Feed aggregator

The 5 Best Furry Discord Servers

Xege Kheiru, Writer, Furry

08 March 2022

Xege Kheiru, Writer, Furry

08 March 2022

What’s Discord?

If you’ve been living under a rock for the past 5 years, then you might have no clue what this article is even about. Not to worry, we’ll catch you up to speed on everything you need to know about furry discord servers before we jump into the 5 best servers.

In short, Discord is a communication service that allows its users to message, voice and video call, stream their screens etc. You can use it to chat with friends, meet new people and most importantly build communities. One of the main features of Discord however are servers; they’re like group chats but for potentially thousands of people, with hundreds of text channels for hundreds of different subjects. Thousands of great communities have been built just through discord, and furry communities are no exception.

Discord’s emphasis on individuality and innovation, allowing its users to have unique banners, animated profile pictures, assign roles to a server’s members, unique permissions for specific roles, assistant bots, listening parties and more gives users almost complete freedom to do whatever they want. This makes it ideal for building and maintaining large communities.

Discord Logo

Image by PCMag via PCMag

Discord Logo

Image by PCMag via PCMag

Then, What’s a Furry Discord Server?

As you might’ve been able to guess, a furry discord server is just a discord server exclusively for furries. While there is no way of verifying whether or not someone is actually a furry or just a troll, this issue is rectified pretty quickly by discord’s handy permanent ban feature. As well as this, most furry discord servers go through a validation process that makes users discuss their likes and dislikes, fursona (if you have one), age etc.

Furry communities can even have sub-communities. For example, furry Minecraft communities, furry role-playing communities or rather 18+ furry communities, where users can share NSFW (furry porn) art. While we are going to go through a list of the 10 (what we think are) best furry communities, this is more of a general overview, so, there’s a good chance that we won’t cover a community that takes your fancy as much.

Where Can I Find Them?

With that in mind, there are plenty of places you can find furry communities for yourself if you aren’t happy with the list we offer. Websites such as discord.me provide a database of hundreds of thousands of discord servers and categorize them based on their tags. It’s also a great place to advertise your own server, not even necessarily a furry one, if you are trying to build your own community. Pretty much any server with a platinum subscription you can be sure is legit, but you’re here to find the best of the best. Sites like top.gg, discordservers.com and disboard.org all also provide the same service.

Why Should I Join a Furry Discord Server?Meeting New People: With that whole pandemic thing going on, something that has become increasingly difficult is meeting new people, let alone people who share your interests. Furry discord servers (any discord server) essentially puts you in a room with thousands of people who share the exact same interest as you. Given that mainstream media is typically hostile to the furry fandom, furry discord servers provide a safe space to meet new people where you can be pretty sure that you aren’t just being used as the butt of a joke.

Share Your Art: Although sites like Furrafinity and DeviantArt allow you to share your art with others, none of them really allow for live discussion about your art like discord servers do. Sure you can read comments or whatever, but with furry discord servers that typically have a dedicated art channel, users can send any of their art and discuss it, whether it be praise or constructive criticism. It’s a great way to improve your fursona or get inspiration if you are looking to make one.

Take Part in Events: If you are looking for a way to keep up to date on upcoming furry events such as meetups or conventions, then a discord server is perfect for you. With access to thousands of furries, it’s easy to ask for recommendations on events to go to or ask about what to expect from one if you’ve never been.

Look For Contests and Giveaways: Furry contests are few and far apart in non-furry discord servers, which is why furry discord servers are so great. Contests typically boil down to an art or animation contest and can even sometimes have prizes. Better yet, some furry discord servers will occasionally do furry giveaways with prizes like fursuit accessories if that’s something you’re interested in.

Gaming Communities: Sometimes finding the right people to play your favorite games with can be really difficult, luckily discord caters more towards the gaming community than anything. A lot of furry discord servers have a gaming sub-category within them for fellow furries looking to play games with each other.

It’s funny because it’s the Discord logo… but it’s an animal

Illustration by SteamGridDB via SteamGridDB

It’s funny because it’s the Discord logo… but it’s an animal

Illustration by SteamGridDB via SteamGridDB

The Typical Joining Process

Unlike a lot of servers, furry discords are a lot more scrupulous with who they let in. Thanks to their extreme marginalization by mainstream media, they can get quite a bit of hate. Because of this, a lot of servers will go through a similar process to verify your furriness.

- You’ll be asked to click some sort of verification button that begins an invisible timer on the joining process

- After clicking the verification button you will likely be DM’d an automated response with several prompts like “What is your fursona name?”, “How old are you?” , “How specifically did you find our server?” etc.

- Once you have answered the prompts, your entry to the server will be reviewed by one of the server staff who will ask a follow up question like “Why are you looking to join the server?”.

- Once this is answered, the staff will decide whether or not they should let you in, and given you’re not blatantly trolling, they will let you in to the server.

Sidenote, many servers have an introduction channel where you can introduce yourself to other members while you wait for your request to join the server to be reviewed. Now, let’s get into the list.

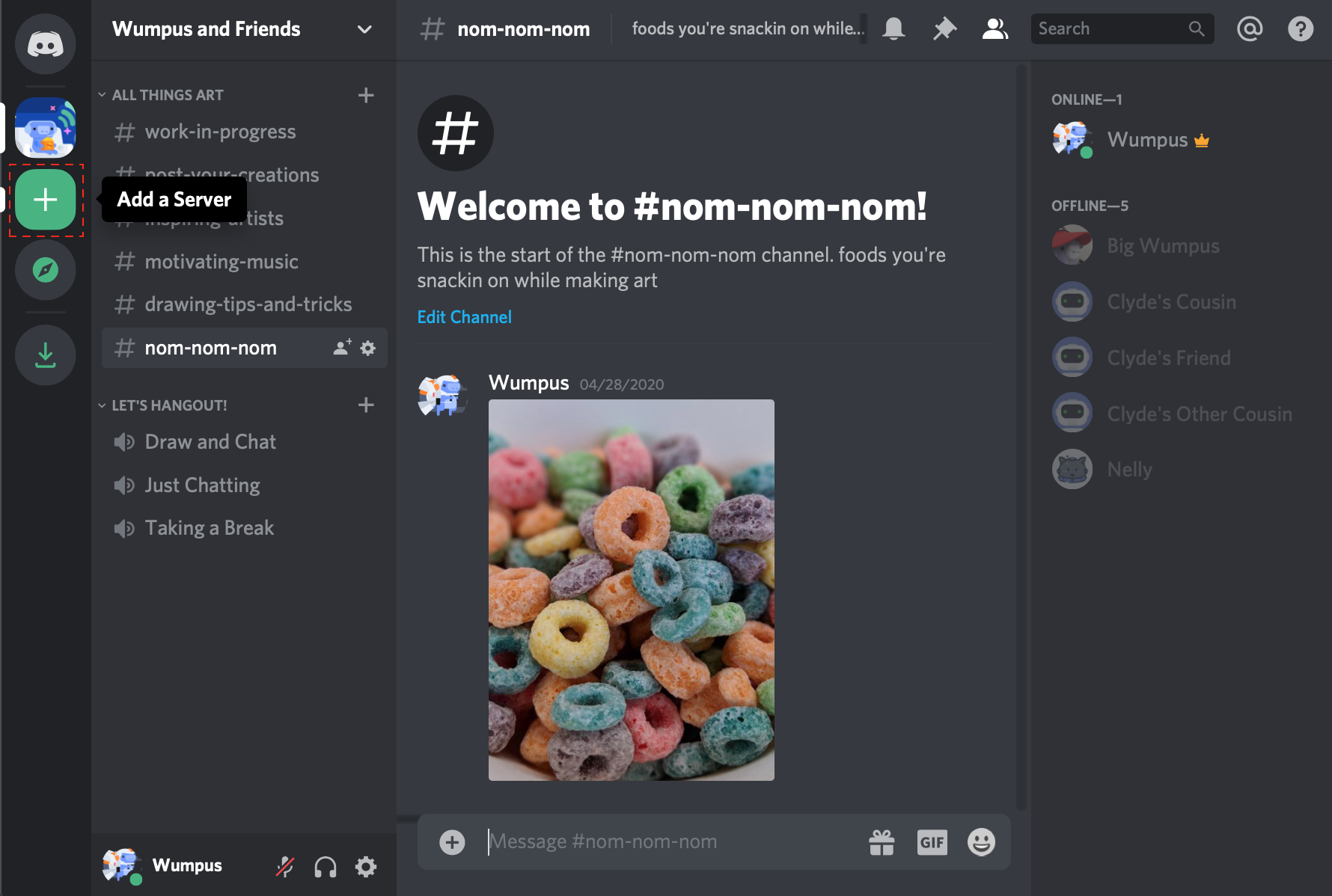

An Empty Discord Server

An Empty Discord Server  Image by Discord via Discord

Image by Discord via Discord

If you, like me, don’t want to spend hours waiting for verification to get into a server, then Paradox Paws is perfect for you. They are a lot more lenient with their verification process while maintaining a non-toxic community that is pretty welcoming even if you are unsure how you feel about the furry fandom. Some members in the server aren’t even furries but just supporters of the community! This makes the server great if you are new to the furry fandom as there is no elitism about how long you have spent in it.

Looking for a movie or games night? Paradox Paws has your back with their weekly games and movie night.

Also, if you are looking for a furry gaming community, then look not further, as Paradox Paws put a huge emphasis on its gaming community, more specifically, Minecraft and Pokemon. They even have a dedicated Minecraft server!

Planet Floof is one of the few furry discord servers that is explicitly SFW… I mean seriously, they do not tolerate NSFW content. Anything from yiff porn to naked furries will result in an almost immediate ban on this server. This makes it perfect for the younger furry audience who are still looking to meet other furries. As well as this, like most furry discord servers, there is a large emphasis on LGBT and gender positivity in this server, xenophobia is not tolerated.

They also have an art advertising channel for furry artists looking to self-promote or network themselves and since they are SFW only, you don’t have to worry about furry porn in the art channel. This also doubles as an opportunity for furries looking to commission someone to make a piece for them to get in direct contact with their artist.

Much like Paradox Paws, they don’t have a particularly grueling verification process either, you simply have to explain what was appealing about the server to you and whether or not you are a furry. Of course they are less likely to let you in if you aren’t a furry, but they are pretty welcoming regardless.

If you’re a Discord Nitro user, Furr Cafe has some of my favorite custom emotes including some great animated ones. Also, Thanks to their dedicated roleplaying channel, this server is great for any furries who’ve been looking for a safe space to roleplay with hundreds of others. Or, if that doesn’t tickle your fancy, this server has a pokemon bot… you can literally play pokemon on discord with this bot. Pokemon will randomly appear in the text channel and the first person to type the catch command can catch it. You can battle other furries with your teams and trade pokemon, it’s really cool.

The staff in this server are really helpful as well, joining a new server can be a bit confusing but if you just ask, they are quite often happy to help with any issues you’re having. Some of the members are even musicians and

Furry Forest is one of the less safe for work entries on this list due to its NSFW art channels. It’s also one of the smaller communities but they describe themselves as an environment “away from the chaos of other fur servers” and that they are. With only 600 people, this server is much quieter compared to the previous three and entry into the server isn’t really difficult at all.

They’re also pretty frequent with art giveaways for members who are willing to invite a friend as entry into the giveaway!

Furr Cafe Server Icon

Illustration by Furr Cafe via Discord.me

Furr Cafe Server Icon

Illustration by Furr Cafe via Discord.me

This one was tricky because it was (from what I found) the hardest server to get into. However, this difficulty is not without reason, they claim to have, and I’m still not entirely sure how this works, a “Zero-Raider Entry System”. Regardless of whatever Tony Stark technology they have running behind the scenes on this server, it is the safest space for furries and non-furries alike to express their interest. Furry servers, more than any other discord servers, get raided like crazy whether it be homophobic or transphobic attacks. There is an absolute zero-tolerance policy on top of the scrupulous verification that you have to go through. If you’re looking for a safe place to hunker down and just let your hair loose on discord, West’s Haven is your best bet.

They even have personalized roles, an art channel, a dedicated events team, and a “no-drama guarantee”.

How Do I Start My Own Furry Discord Server?

Starting a discord server of your own is the easy part. Growing a community of your own however can be a bit more challenging. If you are looking to start a large community like the ones listed above, you need one of two things: pre-existing clout or a good reason for people to join. Here’s some steps you can take to start building the server.

- Before you do anything, make the server look presentable. Make dedicated text channels, verification bots, automatic role-assignment, the full works!

- The less professional a server looks, unless it’s a server for friends, the less likely people are to stay on it

- Create quirky roles that give people a sense of progression and welcoming into the server. Some servers allow users to climb up the ranks depending on their activity in it.

- Start inviting people. This could be your friends or people you know may be interested.

- If you’re struggling to find people to invite, consider checking out furry subreddits or other social media to see if you can spark any interest there. Hopefully these people can start some initial buzz; encourage them to invite friends of their own.

- Assign people you know you can trust to moderate the server, you’re gonna need it. There’s a good chance the server could get raided and trolled so it’s key to have people on at all times who can handle that sort of thing

- While this is optional, if your server is getting traction, you should consider some paid advertisement on sites like discord.me as if your server has a growing and active community, people looking for furry communities will feel more inclined to join.

- Also, if you do decide to advertise on these sites, make sure you are marking your server with relevant keywords such as “furry” or “yiff” as it gives it a better chance of being found by users.

- Host weekly or even daily events. This can be a giveaway, a competition, movie nights, gaming sessions, anything you wish really. As long as it keeps the users of the server engaged, it should be alright. This is to maintain activity on the server.

Of course this isn’t a guaranteed route to success, luck will always play a big factor on whether or not your community is thriving, but those are just some of the steps you can take to increase your chances of success greatly.

West’s Haven Logo

Illustration by West’s Haven via Discord.me

West’s Haven Logo

Illustration by West’s Haven via Discord.me

Are There Any Discord Alternatives?

If, for some reason, you have no interest in using Discord, there are several text-based communities out there that are equally if not bigger than some of the aforementioned Discord servers. Social media like twitter, reddit, even VRChat, has some great furry communities. Here’s just a few of the furry communities in each.

Reddit: Let’s just get the easiest and most obvious out of the way, r/furry is one of the largest furry subreddits that you can find. It has around 270,000 members as of the publication of this article and is predominantly used to share and discuss furry art. Then there is r/fursuit, with about 20,000 members, it’s a community for furries to share and discuss their fursuits. If you’re looking for something a little more explicit, one of the biggest furry porn subreddits is r/yiff, where around 300,000 members can share their furry porn. If you’re struggling to find suitable subreddits to post to, consider checking out this article on the best reddit communities for furries for some inspiration.

Twitter: While its often joked that twitter is just a toxic cesspit, you can find some really loveable people on there. Some good users to follow if you’re looking for safe furry communities on twitter would firstly have to be Furry Valley. They have their own Discord server and telegram if that tickles your fancy. They have a big gaming community under their belt as well, more specifically Animal Crossing, Pokemon and Rainbow Six Siege. Also, Furs Of Color serves a more specific purpose because, as you could probably guess, it’s a community for furries who are also people of color. It does the same thing as pretty much any twitter community, but is specifically inclusive of people of color.

VRChat: This is an exciting one to discuss because things start to get really interesting. Although VRChat is less accessible to those who don’t have a PC and such, some of the communities on this game are just buzzing with personality. Firstly, there is TailBass which is a virtual dance coordination group that has live furry DJs playing in VRChat. If that isn’t brilliant enough, they created an event called HexFurryfest, which is a virtual furry rave that takes place two times a year. There’s also RubberDragonLabs which a bit more on the NSFW side of VRChat as its a community centered around the artwork of Jackie Demon who depicts a rubber species of furry, in… let’s just say… compromising positions.

Now go and join a furry community and explore this beautiful, furry world!

The post The 5 Best Furry Discord Servers appeared first on Fursonafy.

The illicit allure of Smokey Bear, US Forest Service mascot

The annual Ursa Major Awards are open — Vote now for the fandom’s favorite creations!

Out in the wild, I saw a human sharing some very furry-adjacent news. Suzyn was on a group for paid Slate podcast subscribers, and this story was her suggestion for one they should do. If they wouldn’t, I thought someone should. Thanks to Suzyn for her parts, and I added comments for furry readers.

There was a related Slate story from December 2020: When Did Smokey Bear Get So Hot?

It shows his buff yiffability predates furries. Don’t blame us! Hot anthropomorphic animal people are just nature’s way of showing imagination is healthy. Proof:

When Smokey was a newly-minted mascot, there was a risk to taking this farther. The 1950’s American government, preoccupied with Red Scares, might have forecasted a subversively thirsty fandom and made their love forbidden.

A law passed in 1952 made it ILLEGAL to misuse the image of Smokey Bear. (Not Smokey THE Bear, the Forest Service gets salty about that). You could be JAILED. Here’s the law: 18 U.S. Code § 711 – “Smokey Bear” character or name.

A stiff sentence for yiff

In an omnibus bill passed by Congress in December 2020, this law was repealed for reasons unclear. (If I’m ever forced to testify about furries infiltrating the government, I’ll take the 5th).

This law was why Suzyn noticed Smokey; she personally wouldn’t mess with the government’s intellectual property rights, but it made her curious. She started looking into Smokey and the rules and fandom for him, and found it pretty fun.

First off, the rules for dressing up as Smokey are almost exactly the rules about being a Disney cast member in character at Disney theme parks — as in — they are to a layperson’s eye oddly strict:

Click to access finalsmokeyhandoutsacessibleforweb.pdf

Yes, the government mandates no breaking the magic. They say don’t be a stinker, brush your fur, bring an escort, and no wardrobe malfunctions or impropriety for the shirtless shoveler. It means sirens would go off if he tried to sneak into a furry convention after dark party.

Second, if you want to properly gear up to prevent forest fires, www.smokeybear.com links to a shovelful of Official Smokey Bear Licensees and Products.

For $2499 plus a $635 cooling system, there’s a full Smokey costume from pro mascot supplier Facemakers Inc. (“Sold ONLY to US and Canadian Foresters.”) If you can pony up 11 grand, Robotronics has an animated RoBear. There’s also an 8-foot inflatable costume from Signs & Shapes International.

Third, he was a real bear and in the 1950’s was so cool he needed a zipcode for his fan mail, something that may not even be true for Elvis.

The brawny hunk-a burnin’ love starred in many ads, TV and radio guest spots with celebrity hosts like Bing Crosby. There’s a decade-by-decade timeline with many of them.

Fourth, if your dream guest is Betty White, you’re in luck.

The history of Smokey Bear, the other celebrities who have appeared in ads with Smokey Bear, the “Smokey Bear effect” and, um, youtube fan videos where he fights McGruff are all out there.

Obviously, there’s a huge rabbit hole of weird. If you make videos, or have a podcast, a LOT of it is audio friendly and there may be some park rangers who would love to talk to you!

If you enjoyed this, you’ll probably enjoy this podcast — technically about Woodsy the Owl — but it discusses all those odd laws that also covered Smokey. (February 23, 2021): UnderUnderstood — Give a Hoot, Don’t Pollute.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon. Want to get involved? Try these subreddits: r/furrydiscuss for news or r/waginheaven for the best of the community. Or send guest writing here. (Content Policy.)

S9 Episode 19 – Kink Club Rub - Join Roo, Sammy, and Klik as they dive into the Furpile and find out why this is not a Test! Fur What It’s Worth has been found with its zipper down! The Admins of the Furry Clubhouse will be whipping you into shape and com

NOW LISTEN!

SHOW NOTES

SPECIAL THANKS

YOU! We run the clubhouse!

PATREON LOVE

The following people have decided this month’s Fur What It’s Worth is worth actual cash! THANK YOU!

Uber Supporters

Sly

Premium Tier Supporters

Jarle, the Spirit Wolf

Get Stickered Tier Supporters

Nuka goes here

Kit, Jake Fox, Nuka (Picture Pending), Ichi Okami

Fancy Supporter Tier

Rifka, the San Francisco Treat and Baldrik and Adilor and Luno

Deluxe Supporters Tier

Guardian Lion and Koru Colt (Yes, him), Ashton Sergal, Harlan Fox

Plus Tier Supporters

Skylos

Snares

Simone Parker

Ausi Kat

Chaphogriff

Lygris

Tomori Boba

Bubblewhip

GW

Moss

McRib Tier Supporters

August Otter

TyR

MUSIC

Opening Theme: RetroSpecter – Cloud Fields (RetroSpecter Mix). USA: Unpublished, 2018. ©2011-2018 Fur What It’s Worth. Based on Fredrik Miller – Cloud Fields (Century Mix). USA: Bandcamp, 2011. ©2011 Fur What It’s Worth. (Buy a copy here – support your fellow furs!)

Break: Mystery Skulls – Ghost. USA: Warner Bros Records, 2011. Used with permission.

Closing Theme: RetroSpecter – Cloud Fields (RetroSpecter Chill Mix). USA: Unpublished, 2018. ©2011-2018 Fur What It’s Worth. Based on Fredrik Miller – Cloud Fields (Chill Out Mix). USA: Bandcamp, 2011. ©2011 Fur What It’s Worth. (Buy a copy here – support your fellow furs!) S9 Episode 19 – Kink Club Rub - Join Roo, Sammy, and Klik as they dive into the Furpile and find out why this is not a Test! Fur What It’s Worth has been found with its zipper down! The Admins of the Furry Clubhouse will be whipping you into shape and com

TigerTails Radio - Episode 1000 Gunge Highlights

Now that Season 13 has completed and the show is off air for a few weeks while upgrades are done and things are reassembled, let's have a look back to one of the pre-recorded sections of Episode 1000 at some of the times pies and gunge went flying in the studio, either for fun or for charity. Music from YouTube's library. Thumbnail/Title Card artwork by Zodd: https://www.furaffinity.net/user/zodd95/

Breaking Up Is Hard To Do

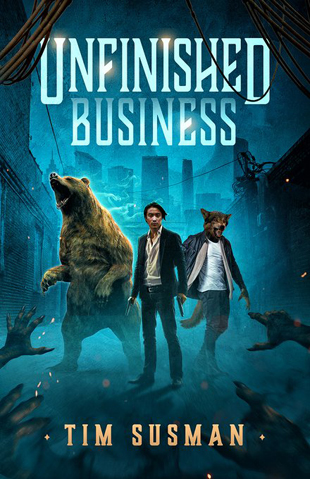

Getting ahead of the curve with a new fantasy/horror/mystery novel coming later this year from writer Tim Susman: Unfinished Business. “Private Investigator Jae Kim doesn’t have a werewolf problem – at least not as long as he can keep clear of his ex-boyfriend Czoltan. But when a suspicious police report hits the streets of Wolftown, Jae suddenly finds himself hunted on the streets he used to freely roam. Dodging bullets from Wolftown vigilantes, he’s stuck hiding out with Czoltan while he and his were-bear ghost Sergei search out whoever set him up – and his life isn’t the only one at stake.” Look for it this July from Argyll.

image c. 2022 Argyll Productions

Species Dysphoria

I’ve heard of this term "species dysphoria." Is this a valid term? I sometimes feel like I’m just going crazy, but I still just don’t know what I am. There are days I feel like I am a human being, but there are days where I just don’t. It stresses me. I hope my best friend doesn’t judge me for it. I have a very good feeling he wouldn’t; he’s always a very open-minded person and a huge sweetheart. But I’m scared about the chance of him rejecting my possible identities. However, I do remember we talked about how there are so many things in this world we probably don’t know the truth to and probably never will, and he explain that he does believe that maybe it can be possible for someone to be some kind of therian deep within their being. So, I do know he’s a very open-minded person.

I am in my 20s now. I turned 20 recently. I feel like my body has been going through so many strange feelings. I always try not to think about the worst-case scenario, but it’s hard.

I just worry I’m going crazy. I want to talk to my therapist about it, but I’m worried she’ll misconstrue [this].

Maxi

* * *

Dear Maxi,

There is, indeed, such a thing as species dysphoria (called Species Identity Disorder among mental health professionals), the feeling that you are inhabiting a body that is the wrong species. Are you familiar with otherkin? Otherkin are those who feel, for one reason or another, they are not human. This can mean they feel "other" in a spiritual/psychological sense or that they are actually, physically different but are concealing their true form under a human guise. I have met otherkin who believe they are from another world that faced some kind of cataclysm and they had to come here and take human shape in order to survive. Others believe they come from another dimension or that they are of an angelic or demonic origin. Some of these otherkin are in an animal form, some are more like a species of elf or other humanoid (but not human) race.

Species dysphoria is comparable in some ways to sex dysphoria (often incorrectly, in my opinion, called Gender Identity Disorder since "gender" just refers to social standards of what is "male" and "female" while "sex" is biological) in that both involve feeling that your physical form does not match who you truly are. It is interesting that psychologists are coming to accept sexual dysphoria as a real thing, but species dysphoria is regarded as a type of mental illness. But I have to ask, if one can feel that they are, say, a woman in a male body, why can't one feel as though they are, again as an example, a lion or a dragon in a human body? (Unfortunately, while surgery can replace male parts with something simulating female anatomy, the same is not true for turning someone into another animal--just don't watch the horror movie Tusk.)

In "Furries from A to Z (Anthropomorphism to Zoomorphism)" by Kathleen Gerbasi et al, published in the journal Society and Animals (August 2008), the authors surveyed over 200 furries at a convention and found that nearly half (46%) had, to a lesser or greater extent, some feeling that they were not entirely human. This coincides fairly well with my experience with furries in that about half of them feel they are furry while the other half are hobbyists and are just doing this for fun (in the same way as a Trekkie might dress up as a Vulcan at a Star Trek convention but never considers themselves to be an actual Vulcan).

So why do many furries feel this way? There are a couple of possibilities, and I will just touch on them here (this could be a book, seriously). One possibility is social. Many furries feel rejected by (or reject) humanity and their own humanness, which leaves them feeling disconnected to the extent that they literally do not wish to be human. When one feels this way intensely and long enough, it can become ingrained in your very being. Another possibility depends on whether or not you feel reincarnation is possible and, perhaps, furries with species dysphoria are recalling former lives as some type of animal (or even alien species). The third possibility has to do with empathy: a deep connection with another animal, one so intense that it begins to fill one's own being. This is kind of how I feel about bears. I feel very connected to these beautiful and majestic animals, almost feeling like they are a part of me.

Or, we could just be crazy.

But I don't think it's that last one. The definition of "crazy" to me means that our perception does not match reality. But if the reality is that we are deeply connected to another species, are we truly crazy? No. No, I don't believe that. Also, if we are really crazy, it would make it impossible to function in this world.

This all keys into a core belief of mine: we are not our bodies. Even many "mainstream" humans believe this. They believe we are our "soul." But our soul or spirit or essence or ego is not the same thing as our flesh. Our flesh is just something we use to travel around in this reality. The spirit that is within us is connected to all spirit that inhabits this universe. Truly, we should not limit ourselves to thinking that we are just Homo sapiens. That is just a species. You know what I think? I think many furries (and others who don't know about furries or are connected in other ways) have freed themselves of the constraints of species and open themselves up to an interconnectedness with all creatures and spirits.

Don't let it "stress" you if sometimes you don't "feel human." That's just you reaching outside of your physical limitations. That's just you stretching your spirit and embracing the life that is all around you. Just like a man who refuses to let society say they can't wear a dress or makeup if they choose to, you are rejecting having others impose upon you their standards of what you should look and feel like.

Bottom line: you are not crazy. You're merely struggling with trying to live up to the limitations imposed upon you by our neurotic society that insists on making everyone look and act like we are all the same.

But we are not all the same, are we? Instead of fretting about it, embrace it, explore this otherness you are feeling. You can still do that and function within our lame society. You can attend class or go to work with your human persona firmly in place, but when you have a quiet moment to yourself, you can explore outside your physical self and the rigid standards of humanity. What's cool is that you have an entire furry community that you can talk to about it and who won't call you crazy because we sympathize and empathize with you.

Hope that makes you feel better.

Hugs,

Papabear

Bearly Furcasting S2E45 - 100th Episode! Explosions, Math, Trivia, and Mayhem!

MOOBARKFLUFF! Click here to send us a comment or message about the show!

Moobarkfluff! This is our 100th published episode and we had no idea! LOL. Bearly and Taebyn chat about mostly normal things, we have a liars paradox, Taebyn shares a new 'song', many awards are discussed and of course we pepper our show with bad jokes and puns. We apologize for our lousy Italian accents. Join us for a regular ol' episode won't you? Moobarkfluff!

https://www.bonfire.com/store/bearly-furcasting/

Thanks to all our listeners and to our staff: Bearly Normal, Rayne Raccoon, Taebyn, Cheetaro, TickTock, and Ziggy the Meme Weasel.

You can send us a message on Telegram at BFFT Chat, or via email at: bearlyfurcasting@gmail.com

Vote for the 2021 Ursa Major Awards

Voting has opened for the Ursa Major Awards, this time celebrating the best in anthropomorphic stories, movies, comics, art, and more from the year 2021. Modeled on the Hugo Awards (given annually by the World Science Fiction Society), the Ursa Major Awards give furry fans around the world a chance to celebrate their favorite “furry things” from any of 14 categories. For instance: This year’s nominees for “Best Anthropomorphic Motion Picture of 2021” include Pixar’s Luca, Netflix’ My Little Pony: A New Generation, Disney’s Raya and the Last Dragon, Illumination’s Sing 2, and Sony Animation’s Wish Dragon. And that’s just one category! Visit the official web site to register and vote (and maybe donate a little if you’re feeling generous — it’s a not-for-profit operation!). But hurry up! Voting closes at the end of this month.

image c. 2022 ALAA

Dogs and Cats Reading Together

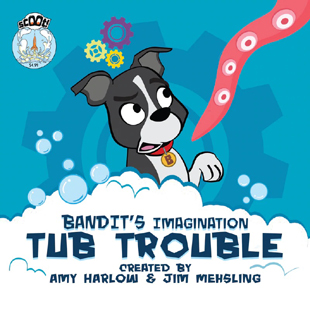

Scout Comics have an imprint called the Launch Series, which is designed for the youngest of beginning readers. To quote them, “Launch bridges the gap between children’s picture books and comics”. Following a long-honored tradition, of course the effort involves funny animals — chief among them, dogs and cats. First up are the adventures of Bandit the Boston Terrier, in a series of softcover books written by Amy Harlow and illustrated by Jim Mehsling. “Bandit is a spunky Boston Terrier with a wild imagination. Bandit’s best friend, Daisy, is a jolly and somewhat lazy Boston Terrier. Follow their adventures as Bandit confronts his household nemesis, the vacuum cleaner.” Then there’s the Supercats series, written by Caleb Thusat and illustrated by Angela Oddling. “In this origin story we see the young Mewow, destined to become a supercat, in her first adventure she taps into the hero within to save innocents in trouble… because Supercats will always save the day!” Both series have several titles.

image c. 2022 Scout Comics

FWG Monthly Newsletter: March 2022

The end of February has proven to be a very scary one for a lot of people. From everyone here at the Furry Writers Guild, we hope everyone is able to stay safe – whether it be from war, the continued pandemic, or natural disasters. We hope that you’re able to escape to your writing if possible, but also know that it’s ok to step back from it all if you’re feeling overwhelmed. Find your solace and peace however you may.

In the furry writing world, March brings us towards the business end of award season. The finalists for the Ursa Major Awards should be announced soon (if not already), and the Coyotl Awards have just two weeks of nominations left. Both of these awards will then be open for voting on the finalists (with the Coyotls being open only to FWG members). We encourage everyone to get involved and vote for your favourites.

March will also see the Furry Writers Guild start preparing for the guild elections in April. Should anyone wish to put themselves forward for any of the guild officer positions, then please do so in the appropriate area of the forums. An election date has not yet been called, so feel free to take a few weeks to weigh up your position and goals should you put yourself forward.

As of this stage, I am unsure whether I will be standing for president again, due to a changed work situation.

There are a few ongoing submission calls for short stories, though we have not seen many themed anthology calls at this stage. If you see something that you think can be highlighted by the FWG, then please contact us with information about it!

FURVOR #1 – Deadline Around March

Prehistories – Deadline March 31st

Isekai Me! – Deadline When Full

Children Of The Night – Deadline When Full

#ohmurr! – Deadline: Ongoing

Zooscape – Reoccurring submission period.

Please also consider checking out some of the new and upcoming releases from our members.

C.A.T.S.: Cycling Across Time And Space: 11 Feminist Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories about Bicycling and Cats – an anthology featuring guild member Alice Dryden. Released February 8th 2022.

Brothers At Arms, by R.A. Meenan. Released February 14th, 2022.

Scars of the Golden Dancer, by NightEyes DaySpring. Available for pre-order. Released March 4th.

Knotty Works, by NightEyes DaySpring. Available for pre-order. Released March 4th.

Aces High, by J. Daniel Phillips. Available for pre-order. