Review: 'Carbonel, The King of the Cats', 'The Kingdom of Carbonel', and 'Carbonel and Calidor', by Barbara Sleigh

I usually select the books that I review on my own initiative, but this review of the Carbonel novels was suggested/inspired by Rakuen Growlithe. He asked, in a comment to my review of Windrusher and the Trail of Fire:

There were two cat books I read as a kid and found really good but I don't recall ever seeing someone in the fandom mention them, which I find a bit sad. Did you ever read either Carbonel or The Kingdom of Carbonel? They were about Carbonel, the king of the cats, his service to a witch, relationship with two children and, in the sequel, his kittens and authority?

I had read them over fifty years ago and remembered enjoying them. On investigating, I found that there was a third Carbonel novel that I had not known about; and that, after being out of print for decades, all three have been reprinted recently and are again available. Fortunately, the Los Angeles Public Library and the County of Los Angeles Public Library between them have all three, so I did not have to buy copies.

I have enjoyed rereading the first two, and reading the third for the first time, very much. Thank you, Rakuen, for reminding me of them. (By the way, do you remember whether you read the British edition, the American edition, or was there a separate South African edition?)

The Carbonel books, “Age Level: 9 and up | Grade Level: 4 and up”, by Barbara Sleigh (1906-1982), are in the tradition of magical adventures for modern children that were popular around the 1950s. I remember that Five Children and It and most of the late Victorian and early Edwardian children’s fantasies by E. Nesbit came back into print; Edward Eager began his novels that started with Half Magic; Mary Norton had her series of Borrowers books; and C. S. Lewis wrote the Chronicles of Narnia. There were several single children’s fantasies that I enjoyed at the time, but the only two whose titles I remember are Mistress Masham’s Repose by T. H. White, and King Lizard by William Herschell.

Carbonel, The King of the Cats

There were the two (at the time) Carbonel novels by Barbara Sleigh. I read the American editions, but there was no mistaking that these were British books first.

There were the two (at the time) Carbonel novels by Barbara Sleigh. I read the American editions, but there was no mistaking that these were British books first.

In Carbonel, The King of the Cats, ten-year-old Rosemary Brown has just gotten out of school for six weeks when her class has broken up at the end of the spring term. She lives with her mother in a shabby flat in Tottenham Grove.

Rosemary and her mother lived at Number Ten, in three furnished rooms on the top floor, with use of bath on Tuesdays and Fridays, and a share of the kitchen. It was not a very pleasant arrangement, because the furniture was ugly (most of it was covered with horsehair that prickled, even through a winter dress), and the bathroom was always festooned with other people’s washing. But it was cheap and would have to do until they could find some unfurnished rooms. Then they would be able to use their own comfortable, shabby belongings again. (American ed., pgs. 12-13)

Mrs. Brown does sewing to earn money, and she has just gotten three weeks work mending sheets and curtains for rich Mrs. Pendlebury Parker, so she will not be home for the first half of Rosemary’s vacation. (“‘And perhaps,’ said Rosemary, brightening, ‘you’ll be rich enough afterwards to buy one of those things to make your sewing machine run by electricity.” (p. 15) So the reader sees that they are quite poor.)

Rosemary decides to get her own job while her mother is away from home. She could sweep and polish and wash. But she doesn’t have a broom, so she walks to Fairfax Market to buy one. After arriving just as the Market is closing, it looks like Rosemary is out of luck until a black cat lures her to a disreputable-looking old woman who turns out to be Mrs. Cantrip, a witch who has decided to retire. The witch sells Rosemary her broom (an old-fashioned twig besom), and the cat for three farthings extra. Both are magic, of course, and Rosemary learns that she can talk to animals while holding on to the broom (which can also fly).

Rosemary decides to get her own job while her mother is away from home. She could sweep and polish and wash. But she doesn’t have a broom, so she walks to Fairfax Market to buy one. After arriving just as the Market is closing, it looks like Rosemary is out of luck until a black cat lures her to a disreputable-looking old woman who turns out to be Mrs. Cantrip, a witch who has decided to retire. The witch sells Rosemary her broom (an old-fashioned twig besom), and the cat for three farthings extra. Both are magic, of course, and Rosemary learns that she can talk to animals while holding on to the broom (which can also fly).

