Review: 'The Cunning Little Vixen', by Rudolf T?snohlídek

This nature novella about forest life, particularly of a young vixen, in Central Europe around the early 1900s, is barely anthropomorphic. But it is the inspiration for Leoš Janá?ek’s popular 1924 opera of the same title, in which the forest animals are anthropomorphized and sing a lot, so it is worth reviewing here.

This nature novella about forest life, particularly of a young vixen, in Central Europe around the early 1900s, is barely anthropomorphic. But it is the inspiration for Leoš Janá?ek’s popular 1924 opera of the same title, in which the forest animals are anthropomorphized and sing a lot, so it is worth reviewing here.

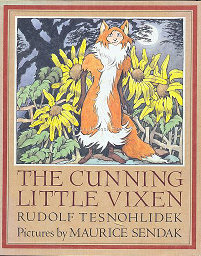

In fact, this book – the only printing that the story has had in English – would not exist if not for the opportunity to publish the 1981 new costume designs for the opera by the popular children’s book author/illustrator Maurice Sendak. It has detailed full-color illustrations every few pages. Actually, The Cunning Little Vixen is the popular English title of Janá?ek’s opera; the title of T?snohlídek’s novella would be Sharp-Ears the Vixen.

NYC, Farrar, Straus & Giroux, April 1985, 185 [+2] pages, 0-374-13346-8, $19.95. Pictures by Maurice Sendak. Translated by Tatiana Firkusny, Maritza Morgan, & Robert T. Jones. Afterword by Robert T. Jones.

This is the pastoral, mildly bawdy (Bartos, the priest, and the schoolmaster are disgracefully drunk much of the time) story, set in rural Moravia (it’s between Bohemia and Slovakia), of how the old game warden Bartos catches a young vixen, names her Sharp-Ears, and brings her home as a pet. The story alternates between Bartos and his elderly friends who play cards and get drunk in Pasek’s village tavern, and Sharp-Ears who escapes back into the forest and, because she has lost her fear of humans, grows up to frequently return to raid Bartos’ cottage of hens and even meat inside the house.

The animals “talk”, but it is clear that this is just T?snohlídek’s way of saying that there is no real difference between the animals and the humans; that we are all God’s children living together in His same world:

Nearby, on the slope facing Black Glen, a blessed fox family lay resting after breakfast. Mother Fox was snoozing because the baby, Sharp-Ears, had kept her up all night. Sharp-Ears was painfully cutting her eyeteeth, and with babies that is always a bother. By noon she had quieted down, but still she clung to her mother’s fur as if it were a skirt and refused to have anything to do with her brothers and sisters.

‘Mommy! Look! What is that?’ whimpered Sharp-Ears. All the little ones – Black-Nose, Little-Tail, Feather-Catch – instantly stopped playing and crowded around the strange creature [a frog] who seemed to have fallen out of the blue sky into their midst and was now sitting there breathless, eyes popping out as if it had just sprinted a mile. Sharp-Ears sniffed it.

‘Oooo, it’s cold!’ she cried.

‘And naked as a rock!’ exclaimed Feather-Catch, surprised.

‘It left its tail at home,’ added Little-Tail in wonder..

‘Mommy, please,’ said Sharp-Ears in her most pleading tones, ‘is it good to eat?’ (p. 19)

[Bartos brings home Sharp-Ears.] Another detail confirmed Sharp-Ears’s identification of the she-human: the female began to bark at the forester so furiously that he could not manage to answer. At home, Mama Fox had carried on just like that when her papa had come back late at night, singing and shouting, with his fur rumpled and torn, talking nonsense and refusing to say where he’d been. The old human behaved just like Papa Fox, who would pacify his wife by bringing her some rare catch, a hen or a duck, a partridge or a young hare. The forester planted his feet wide apart and proudly displayed Sharp-Ears to the she-human while the little fox shivered all over with fear. The woman stared at him suspiciously for another moment, then stopped her torrent of talk and declared, ‘You’re just bringing fleas into the house.’ (pgs. 24-25)

[Bartos is muttering drunkenly to his dachshund, Catcher.] ‘The Good Lord created the world in perfection, but He went wrong in one thing, Catcher, and that one thing lost us paradise. It was woman, dog damn it. Just count, Catcher. He created the whole world in six days. On the seventh – Saturday, according to the Jews – the world rested. And then, on Sunday, there was man walking around the Garden of Eden talking to animals just like I’m talking to you right now. But you know something? Sunday is a lousy day, disgusting, endless as the ocean. I can just imagine how that man felt – no taverns, no friends, no card games, no nothing!’ (p. 68)

[Sharp-Ears meets a tod fox.] Unable to conceal his admiration, he asked courteously, ‘Do you enjoy sports, miss?’

