homes. They would be restrained with duct tape, rope or drugs, then mutilated and torn apart to hear them “sing”, in the words of a ring member who was arrested for killings in Cuba.

We can now read that Snakething and Tane were planning to rent a beautiful cabin in the woods for a weekend getaway, like a group vacation for five normal friends. But instead of a place to enjoy a fire or go hiking, they wanted to budget for “toys” (disposable animals from Craigslist), and looked for seclusion so screaming dogs couldn’t be heard being raped.

The rental site where they looked at cabins in Mt. Hood National Forest, Oregon. The plan could use Tane’s experience in 4-wheeler driving, and video tech skills for setting up furry cons.

This upset admins of shady groups like Zoofurries Society/Zeta Corner or Zoofurries Alliance. They got a password that Snakething gave to a play partner, and dumped the logs from his Telegram account. On 9/16/2018, they put it on Twitter and tagged me as a news source, but I had no idea what it was about.

Reasons to leak

The leakers claimed “no vendettas”. I started with a theory of fallout from the Nachodoggo/Cupid/Noodles cases, with dueling evidence disclosures tied to plea deals (or “insurance” from a dead man’s switch). Or a move to taint evidence to block more charges. There were deals, revenge motives and friend ties, but I couldn’t say they directly caused the leaks or had anything to do with why many members were exposed.

The going story says a domination/blackmail fetish game was used to trick a password out of Snakething’s play partner, and then truly expose animal torture. The partner seems to be EliteKnight, who posted a story to match. He was a definite candidate for blackmail about illegal activity. (And being a “fall guy”. I think they have others being visible faces for their groups to dump if they’re at risk, too.)

Leaking online instead of reporting to police made a mess for investigation. I think the leakers did it because they feared being arrested, exposing friends and losing their groups. It was extremely dubious to see them pose as having good intentions for cutting risks to themselves. (Snakething became a security threat to them when his video trading caused Cupid’s arrest). There’s many reasons to find this unacceptable and a form of obstruction. It’s also likely that the story wouldn’t be known otherwise.

I doubt any single person knows how deep this goes, but after hundreds of hours of research and talking to dozens of sources, I can say more than anyone has written in one place so far.

Reporting the story [One year later]

This multi-part article took weeks to write, including sorting evidence in linked archives. This is a third news update since 2018. Furry readers may have heard of Kero the Wolf, the highest-profile gateway to the story. (Kero’s boyfriend was Illone/Colwyn, a fellow zoosadist known as very active on Animals Dark Paradise). Kero’s 100K-strong Youtube following (and lying to the public, including hiding ties to “Colwyn”) earned a focus for previous articles:

- Zoosadism leaks: possibly the worst story to ever hit fandom

- Zoosadism investigation: Capitalizing on abuse, and the ugly persistence of Kero.

This is the hardest story I’ve written, by research time, emotional cost and backlash. That includes knee-jerk attacks from bystanders about dealing with sources or trying to get help. The cost is more than could ever be gained, but it comes from caring about others. I hate having it in news about furries, but I hate having it buried even more.

In a year of trying to shine light on a murky story, I can see how tangled it is. Ring members got caught up with infighting, infiltrating, bargaining, and blackmailing each other. Zoophiles that partially outed them threaten to ruin the story if they can’t control it. They want apologism and credit for helping (imagine a necrophile, leaning on a shovel, saying “we don’t like people who kill for corpses”). Sources or reporters are targets of smokescreens, manipulation, and backlash to limit exposure. Community apathy includes denying it’s a fandom issue, acting like it’s private business, just fantasy, “drama”, or cyber-bullying to talk about it. Everyone acts like a ring isn’t a ring.

Worst of all are blind complicity, defenses for indefensible things, and lies about the story being fake.

The chats are real people talking about real activity.

See for yourself. Warning: graphic evidence of animal abuse. Check legality in your jurisdiction to view this. To my knowledge (not a lawyer), viewing to investigate in the USA is legal and it’s been checked by many people. It may be illegal in the UK and Crown dependencies under the “extreme porn” laws. [TEMPORARILY DOWN FOR NEW POLICE REPORT]

Members of the ring confirm the logs are real by their actions. Their private activity cross-checks with years of matching activity with friends, social media posts, news reports, and crime cases. It synchs with original information like incriminating photos/videos found only in the logs. One purpose for the ring was to hook each other up to make “zoosuiter” porn, and unique costumes can identify their wearers. With Kero’s boyfriend Illone/Colwyn, his death (by heroin) ties many pieces together (that’s why Kero erases the memory of his dead boyfriend, who can never speak denial.) It all weaves a huge matrix of corroboration.

For a conspiracy theory of faking the chats, it would take a squad of Hollywood scriptwriters, with intimate knowledge of hundreds of ID’s and movements that would need a time machine to predict, somehow having power over uneditable server-side sources. A claim about evidence of hacking was shown to be a lie by Kero (who still hasn’t fully disclosed his involvement). Hacking Telegram to target one member and smear their image would be akin to a government taking down another country’s electrical grid to turn off one light bulb; faking a giant ring is absurdly unreal for such a motive. This mess of a conspiracy theory would be hopeless to carry out undetected, with no coherent reason, and if one could hack Telegram they could claim huge rewards. I haven’t seen a single real clue that anything was faked — although not everything was exposed that could be.

The cult of cruelty

Known members exposed in the ring (by account names):

- Snakething — Ringleader in Oregon and obsessive collector of extreme porn, who gathered members on Telegram to feed his urges.

- Woof — Cuban, basically an animal serial killer to make torture porn, and focus of a hunt that extracted a confession.

- Eliteknight — Florida resident and play partner of Snakething, who abused his dog for zoosadist porn. He posted confirmation for the leaks.

- Glowfox — Peruvian who forced sadism on dogs, whose boyfriend appears in the logs too. He claimed to be taken “out of context” for being in the ring.

- Tane — Had a special porn trading deal with Snakething. Partner to an SF Bay Area furry, who confirmed Tane was in the ring with excuses about why.

- Kero — From PA, he made necro/bestiality content behind the scenes while doing innocent-looking fursuiting on Youtube for over 100,000 subscribers.

- Sephius — Austrian who claimed to rape puppies to death, thought to be the person in a video of sex with a dead deer originally attributed to Kero.

- Equinas — Zoophile ranch owner in WA, hoster of furry/zoophile parties and Calzoo ring activity going back to the 1990’s.

- Tim Win/Matepups — Camera man for Snakething’s abuse video, associate of Equinas, reputed to be the most unhinged member with many victims.

- Tekkita/Mr. Bitchtits — Zoosadist contact of Snakething, associated to Cupid and source for porn of him (possible partner or roommate).

- Techno Husky — SF Bay Area zoosadist who Snakething tries to convince to abuse the family chihuahua, text indicates sharing child porn.

- Sangie — play partner of Snakething, owner of Inkedfur (a furry art printing company), helps groom the nephew of Snakething for molesting.

- Blonde Dog/Golden Retriever — Into decapitation and necrophilia with puppies, works at a dog boarding kennel, meets Tane in person.

- Ember — Ring member who discussed sedating dogs for rape, who caught public attention for his drug overdose at BLFC 2017.

- Kintari — Previously known vet tech/zoophile (NSFW) named in the logs for zoosadism/snuff porn, and source for drugs to subdue animals for rape.

- Illone Sheppypaws — Kero’s boyfriend, Animals Dark Paradise user who introduced Woof to Snakething.

- Coywolf, Humacyrnus, Mo Mo, Shepnuts, Zeta Omega, Xyro, Miskas, and more who aren’t named.

Associated by guilt

Dozens of members make countless ties to already known crime:

- Sangie is a convicted sex offender (and subject of many tips to this site about a repeat pattern).

- Spark Dalmation is a repeat sex offender. In the chat he’s on a list of names, including Tane, said to be into/experienced with “RLC” (Real Life Cub.)

- Icepaws was a former Anthrocon staffer whose porn is shared by Snakething, arrested for animal abuse in the bust of a furry pedophile ring in PA.

- Cupid and Noodles were convicted for their charges, with court records corroborating what’s in the logs.

Association — in the court record of Cupid’s conviction. It has Nachodoggo’s 2017 police report with details that appeared independently in the 2018 chat leaks, like Cupid getting animals from private adoption ads to rape and dump. Tane’s logs mention that while Cupid was on bail and unable to own pets, there was a plan to pay for delivery of “one time use” animals from Craigslist, which would be snuffed and left in the woods. Some members discussed large payments to make videos. These are some of many corroborating details between people, legal docs, and media.

Known leakers and hosts

Difficult sourcing may be the only way this could be seen:

- Shadowwoof (leaker) — Admin of groups like Zoofurries Society (with around 1000 members and at one time had admins like zoosadist Tekkita). He’s been admin/opposition for Simba in the UK (known for running a furry Discord group with a cult-like/multi-level social credit system. Simba collects user info and runs FinDom groups, and is under police investigation.) Shadow uses threats/blackmail to gather info, so wasn’t consulted for this article.

- Akela (leaker) — member of zoophile groups. He uses threats/blackmail to gather info, so wasn’t consulted for this article.

- Logs are hosted on TOR by Doug Spink (not a source). He plays “zoophile media spokesperson,” with a cocaine-smuggling felony record, news articles and a book by a journalist about him. He posted that ring members force the logs down from hosts with legal claims that their own info is too extreme.

- Logs are also on Kiwifarms, a notorious harassment site that rejects takedowns to be one of the only open hosts.

Demanding other sourcing is an easy deflection. (Where else would it come from? How does Wikileaks get documents?) Deniers can find lots of ways to attack this messenger, because that’s easier than defending a ring. It’s a common tactic to cover up institutional abuse, although a fandom doesn’t exactly have institutions. There’s more like a little power and lots of “not my job” involved. Nobody has a real watchdog job in it (I’m a volunteer who just reports things).