The cat, Carbonel, explains that he is a Prince of the Royal Blood (nothing but the best for Mrs. Cantrip), and that Rosemary has broken half the spell that made him Mrs. Cantrip’s familiar by buying him with three old farthings with Queen Victoria’s portrait on them. But Carbonel is still bound to be Rosemary’s servant, unless they can find Mrs. Cantrip’s old cauldron and steeple hat which were part of the spell that enslaved him, which must be done before the last of the twigs drops off the besom. Rosemary, of course, would not keep Carbonel against his will, and the two set out to release him from the spell.

The rest of Carbonel, The King of the Cats is about the search for the witch’s objects, with asides such as how Carbonel gets the Browns’ cat-hating landlady to accept him. Rosemary and Carbonel are invited to accompany Mrs. Brown to Mrs. Pendlebury Parker’s estate to become playmates of her nephew John, and he quickly joins them in the magic search. The two children and the black cat wander through the city that is never named but is certainly London, finding the magic items one by one, but needing to earn them from their new owners since it would not do to steal them. Another impetus to help Carbonel win his freedom is that the Kingdom of the Cats is falling into chaos through misrule by the Alley Cats without the rightful heir to take command.

The conclusion, in which the magic broom that allows the children to understand Carbonel’s speech is burnt, seems to mean the end of all magic adventures. Carbonel, The King of the Cats is still enjoyable reading for adult fantasy fans as well as for children, but the story does show its age. For one thing, it was obviously written before British currency was decimalized. Prices are in shillings and pence, and who knows what a farthing is any more? For a second, are preadolescent children allowed to “go out and play” all day any more? Modern guides to “child care” and “planned play activities” imply that children today can hardly do anything outside the home or school without a parent or guardian in attendance. For a third, the novel gets away without mentioning any father. In the mid-1950s, British families without fathers were unfortunately common; it went without saying that the fathers had been killed during World War II, either in the military or in the Blitz.

The Kingdom of Carbonel

I remember the two Carbonel books as appearing almost simultaneously, but in fact they were published five years apart, although in story time The Kingdom of Carbonel is set only a year later. The Brown’s position has improved tremendously due to Mrs. Brown’s dressmaking being recognized as high quality, and they have moved from London to the small town of Fallowhithe. It is the holidays again, and Rosemary is waiting for John to come and play, when Carbonel arrives unexpectedly. He obviously wants the children to do something, but without the witch’s besom they cannot understand him. After a couple of frustrating attempts at pantomime, the children decide to see Mrs. Cantrip again and find out if there is any other way that they can talk with cats. Mrs. Cantrip insists that she has retired from witchcraft, but she gives them the prescription for Prism Powder to be made up by the druggists Hedgem and Fudge.

I remember the two Carbonel books as appearing almost simultaneously, but in fact they were published five years apart, although in story time The Kingdom of Carbonel is set only a year later. The Brown’s position has improved tremendously due to Mrs. Brown’s dressmaking being recognized as high quality, and they have moved from London to the small town of Fallowhithe. It is the holidays again, and Rosemary is waiting for John to come and play, when Carbonel arrives unexpectedly. He obviously wants the children to do something, but without the witch’s besom they cannot understand him. After a couple of frustrating attempts at pantomime, the children decide to see Mrs. Cantrip again and find out if there is any other way that they can talk with cats. Mrs. Cantrip insists that she has retired from witchcraft, but she gives them the prescription for Prism Powder to be made up by the druggists Hedgem and Fudge.

It was a large, old-fashioned building. Looking above the cars that honked and hurried, they could see the name in gold letters, as well as two great glass bottles full of glowing red and green liquid that have been the sign of a dispenser of medicine in England since the days when few people could read. (pgs. 36-37)

The prescription is for some of the red liquid, which they know works because the druggist’s assistant accidentally spills some on his hand and licks it, and is able to understand Carbonel. The prescription says, “Half a teaspoon to be taken after meals as required.” The children take it, and are able to understand not only Carbonel but also the caterpillars and beetles in the garden.

What Carbonel wants is for the children to watch over his two royal kittens while he is away.

‘But why must you go?’ persisted John.

‘Once every seven years I and my royal brothers are summoned to the presence of the Great Cat.’

‘But who are your royal brothers?’ asked Rosemary.