‘Oh,’ she said with a charming smile, ‘and how! You’d be surprised how I can climb, but that’s not proper in the presence of gentlemen. I used to climb into the pantry of the forester’s house. I felt perfectly at home there.’

‘The forester’s house!’ He marveled and bowed respectfully.

‘I grew up there. My upbringing is a bit human.’

Astonished, he lowered his tail all the way to the ground. ‘Forgive me if I’m perhaps detaining you.’

‘Not at all,’ answered Sharp-Ears.

He bowed again, placed his left front paw on his chest, and, totally enchanted, introduced himself. ‘Golden-Stripe, the yellow-furred fox from the Deep Ravine.’ (p. 138)

It’s Bartos’ job to protect the villagers’ livestock by killing the marauding vermin, but he has a soft spot for Sharp-Ears, who is only doing what God intended foxes to do. As Sharp-Ears matures, takes a mate, and has cubs, Bartos philosophizes about nature and the cycle of Life in the forest. An individual like Sharp-Ears, even if she escapes getting killed, will eventually grow old and die; but the forest lives forever. (In T?snohlídek’s story, Sharp-Ears escapes to raise her cubs in the forest. In Janá?ek’s opera, she is shot and killed. But you know what Bugs Bunny said in What’s Opera, Doc?: “Well, what did you expect from an opera; a happy ending?”)

Jones’ lengthy Afterword explains fascinatingly how this novella was actually spread over almost forty years and was due to “a committee”. First there was an almost-anonymous old Austro-Hungarian game warden or forester named Korinek, who in the 1880s told amusing stories to a young landscape artist, Stanislav Lolek, about a village forester and other locals including a schoolteacher and a priest, and the nearby wildlife, especially a fox who raided their henhouses and escaped all their traps. Jump forward to 1920. Dr. Bohumil Markalous, the owner of Lidove Noviny (The People’s News), the main newspaper in Brno, Moravia’s regional capital, was looking for something new to publish. He found about two hundred old sketches of those long-ago stories gathering dust in Lolek’s studio. At that time newspapers were just beginning to publish comic strips, but a children’s section of heavily-illustrated serialized stories (that is how The Adventures of Pinocchio began, in an 1880s Italian newspaper) was common. Usually the stories came first and the drawings were made to illustrate them, but Markalous got the idea of writing an original children’s story around the already-existing cartoons. He bought them from Lolek and told his staffroom editor, Arnost Heinrich, to have the story written. Nobody wanted the job. So Heinrich literally dumped the dusty drawings on the desk of Rudolf T?snohlídek, the least popular writer there (with the other staffers), and assigned him to write a light children’s story around them.

It is impossible to imagine a writer less suited than Rudolf T?snohlídek to write a light children’s story.

His life, as interpreted by his journalistic colleague Bed?ich Golombek, was a melodramatic tragedy imbued with pessimism, darkness, melancholy and decadence, a life plagued from childhood by feelings of sadness and social exclusion. (Wikipedia)

T?snohlídek was born in 1882. His father was a knacker who killed and skinned animals for their pelts and for meat for local butchers. According to T?snohlídek, he was terrified throughout his childhood by the smell of blood and the shrieks of the animals being killed. “Young Rudolf often ran from the screams of dying beasts and hid in the garden outside his house.” (p. 168) At 19, he was traumatized when he watched helplessly as a friend drowned in front of him, crying to T?snohlídek to rescue him. He fell in love with a tubercular girl who would be called a goth today; she dressed in black, drank absinthe, and worshipped death since she was sure she was dying anyway. They married, and she killed herself on their honeymoon in Norway, taunting T?snohlídek for not having enough nerve to join her in a suicide pact. He was not believed at first, and was the defendant in two murder trials before being acquitted. He joined Lidove Noviny – its motto was “The Newspaper for Happy Reading” -- as a writer, where the rest of the staff soon complained that he was an aloof loner whose idea of fun was to write pessimistically morbid and depressing poems. He married a second wife, who soon ran off with a less-gloomy doctor. A Wikipedia photograph shows a man who looks to be in his sixties going on his seventies, but T?snohlídek was only 47 when he committed suicide in 1928.

T?snohlídek’s Liška Bystrouška (Vixen Sharp-Ears; Janá?ek named his opera P?íhody Lišky Bystroušky; The Adventures of Vixen Sharp-Ears) appeared in Lidove Noviny with Lolek’s old cartoons from April 7 to June 23, 1920. To everyone’s surprise, it was a smash hit. T?snohlídek did not know how to write for children, so he wrote a story for all ages (with cheerfully drunken humans); a poetic paean to nature and the Central European forests. Adults liked it better than the children did. This was very fortunate because it otherwise might not have come to the attention of Leoš Janá?ek, a regular reader of the newspaper. T?snohlídek described himself as in awe when the famous playwright, already considered a national treasure throughout Czechoslovakia, visited him to ask his permission to turn it into an opera. The newspaper serial became well-known throughout Moravia – T?snohlídek published it as a book in 1921 with Lolek’s illustrations – but because he had written it in the local Moravian dialect, modern Czech editions have had to “contain sizeable glossaries of odd spellings and archaic words, many of them not heard even in Brno for a good half century.” (p. 185) Janá?ek’s opera premièred in Brno in November 1924 and quickly became internationally popular, while T?snohlídek’s story was not translated into other languages and remained unknown outside Czechoslovakia. Until this book.

(After Liška Bystrouška, T?snohlídek started a series of articles about Moravia’s many caves and caverns – in the last days of World War II, the Nazis hid some of their looted art treasures from throughout Europe in them. T?snohlídek’s original articles always emphasized the grandeur of the stalactites and stalagmites, and the peacefulness of living in the dark underground. Lidove Noviny always heavily rewrote the articles into a straightforward description of the caves, when it did not throw them out altogether, and ordered him to remember the paper’s motto and write more cheerful poetry. In January 1928, to show the newspaper what he thought of it, T?snohlídek shot himself in the staffroom. When his third wife got the news, she also committed suicide. Wow!)

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

Gah! I think you picked one of the least attractive looking stagings of that opera as an example.

Check out the Berlin Opera version ... the backgrounds and the animal costumes are outstanding, and avoid the awkward "opera singer in pajamas" look that seems to plague many other versions of the opera:

Hey, some of us have a thing for opera singers in pjyamas . . .

The costume design is a lot prettier - albeit requiring the mask to be removed for singing - but the video's just a teaser, not the complete scene. (It's also in some strange language that I don't understand, but so is the English version. ;-)

Thanks for finding it, though! I wonder how many stagings there have been in total.

How many operas with anthropomorphic animals are there? There is Janá?ek’s 1924 The Cunning Little Vixen, Joanna Lee’s 2010 Krazy Kat, based on George Herriman’s newspaper comic strip (and Lee’s 2010 cantata The Chronicles of Archy, based on Don Marquis’ newspaper poems about the world-traveling cockroach), and Tobias Picker’s unlistenable 1998 The Fantastic Mr. Fox, based on Roald Dahl’s children’s novel. http://anthrozine.com/site/lbry/yarf.reviews.u.html Are there any others?

Fred Patten

I was thinking more stagings of this particular opera, but that's interesting too. :-)

This was a excellent review article. I'm very fond of *The Cunning Little Vixen*, and I saw a terrific production at the Houston Grand Opera several years ago. I didn't know anything about the origin of the story, though.

In the opera, there is a very strange father-daughter dynamic between the Forester and Sharp-Ears. Sharp-Ears also seems to have something of a crush on the Forester, and periodically goes into hysterics when she thinks that humans aren't taking her seriously because she is "just a vixen." (She is actually shot by the hunter while lecturing him on his disregard for vixen/human equality.) I'm curious to read the original to compare it to the opera.

Post new comment