Independently of getting involved with the leakers, I looked myself and found a real story. It made much harder work for a lone reporter, vastly uncompensated by tiny PBS-style support. It lets me say my article has no profit, and no stake in blackmail, harassment sites, deals, or protecting anyone. Again, not one real clue of faking has reached my attention, and the logs have a mountain of corroboration. It’s getting stronger over time with elements like Cupid’s conviction.

A major news report of orphanage abuse by nuns lacked institutional records that exposed priest abuse — instead it cross-checked many sources to build evidence.

One ring to rule them all

The zoosadist ring has abuse beyond any seen in the past, but it ties to an overlapping list of older rings:

- Calzoo (started in the 1990’s), whose members “have turned up in nearly every furry zoophile incident of note” (including this one.)

- The Enumclaw ring, known in headlines and a documentary about a “bestiality brothel,” sex tourism and the horse sex death of “Mr. Hands” (Kenneth Pinyan, an employee of Boeing). I found a tie to a Zoofurries Society admin.

- The Dolph ring, an animal sex tourism group at a Swiss waterpark that shut down after dolphins died from poor care.

- The PA pedophile ring of Rebelwolf, which made news with 8 arrests in 2016.

There were enough ties that I had already been comparing news stories and developing sources before learning of the zoosadist ring in 2018. It took root in furry zoophile groups, and wormed into a niche of a niche of a subculture using its resources and networks. These sub-groups are sometimes held out as social connection for people who love their pets that much, but are founded on porn trading with mental gymnastics about it. (They’re also places where members may be surveilled or blackmailed.) Keep in mind that nobody approves who joins the community, and furry fans are also working to uncover the story.

Focus on Tane

One ring member has gotten low notice so far for high activity. His chat logs with the ringleader Snakething are some of the longest, and they had a deal for sharing all content that came in. (Only one other person had such access.) Later parts will show triple-checked corroboration that Tane’s logs are real, and a detailed breakdown of the contents (including practices to evade police.) It makes a thread to help follow a tangled story where tech has a big role.

Tane works in information security with government clearance, and was known as a member of the public DEFCON Furs group and a regular attendee of the DEF CON hacker convention in Las Vegas. (See their official statement below.) DEFCON Furs is a tech focused group “for members of the infosec community that share an interest in the furry fandom,” and they organize events and parties at the con. Tane appeared in a Vice article about fursuiting at DEF CON. He seems to travel a lot, which ties to animal sex tourism clues in the logs, including going to a zoophile meet at a farm in Nebraska.

At the Nebraska farm, Tane met a friend who runs a furry porn imageboard, and a performer in animal porn videos from the commercial maker Petlust. (An employee did a Q&A about his job there, mentioning “tech savvy” and a tie to the “Mr. Hands” incident.)

These screens came from Tane’s Howlr profile. Notice how many furry events are on his list — places where ring members planned to meet for their activity.

Howlr is a popular furry sex hookup service like Grindr, generally for consenting adults, but founded by Stormy, who left due to controversy about bestiality acts shortly before the chat leaks. Independently, the leaks tied him to the ring’s plans for “zoosuiter” parties with pimp-like animal owner hookups at furry cons.

Monsters with friendly faces

Old horror stories have monsters who lurk in the wilderness beyond civilization. Modern monsters hide behind masks of technology, but walk among you like friends. They aren’t just strangers on the internet. Some of them help to run your community while complicit with this story. That’s everyone’s problem.

Come back for more about that in the next parts. As always, send requests for help to report anonymously, guest submissions, hugs, coupons, death threats, or (worst of all) plans to call me a narc and throw gum on my fursuit to: patch.ofurr@gmail.com.

UPDATES and corrections: Cupid did not work for Boeing, he worked at SEA-TAC as a service engineer for Alaska Airlines. EliteKnight was not in Ohio (source of a police report about him,) he was in Florida. Miskas is added to names in the ring from the chat logs and a tip from a source whose own experience corroborates the logs. “Nacho” has been updated to account name “Nachodoggo” to help separate it from others with similar handles.

On 9/17/19, organizers reached out with an official statement: “DEFCON Furs does not tolerate abusive behavior. Actions have been taken to address the accusations raised by this article.” From more personal messages with DEFCON Furs members, at this time I would think Tane’s activity was never condoned and doesn’t represent them. It only shows another member of the public being interested in tech. Positive activities they organize deserve an article of their own.

More — Part 1): Exposing the ring. Part 2): Running scared. Part 3): Investigation blocked. Part 4): A new development. Part 5): Interview with an expert.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

From The Outside to the Centaur

Ow… Hey! It’s crazy-hot out. But we’re back with more anthropomorphic news. We got this from Animation Scoop: “Netflix will transport viewers around the world to a colorful and imaginative land where fantastical creatures sing and adventure surrounds you – welcome to Centaurworld. The new kids animated series hails from first-time showrunner Megan Nicole Dong, a 2017 honoree of Variety’s “10 Animators to Watch” list… Centaurworld follows a war horse who is transported from her embattled world to a strange land inhabited by silly, singing centaurs of all species, shapes, and sizes. Desperate to return home, she befriends a group of these magical creatures and embarks on a journey that will test her more than any battle she’s ever faced before… The series will feature a mix of animation styles and each episode will include original songs in a variety of genres.” No word yet on a premier date, but it’s Netflix — they will let us know!

image c. 2019 Netflix

Supporting my Local Furry Con

GFTV releases 2 new channels

Today, the GFTV has released 2 new channels as a rebrand for our existing international and Mainland Chinese channel. With that, meet our channels, Ch. 1 (International) and Ch. 2 (China)! With this new release, all of our English programmes will go under Ch. 1, whereas our Chinese programmes would go under Ch. 2. Bilingual […]

[Live] Tailnadoes

A smol roundup followed by casual convo.

Link Roundup:- Anthro NE will get a new charity

- Furries Are Arguing About Whether They Should Support Police Dog Charities

- Tails and Tornadoes Fur Con raises $7000 for wildlife rescue

- Casual Mention of Furries

- How to stop DHGate

- VancouFur opens rooms tomorrow

- CRISPR Gene-Editing May Offer Path To Cure For HIV, First Published Report Shows

- BBF’s Anthrocon Preview

- Cops shut down massive 3,000-person game of hide-and-seek at Ikea

- ‘Storm Area 51’ Founder Pulls Out Of ‘Alien Stock,’ Fears Another Fyre Festival

The Ultimate ”Bambi” Recap

Seems accurate, If you have not seen his lion king recap here is that as well: https://youtu.be/Bge_9DsoMWI

View Video

Trailer: You Son of a Bitch!

Check out the trailer for this adult animated furry rom-com from Philippines-based studio Rocketsheep that's getting a release in 2020. Now I realize the world needs more furry adult romantic-comedies. You can see more on their Facebook page Nimfa Dimaano [1]. [1] https://www.facebook.com/MissNimfa

View Video

Meet Alf Doggo, Chilean furry artist for the new site banner.

If you like this interview, read The Diversity of the Latin American Furry Fandom – by Rama and Patch. Thanks to a special Cat for translating from Spanish.

(Patch:) Hi Alf! Very nice art, drawing backgrounds can be hard work besides the characters. The site is commissioning regular new banners and featuring the artists, with interest in lesser-known artists in the world outside of American fandom. The last one featured was Meru Tenshi from the Phillipines. Can you tell me about where you live, and say a little more about yourself?

I’m from Chile, from the city Iquique. I spent part of my childhood in ‘Lana’, a small town in the interior of Combarbalá, Ovalle. That’s where my grandma lives, she’s a farmer. (She has no livestock, only agriculture.)

Do you mostly do art in furry fandom, or somewhere else like for studying at school or publishing for non furries?

I have always spent my time drawing whatever I like. It’s like phases. I started in a church, and I did oil and acrylic, it was pretty realistic. After that I turned into an Otaku, drawing a lot of anime. Now I’m only furry, and for my career I only do architectural drawing.

Want to share your links on social media?

I’m not very active in my social networks, because of school, but here they are.

How did you find furry, and what’s the fandom like where you live?

I found the fandom with one friend from University, while we talk about crazy things. She told me about this group and I got very curious. In August 2017 I got into the fandom.

It was interesting to hear about your family and grandma, it makes me wonder, is it unusual to be an artist in your family or where you grew up?

No. In my grandma’s house we didn’t have too many things to do, there wasn’t electricity. Besides playing outside, there wasn’t much to do. We spent the time drawing, or playing with mud, or learning to play a musical instrument. I got involved in drawing. Never managed to get the musical ear from my mother. My sister did, she played the whole day. Meanwhile, I drew the whole day.

My grandmother is dedicated to agricultural work, mainly to Peach Huesillo. But she also has fig trees, parronales* and much more… I drew under the trees and watched the animals pass, mainly the dogs and grazing goats.

When I wasn’t drawing, I would go to a river nearby. I built wired things… it was my imagination going crazy. I built my own version of a futbol (soccer) table. And built time machines… I even saddled and mounted a sheep. I was only calm when drawing.

When I wasn’t drawing, I would go to a river nearby. I built wired things… it was my imagination going crazy. I built my own version of a futbol (soccer) table. And built time machines… I even saddled and mounted a sheep. I was only calm when drawing.

All my family does art in many ways, starting from musicians to sculptors, painters, bakers, etc. My generation was not so good, but still keeps the love for the art.

And just to be clear, right now my grandma has electricity and there is even open television. It’s a rural place and the technology comes slowly.

*[I had to look up Parronales… it’s large scale grape farming, with labor that can be split by gender in Chile. – Patch]

Do you spend time with other furries in Chile, and what do you do? Or is it mostly on the internet?

Do you spend time with other furries in Chile, and what do you do? Or is it mostly on the internet?

Mainly on the internet. I don’t know other furs in Iquique, my city.

Do you have any favorite furry characters, whether in game or movies or tv — or ones made up by you or artists you like?

Balto!

Can you compare the fandom in North America to the part where you are? Do you hear about it a lot, or do you mostly talk about happenings closer to home?

I have no point of measurement about how the fandom is in US. Only things that I’ve seen of Mexico on the internet. From South America? Nothing… In Iquique there are no furry events, not even another furry from my same city.

The art you did for the site is super cute. Is there one thing you could say about it, like what you used for reference, or what style you used?

For the buildings in the drawing I just used to two vanishing points. I used simple elements, no references. I think I just used my head and anything that came out from my memory. For the bus I checked internet pictures. I used pictures for you sent by Mr. Cat. For the rest of the characters, I was asked to not use ‘known’ furs, so I invented all of them generic (a cat with stripes, a fox, a couple of bunnies, a panda, a black cat, a wolf, a pig, etc.)

Do you have any favorite art you drew that you want shared?

This commission is very important for me. It was requested from a Mexican artist called ‘Paco Panda‘. I did it with a simple mouse (I didn’t have a digitizing tablet at that time) and I opened commissions to buy one. But drawing with a mouse was painful (like a real physical pain) and I was going to decline. But Paco paid me for this drawing and give me a huge tip, that was a boost to buy the tablet that I have now. I’m very grateful to him.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

A chat with Brazil FurFest

When I initially contacted BFF to ask about their recent sponsorship agreement I thought that was it. Then my fellow US colleague Rosca Santigria sent 3 questions: What is your response/feelings about the Brazil Amazon Rainforest fire? There is a lot of public outrage about it in Mexico, USA, and Canada. Are there any efforts […]

The “New Paws” Hoax: How alt-right trolls piled on a disabled man to boost their failing careers.

4chan started a conspiracy theory that PretzelCollie used dry ice on his hands because he wanted them to be amputated and replaced with paws.

Hands-down one of the most depraved harassment campaigns I've ever seen. And it's of course blatantly untrue too. https://t.co/rC2pzgITL1

— Mythic (@MythicalRedFox) August 31, 2019

A shocking accident.

In 2015 I met a furry who joined furmeets I organize in Northern California. He’s bright, enthusiastic and fun to host. It was a shock when he posted on Facebook about suffering an accident. There were graphic medical photos of extreme frostbite caused by dry ice.

Welp, I’m in the hospital with a life changing situation. It was my own damn fault. Been pushing myself so hard for so long, sleep deprived, pushing myself with arthritis in my wrists. Basically I fell asleep while icing my wrists last night. Woke up 6 hours later, hands were frozen. Went to the hospital, they care flighted me to a burn center in California. It was too late, damage had been done, it’s resulting in a bilateral hand amputation so things are about to get very interesting in my life. I’m doing ok, remaining optimistic. Honestly I’m anxious to get it over with and move on with my life.

To help with costs of hand amputations, one of his co-workers started a crowdfund. I shared it on Twitter, and added a light-hearted comment about helping him to get “new paws” with an article I wrote 6 years ago: Scaly, feathery alternative limbs leap the uncanny valley into the future of prosthetic design (2013). It was about improving the lives of amputees. Instead of hiding prosthetics, they can be featured, like transforming scars with cool tattoos.

I commented about “new paws” before I saw anyone else say it. The crowdfund was his co-workers idea. Those ideas didn’t come from him.

Cooking up a fake attack.

Soon a rumor began spreading on social media. He was accused of causing the amputations on purpose for a fetish. There are cases of people doing self-harm with “body mods” or BIID (Body Integrity Identity Disorder), so the idea has non-zero plausibility. It’s a dysmorphia issue like anorexia. On rare occasions it crosses with furries. Examples range from Stalking Cat in the 1980’s, to the 2018 “Noodles and Beef” story that was on the cover of The Stranger in Seattle. (The writer consulted me for his story based on my tweets about it.)

The situation was concerning. Did I help to spread false money appeals to the public, or contribute to the risk of media glorifying self-harm? Even if it was very unlikely and it was spread from dubious places, the risk was worth taking seriously just in case. I looked in with an open mind about issues I already cover, so this can’t be accused of bias. I checked both sides, but only one was real. Not everything has sides.

Doc Wolverine is a furry MD in general practice/family medicine.

Meanwhile the target spent energy to answer trolls while he couldn’t even easily type. With a stylus in his mouth (or speech-to-text), and nothing to hide, he challenged them to show evidence. They had nothing to show but posts unrelated to him, and fake screenshots with no source.

He explained that he worked with dry ice, and used it after a busy day because he didn’t have regular ice packs ready at the moment. It would have a powerful effect. He’d been overworked, and slept through the harm. (I use melatonin or a weed gummy to pass out sometimes).

He’d never posted anything about intentional amputation — that would be a drastic result of long-term obsession, not a sudden impulse. He did have a history of pain management and motorcycle accidents.

This was a sadistic hoax to torment an innocent guy in a time of need. And the hoaxers didn’t even know that they were piling on someone who was hurt for more than medical reasons. The next part could bring more harassment, but I think it’s important to reveal how they’re even more malicious than they look (and help you decide what responses to give their agenda.)

Pouring salt on the wound.

The victim wasn’t out as gay, and that made a problem about getting home care. He wrote on Facebook:

You know what sucks the most about this situation I’m in? The fact I can’t tell my family. Sure they will find out eventually, but I have to stall that as long as possible. I cant rely on my own parents for support through something like this like I can all the rest of you.

Then a visit from a parent outed his relationship with a partner who was caring for him. Coming out as gay led to losing a parent (at least for the time being.) It’s more evidence that there’s no intentional self-harm here. After the sudden disability, and losing a parent, he told his friends:

Reading the responses and messages just makes me smile and give me that fuel I need to keep pushing on… You all truly are family to me.

I felt bad about unintentionally feeding the hoax with my prosthetics article. There were a few hundred retweets on my posts. I deleted them, and he posted about a break from social media to let the hoax wither away.

For those of you who follow me on Twitter, I’ve been getting a lot of questions regarding this last tweet I made. As many of you are well aware, my situation got a lot of attention and the internet trolls latched onto it and took off with it. I was so relieved to see the majority of furs arent buying into their bullshit. Honestly I’ve got bigger problems to worry about than what some pathetic basement dwelling teenagers want to speculate, but it was really starting to get out of control. Everything I said and did was being used against me, I just got tired of it. I deleted all of my furry content because people were taking my past posts and manipulating them, in addition to straight up photoshopping fake posts. It was getting bad. I figured the best thing for me to do was to take a break from Twitter altogether.

Selfish trolls grabbed attention by kicking an easy target while he was down. But it wasn’t just simple clout-chasing.

A scapegoat for a hate agenda.

The rumors were spread by washed-up pseudo-celebrities tied to hate groups and “Gamergate”, the conspiracy theory/harassment campaign. Their following has nothing to do with furry fandom and only targets it for views. These are grifters who bounce from target to target sourced from chanboards and troll sites, to capitalize on their most gullible followers. (I won’t make that easier by linking their accounts.) These are frontline trolls with 5-figure followings (and not the helpful Frontline that gets rid of fleas.)

(Last screen) Milo’s channel

(Last screen) Milo’s channel

A machine greased with hate to strip-mine the truth.

This hoax is just one example of gaming the algorithms of platforms. Faking a controversy has a goal to move merchandise, subscribers, and donors, at the expense of a newly disabled man in a time of suffering. They’ll say or do anything for clout. You can tell they’re lying if their lips are moving.

The last screen above comes from a familiar face. Milo is the Gamergate grifter who built a following by:

- Mocking gamers as “unemployed saddos.“

- Getting paid by propaganda outlet Breitbart to turn them into a troll mob, and “red-pilling” them as tools for neo-nazis of the alt-right.

- Getting fired by Breitbart for praising pedophilia, going bankrupt and being deplatformed by Twitter for hate attacks.

- Recently trying to mobilize hate groups behind a so-called “straight pride parade.”

When he isn’t spreading transphobia, he’s teasing views at the expense of furries, like the other trolls shown above. It isn’t coincidental, it’s coordinated. Like when an admin of The Daily Stormer (the neo-nazi blog) tried to get “altfurries” out to neo-nazi events coordinated with trolling on their blog. Milo even did get help from a few furries. Dreamkeepers artist David Lillie drew a fursona for him (that he’s been sharing lately) and boosts the “Comicsgate” troll campaign. If you like furry fandom, these trolls inside will use your tolerance to ruin it for you. But you don’t have to let them.

Throwing a wrench in the gears.

This was written with permission to help the victim. But there’s a bigger point to a story of how simple trolling isn’t so simple. They can target me about it to grab their clout, but I personally don’t give a shit about them (or any breed of clout-chaser) because it’s not about me. It’s about what you can do.

Outside of fandom, these trolls are more and more desperate. Their games stopped working thanks to platforms cutting them off from abusing their service.

Deplatformed alt-right personalities Milo, Jacob Wohl, and Based Dragon are all having a collective meltdown together about how their Telegram audiences have stalled at extremely low numbers right now and it's glorious.

Sweet, sweet nazi tears. pic.twitter.com/9GlXcrKqg0

— Gwen Snyder is uncivil (@gwensnyderPHL) September 8, 2019

Milo Yiannopoulos says he is broke. The disgraced right-wing troll is complaining that the major social media companies have effectively cut off his alt-right audience and crushed his ability to make a decent living.#thoughtsandprayers https://t.co/e2JFcbH8cB

— Stone  (@stonecold2050) September 9, 2019

(@stonecold2050) September 9, 2019

Alt-right furries had the same fate after Furaffinity kicked out a few and the fandom showed the door to the rest. Altfurries have no real presence except for being corralled in little hate groups on Telegram where they just wither away now. https://t.co/gP9fqwjXpe https://t.co/MrgPX8Dzxy

— Dogpatch Press (@DogpatchPress) September 9, 2019

Deplatforming WORKS! No person nor platform is obligated to provide a soap-box for these hatemongers. Sure, sunlighting is important, but both sunlighting and deplatforming are valid and complementary strategies to protect communities from alt-right recruitment tactics. https://t.co/aYCu57aQ3W

— Echoen (@echoenbatbat) September 9, 2019

The hoax about “a furry amputated his hands to get new paws” comes from termites eating away at what makes furry fandom special. It’s a place where a newly disabled LGBT man finds support he needs. Spreading this kind of bullshit hurts the weakest people who need help the most. If you see anyone jump on board with it, abate the misinformation. And if they keep doing it, block them, kick them out of your groups, and cut off their funding, because hate doesn’t belong here. Don’t let them in until they stop making scapegoats out of people who truly deserve support. It’s like a little treatment of the Frontline we need.

The hoax about “a furry amputated his hands to get new paws” comes from termites eating away at what makes furry fandom special. It’s a place where a newly disabled LGBT man finds support he needs. Spreading this kind of bullshit hurts the weakest people who need help the most. If you see anyone jump on board with it, abate the misinformation. And if they keep doing it, block them, kick them out of your groups, and cut off their funding, because hate doesn’t belong here. Don’t let them in until they stop making scapegoats out of people who truly deserve support. It’s like a little treatment of the Frontline we need.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, follow on Twitter or send PBS-style support to not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon.

In Flux, ed. Rechan

What constitutes one’s self is never static: one’s mind is always changing a little at a time; the body is continually in flux. Hence the title of Rechan’s short anthology of transformation stories. Transformation fiction bears a particular relevance to the furry fandom as it has provided an introduction to the fandom for many writers and artists. In Flux showcases four different varieties of transformation: sex change (but not gender identity), species shift, non-sapient animal transformation, and finally a combination of the above. Most of these stories also feature depictions of domestic abuse and/or rape, so you have been warned. “Aesop’s Universe: Savages in Space” by Bill Kieffer is set on a generation ship where the passengers live in mono-species recreations of low-tech cultures while the multi-species crew keeps things running behind the scenes. As the lioness passenger Thandiwe is hunting on the savanna deck with her crewman boyfriend Bobby, a hull breach almost kills her, but Bobby gets her to the medical bay in time. During the regeneration process Thandiwe is discovered to have Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, and because the crew apparently values a genetically diverse colonist population over individual rights and because people with AIS are sterile, they clone a fully functional set of male reproductive organs for her and she emerges from the regeneration tank with a massive case of gender dysphoria. I will give Kieffer some props for Thandiwe continuing to use female pronouns in her own internal narrative, unlike most forced sex reassignment recipients in fiction. The way Thandiwe’s family rejects her bears similarities to the way many LGBT+ people find themselves ostracized, even if their reasons differ. The passengers have no context for anything but heterosexuality and cis-genderism thanks to the hormones the crew administers; instead they reject her because they think she’s one of the undead. Honestly, the premise of this story made my skin crawl, but it’s a fair portrayal of an intersex character. Franklin Leo’s “Wild Dog” doesn’t explicitly refer to the animal-people as “were-” anything, but the transformation process is clearly inspired by werewolf myths. When someone gets bitten by an animal-person, they start slowly transforming into the biter’s species, even if they were previously transformed. Riley, who’s built his life and identity around being one of the few African wild dogs to the extent of changing his name when he transformed, finds that identity crumbling after his Dalmatian girlfriend nips him during a blowjob. Part of his identity crisis seems to stem from lingering feelings for his old girlfriend who first turned him into a wild dog, and then left him for a lion. We see a very brief flashback of Riley turning another ex-girlfriend against her will, as if to imply that he deserves what is now happening to him. But it just doesn’t land: the Dalmatian simply comes across as a bitch, and not just in terms of species. I felt this was a weak story with contradicting messages. “Good Boy” by Friday Donnelly initially appears to be a short and simple “revenge TF” story where the human main character is transformed into a non-anthropomorphic German Shepherd after cheating on his boyfriend. But then the character’s mind starts slipping away as he becomes a dog in mind as well as body. Memories vanishing, thoughts turning from anger at the boyfriend and the guy he cheated with to something more along the lines of “I love Master.” It’s short, but communicates the horror well. I didn’t know what to expect going in to Tarl Hoch’s “Never Lick a PCV Vixen”, but it wasn’t a lesbian tanuki getting possessed by a demon that was sealed in an action figure and transformed into a hulking male wolf. The story also explains a little bit on the difference between questionable consent and non-con when Kaiya is discussing why her girlfriend got mad at her with her gay fox friend, and shows it later while the demon is using her transformed body to rail him. Kaiya prefers things gentle, ironically, while her bunny girlfriend likes tentacle rape hentai but doesn’t outright say what she wants in bed: you can practically feel Kaiya’s frustration. This was one of the longer stories, but I also found it one of the more enjoyable if only because it didn’t try to be as serious as the others. SPOILER ALERT: This story is also the only one in the anthology where the transformation is reversed, if temporarily. END SPOILER Something I noticed about the anthology—though I don’t know if it was intentional—was that every transformation in the book was involuntary. Involuntary transformation in particular has been around since the beginning of the genre, but modern TF fiction has brought in an additional element of consideration for the victim in such situations. Your body warping around you, having what little control you had over your form taken away, losing an aspect of, if not your entire, identity. It’s a level of violation far beyond anything possible in real life. After reading In Flux, I find it not that surprising that certain hosting websites (Patreon for one) that have banned portrayals of rape are also banning forced TF fiction.

What constitutes one’s self is never static: one’s mind is always changing a little at a time; the body is continually in flux. Hence the title of Rechan’s short anthology of transformation stories. Transformation fiction bears a particular relevance to the furry fandom as it has provided an introduction to the fandom for many writers and artists. In Flux showcases four different varieties of transformation: sex change (but not gender identity), species shift, non-sapient animal transformation, and finally a combination of the above. Most of these stories also feature depictions of domestic abuse and/or rape, so you have been warned. “Aesop’s Universe: Savages in Space” by Bill Kieffer is set on a generation ship where the passengers live in mono-species recreations of low-tech cultures while the multi-species crew keeps things running behind the scenes. As the lioness passenger Thandiwe is hunting on the savanna deck with her crewman boyfriend Bobby, a hull breach almost kills her, but Bobby gets her to the medical bay in time. During the regeneration process Thandiwe is discovered to have Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome, and because the crew apparently values a genetically diverse colonist population over individual rights and because people with AIS are sterile, they clone a fully functional set of male reproductive organs for her and she emerges from the regeneration tank with a massive case of gender dysphoria. I will give Kieffer some props for Thandiwe continuing to use female pronouns in her own internal narrative, unlike most forced sex reassignment recipients in fiction. The way Thandiwe’s family rejects her bears similarities to the way many LGBT+ people find themselves ostracized, even if their reasons differ. The passengers have no context for anything but heterosexuality and cis-genderism thanks to the hormones the crew administers; instead they reject her because they think she’s one of the undead. Honestly, the premise of this story made my skin crawl, but it’s a fair portrayal of an intersex character. Franklin Leo’s “Wild Dog” doesn’t explicitly refer to the animal-people as “were-” anything, but the transformation process is clearly inspired by werewolf myths. When someone gets bitten by an animal-person, they start slowly transforming into the biter’s species, even if they were previously transformed. Riley, who’s built his life and identity around being one of the few African wild dogs to the extent of changing his name when he transformed, finds that identity crumbling after his Dalmatian girlfriend nips him during a blowjob. Part of his identity crisis seems to stem from lingering feelings for his old girlfriend who first turned him into a wild dog, and then left him for a lion. We see a very brief flashback of Riley turning another ex-girlfriend against her will, as if to imply that he deserves what is now happening to him. But it just doesn’t land: the Dalmatian simply comes across as a bitch, and not just in terms of species. I felt this was a weak story with contradicting messages. “Good Boy” by Friday Donnelly initially appears to be a short and simple “revenge TF” story where the human main character is transformed into a non-anthropomorphic German Shepherd after cheating on his boyfriend. But then the character’s mind starts slipping away as he becomes a dog in mind as well as body. Memories vanishing, thoughts turning from anger at the boyfriend and the guy he cheated with to something more along the lines of “I love Master.” It’s short, but communicates the horror well. I didn’t know what to expect going in to Tarl Hoch’s “Never Lick a PCV Vixen”, but it wasn’t a lesbian tanuki getting possessed by a demon that was sealed in an action figure and transformed into a hulking male wolf. The story also explains a little bit on the difference between questionable consent and non-con when Kaiya is discussing why her girlfriend got mad at her with her gay fox friend, and shows it later while the demon is using her transformed body to rail him. Kaiya prefers things gentle, ironically, while her bunny girlfriend likes tentacle rape hentai but doesn’t outright say what she wants in bed: you can practically feel Kaiya’s frustration. This was one of the longer stories, but I also found it one of the more enjoyable if only because it didn’t try to be as serious as the others. SPOILER ALERT: This story is also the only one in the anthology where the transformation is reversed, if temporarily. END SPOILER Something I noticed about the anthology—though I don’t know if it was intentional—was that every transformation in the book was involuntary. Involuntary transformation in particular has been around since the beginning of the genre, but modern TF fiction has brought in an additional element of consideration for the victim in such situations. Your body warping around you, having what little control you had over your form taken away, losing an aspect of, if not your entire, identity. It’s a level of violation far beyond anything possible in real life. After reading In Flux, I find it not that surprising that certain hosting websites (Patreon for one) that have banned portrayals of rape are also banning forced TF fiction.