‘You must not think that I am the only cat king,’ explained Carbonel. ‘Every city in the world where there are cats has a king to rule over them, just as I rule over the cats of Fallowhithe. When the Summons comes, we must all obey. There will be lean, blue-eyed cats from Siam, long-haired cats from Persia, great tawny jungle cats, and thin, big-boned cats from Egypt. Cats of every color – black as coal, white as milk, gray as woodsmoke. Whatever the color, whatever the kind, when the Summons comes we all must answer.’ (p. 49)

Carbonel and his queen, Blandamour, entrust their young kittens, black Prince Calidor and tortoise-shell Princess Pergamond, to the children. But as soon as the adult cats leave, the high-spirited kittens are getting into mischief, encouraged by their old nurse, the tabby cat Woppit.

The next day the children are enjoying an outing in the countryside (they can understand all of the birds, animals, and insects around) where a new housing development is joining their community of Fallowhithe to that of Broomhurst, when they come upon Mrs. Cantrip and an apprentice witch, Miss Dibdin, acting very mysteriously and up to no good. Tudge, an old farmcat, explains that they are working for “Her Royal Grayness”, Queen Grisana of the Broomhurst cats. When the king cats get the Summons, their queens are supposed to rule their kingdoms while they are gone. But Grisana is ambitious, and as soon as the new construction connects Broomhurst to Fallowhithe, she plans to annex the Fallowhithe kingdom whose Queen Blandamour is expected to be too gentle to resist.

The rest of The Kingdom of Carbonel tells how Rosemary and John, with the planning of Blandamour and her wise counselor Merbeck, and a magic rocking chair that Rosemary has liberated from the witches, spy on the two witches and the cats of Broomhurst to learn their plans, but are unable to stop Mrs. Cantrip and Miss Dibdin from kidnapping the royal kittens.

‘Your Majesty,’ said Merbeck, stepping forward. ‘I am old, my claws are blunt and my flanks are lean, but my blood races like a young animal at the tale of such wickedness! If your subjects know of this foul plot too soon, there will be bloodshed. And that we must avoid. Hot-headed young animals would bandy words with Broomhurst cats, and that would lead to blows. There would be border incidents, and that lies into enemy country and eventually open war. I have seen it happen before.’ (p. 136)

So they must find the kittens in secrecy. Thanks to Miss Dibdin’s amateurish magic, John turns invisible; which causes new problems but makes it easier to find the kittens than they expect. However, there is still the war between the two cat kingdoms to head off, and Mrs. Cantrip has a final nasty bit of magic to use. All turns out well, but Rosemary and John have to give up their ability to understand the speech of animals. Once again all the plot threads seem to be neatly resolved, leading to the belief that this was the final novel.

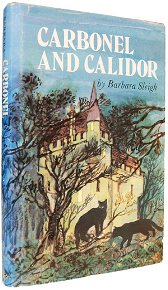

Carbonel and Calidor

For many readers, it seems to have been. Carbonel and Calidor; Being the Further Adventures of a Royal Cat, was not published until eighteen years later in England, and there was not an American edition as there had been of the first two novels. Few readers of the first two books in their heyday ever knew that there was a final volume. Fortunately, the New York Review Children’s Collection has reprinted all three in the last decade.

Carbonel and Calidor is more of a sequel to The Kingdom of Carbonel alone than to both earlier books. Like The Kingdom of Carbonel, it is set one year later. Due to the events at the conclusion of The Kingdom of Carbonel, none of the characters have any memory of the magic. New construction in the Fairfax Market is forcing Mrs. Cantrip and Miss Dibdin, now old friends of the Browns, to move. When Rosemary and John visit them, the new nice Mrs. Cantrip is still very friendly, but Miss Dibdin is acting guiltily, and she has gotten a pet black cat named Crumpet. The children are allowed to choose a present from a box of Miss Dibdin’s party crackers, and Rosemary picks an odd one that has a witch’s hat and a “Golden Gee-Gaw” (a magic ring) inside it. Wearing the magic ring allows them to understand Carbonel when he reappears. Carbonel is frustrated because his son Calidor, now a rebellious adolescent, has rejected his planned marriage and run away from the Falllowhithe cat kingdom. The children learn that he has become the familiar of Miss Dibdin, who is experimenting with magic once again. She has temporarily gone with Calidor to nearby Highdown, where coincidently John’s Uncle Zachary lives, to look for a home for Mrs. Cantrip and herself.

The children go to Highdown to help Uncle Zack in his antiques shop for a sale. They find that Miss Dibdin has become a roomer of Mrs. Witherspoon of Tucket Towers, the local witch of Highdown, to copy her magic. Calidor has become Miss Dibdin’s familiar to hide, to get out of the arranged marriage to “sly-paws” Melissa, the royal daughter of King Castrum and Queen Grisana of Broomhurst’s cat kingdom (Calidor loves Dumpsie, a common tabby); and to study magic with Mrs. Witherspoon’s familiar, Mattins.

The children are distracted by accidental misuse of the magic ring bringing a road’s worth of cats’-eye reflectors to life as crab-like Scrabbles. Then they meet Dumpsie (whose real name is Wellingtonia), and learn that Mattins has betrayed Calidor to Queen Grisana and Princess Melissa, who plan to punish him severely with all the other Fallowhithe cats for the insult of Calidor’s rejecting the marriage. And Carbonel has disappeared! While passing out flyers for Uncle Zack’s antiques sale, they overhear Mrs. Witherspoon and Miss Dibdin arguing. Mrs. Witherspoon has seized Carbonel and, on the advice of her toad Gullion, locked him up until he agrees to become her new familiar. He is guarded by the Scrabbles. The two witches part company as rivals. When Calidor is informed, he agrees to return to Fallowhithe immediately to lead its cat kingdom until Carbonel is rescued.

Rosemary and John have more magical misadventures before the witches and the Broomhurst cats are defeated. Once again all the loose ends are wrapped up. The book ends with Calidor’s betrothal to Dumpsie (who will become Queen Wellingtonia), and a hint that Carbonel and Blandamour are ready to retire and become regular housecats at Rosemary’s home.

Rosemary and John have more magical misadventures before the witches and the Broomhurst cats are defeated. Once again all the loose ends are wrapped up. The book ends with Calidor’s betrothal to Dumpsie (who will become Queen Wellingtonia), and a hint that Carbonel and Blandamour are ready to retire and become regular housecats at Rosemary’s home.

The blurbs say that the three novels can be read in any order, but it is best to read them in the order that they were written. Sleigh showed an admirable talent for making the three stories different enough from each other that they do not seem like just the same story repeated with minor variations. The major complaint, which is excusable in stories for nine-year-olds, is that Rosemary and John keep learning what to do next by too easily eavesdropping on the villains. Wikipedia notes,

The first two books are more closely associated than the third. It has been noted that Carbonel has few real cat characteristics. He is more like Edith Nesbit’s Psammead in Five Children and It [1902], speaking ‘with the voice of tart and faintly impatient adulthood.’

The three books are too good to be forgotten, so kudos to the New York Review for reprinting them in its Children’s Collection.

“Carbonel”, by Barbara Sleigh. Illustrated by V. H. Drummond.

London, Max Parrish, 1955, hardcover 9/6 (188 pages).

As “Carbonel, The King of the Cats”, by Barbara Sleigh. Illustrated by V. H. Drummond.

(1) Indianapolis, The Bobbs-Merrill Co. Inc., August 1955, hardcover $3.25 (253 pages);

(2) NYC, New York Review Children’s Collection, October 2004, hardcover $16.95 (216 pages).

“The Kingdom of Carbonel”, by Barbara Sleigh. Illustrated by D. M. Leonard.

(1) London, Max Parrish, 1959, hardcover 10/6 (254 pages);

(2) Indianapolis, The Bobbs-Merrill Co., Inc., 1960, hardcover $3.50 (287 pages);

(3) Illustrated by Richard Kennedy, NYC, New York Review Children’ Collection, June 2009, hardcover $17.95 (240 pages), Kindle $9.87.

“Carbonel and Calidor: Being the Further Adventures of a Royal Cat”, by Barbara Sleigh. Illustrated by Charles Front.

(1) Harmondsworth (London), Kestrel Books, March 1978, hardcover £3.25 (214 pages);

(2) NYC, New York Review Children’s Collection, October 2009, hardcover $17.95 (224 pages), Kindle $9.87.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

I LOVED these and they're among the childhood books I've hung on to. I was reading secondhand Puffin paperbacks in the 1980s; I got hold of all three around the same time, luckily in the correct order.

I didn't notice when I first read them, but it's obvious now from the illustrations that there's a biggish time gap between the first and third books. John goes from wearing schoolboy shorts and a blazer in Carbonel to flared jeans in Carbonel and Calidor!

~ Huskyteer

I suppose that we owe the Harry Potter books a debt of gratitude for making children's fantasy so popular once again that there has been a new market for modern reprints of the books of the 1950s. I wondered when the Harry Potter novels started appearing around the end of the 1990s why the public was going crazy for them when there were already so many magical children's fantasies. I had forgotten that most of the earlier books had been out of print for a generation or more, and that there had not been anything like them for ten years or more when the Harry Potter books started appearing.

Fred Patten

As an aspiring children's author, I'm delighted that titles for kids are getting more prominence and more marketing budget, but less delighted with the number of times people have said "So you're going to be the next J. K. Rowling, are you, ha ha?"

~ Huskyteer

If people asked me whether I was going to be the next Mark Zuckerberg, I'd laugh . . . sure, you can hit the jackpot if you're dedicated and lucky, but a sustainable income is far more achievable. For writing, like visual art, it's a tough road - a lot of people give up before they get there - but it exists.

I'd rather it weren't looked at as being a children's book. Obviously some stories appeal more to children or are written simply but I think there are others, like Harry Potter, which are suitable for adults and children. Anyone can pick up Harry Potter, read it easily and enjoy it. I think even if it's aimed at children a well-written book can be read by anyone. I'd think Redwall also falls into that category. Similarly my parents never stopped me reading an "adult" book (in this case adult not meaning erotic) because they figured if I was able to read it then that was good enough. There wasn't that much of a distinction between adult and children's books, there were just books and I could read any one I wanted.

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

~John Stuart Mill~

Would that my parent was like that! I tend to keep what I'm reading hidden from my mother; she once confiscated a book I'd been reading on self-harm (Cut, I think it was called) and then had me talking to a therapist!

My parents allowed me to read anything that was around our house. I was reading my mother's Perry Mason mysteries before I was reading Dick and Jane primers in elementary school, which got my teacher complaining to my mother that I was always finishing my books immediately instead of reading just the next two or three pages that were assigned. I read a Classics Comics adaptation of Dumas' 'The Count of Monte Cristo', and I liked it so much that I wanted to read the real book. All the copies the public library had were abridged, which disappointed me. I finally found a complete copy in, of all places, our own garage, in a box of my dead grandfather's stuff. It was a 19th-century edition that my mother would not let me read! She said that I would ruin my eyes, because it was about 1,000 pages in 6 point or 8 point type; very tiny. She threw it away, but I dug it out of the trash and read it anyway. I think the real reason she would not let me read it was that it was unexpurgated; very adult. The comic book and the public library editions told about all the friends the Count had who helped him on his secret missions; but the uncut version said why he had so many friends; he got them hooked on free hashish! I liked my father's Nero Wolfe mysteries much better than any of the library's children's books. Then one day when I was 9, my father brought home a "new book" s-f novel from the library, 'Sixth Column' by Robert A. Heinlein. My father decided that he did not like s-f, but I read it before he returned it to the library, and I was hooked! I have been an obsessed fan of s-f and fantasy ever since.

Fred Patten

My parents let me read most things, but they did hide away a few titles when I started roaming the house in search of more book prey. One was Erica Jong's Fear of Flying.

~ Huskyteer

Fear of Flying is on my list of books I need to read. (It's one of the few on the list that wasn't written by Stephen King.)

Somehow it seems the appropriate response to that might be to raise your eyebrows and say, in your most mysterious voice, "Maybe I already am," then walk away without further explanation.

— Chipotle

Thank you for reviewing these. Hopefully it will get more people to read and enjoy them. I think I read The Kingdom of Carbonel first and then Carbonel (My copy, a puffin version with the same picture as in here but slightly rearranged text, doesn't mention a subtitle.). When I read them I memorised the rhyme that was meant to summon Carbonel and I can still recall it. ^^ It's really quite a nice little rhyme.

I read the British versions of the books. I don't think there are many non-South African books that get a specifically South African printing. I think the majority of books here come from the UK but we do also get them from the US. Sometimes we even get both versions which can be confusing as the titles sometimes change. I almost bought the same book twice because of that. If I look at the back of The Kingdom of Carbonel it says "For copyright reasons this edition is not for sale in the U.S.A." and gives the price for a number of countries.

United Kingdom 25p

Australia $0.75

New Zealand $0.75

South Africa R0.60

Canada $1.15

Try finding a book that price now!

I'm not sure if it's that they are old, British or just use archaic terms for the witches but I think reading these sort of books is very good just in terms of learning. It's when I learned the word "widdershins" which I've almost never seen since (and spell check doesn't recognise) and is a great way to learn about other times and cultures. It's that reason why I despair so much when I see them removing "nigger" from Twain's works and "translating" The Iliad into "South African." There's more to these works than just the words and stories. They are a glimpse of a different time and place when you remove that you lose the heart of the work and that's just as important as the story itself.

"If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind."

~John Stuart Mill~

> When I read them I memorised the rhyme that was meant to summon Carbonel and I can still recall it.

Snap :) My copy of Carbonel is probably priced at 25p too; I don't think it's quite old enough to be in shillings and pence.

~ Huskyteer

The Los Angeles Public Library still has the first 1955 American edition of “Carbonel, the King of the Cats”, so I have not seen the new 2004 NYRCC edition. Somebody, read it and tell me that it hasn’t been updated by changing the shillings-and-pence prices into modern decimalized prices! I did notice that the U.S. edition Americanizes the spelling of grey to gray.

Many Americans were furious when the American publisher of the Harry Potter books Americanized the text. The most notorious example is changing the title of the first novel from “Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone” to “Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone”. Not changing the text of many British fantasies is how I learned many archaic and non-American words. Widdershins was one of them. “Carbonel, the King of the Cats” teaches that the proper name for the very obsolete high-crowned women’s hat called ‘witch’s hat’ today is a steeple hat. I recently commented elsewhere that the Horatio Alger novels are a treasure-trove of forgotten 19th-century American slang.

In the late 1960’s there was a s-f/fantasy mail-order bookseller in San Francisco, J. Ben Stark, who imported many British s-f and fantasy novels that did not have American editions for sale to American fans. He got into legal trouble and I think was shut down by court order for selling those “For copyright reasons this edition is not for sale in the U.S.A.” editions. Today, fortunately, Americans can use the Internet to mail-order British books directly from Amazon.co.uk.

(Come to think of it, the books that I got from Ben Stark included the very British children's fantasies by Will Nickless that used talking animals who were members of a posh upper-class Edwardian club to satirize British social and political practices. Are they in print today? They were very adult in tone and would be enjoyed by Furry fans today. "Owlglass", 1964; "The Nitehood", 1966; "Molepie", 1967; and "Dotted Lines", 1968. For example, in "The Nitehood", Mr. Odysseus Harris, a social-climbing middle-class rat, becomes wealthy and engages Beddoes Waterbrook (hare), an Oscar Wilde-ish poet, as his valet. Harris wants a knighthood, which are supposedly only for deserving commoners and not for sale, but Waterbrook understands human politics and knows how these things are arranged.)

Generally I object to the word "nigger" today, but I read somewhere that Mark Twain stated that he wrote "The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn" partly to document what social customs in America along the Mississippi River were really like before the Civil War. In that case, I agree that "nigger" should be left in, although I also agree that the unexpurgated text should be left to college classes, and maybe high school with parental consent.

Fred Patten

Parental consent to read the word "nigger"? In high school? Come on. Students reading Twain (except in the case of required reading) are probably mature enough to handle it.

I think the first time I came across the word in literature was when I was twelve, and even then it didn't really phase me. (Another book I read around the same time had it as "n----", and that upset me because I was reading censored material--who knows what else had been changed?)

Just doing a little research for my own little article (written by someone else but I have to top and tail it) about Carbonel and I came across this gem. Thank you for reviewing one of my childhood favourites. I don't know which is better, the review or the comments which mirror my own views on massaging texts to fit today's language.

The most outrageous example that I know of is an adult s-f novel, not a children's book: Lest Darkness Fall by L. Sprague de Camp. It was written in 1940. The first chapter is set in modern Rome before the protagonist time-travels to 6th-century Italy. When it was reprinted in the 1970s or 1980s, somebody decided that it should be "modernized" to the present, so the first chapter was revised from 1940 Rome to 1970s or 1980s Rome -- except that they did a very poor job of it. So there were descriptions of 1970s or 1980s building and styles, and the references to Fascist Blackshirts were removed, but they left in the references to Benito Mussolini as the current prime minister, and Franklin Roosevelt as the current U.S. president.

Fred Patten

I'm disgusted by this, I don't know what they could have been thinking. I've been watching The Hardy Boys, Trixie Belden and Enid Blyton, what they've done to those is a tragedy.

Post new comment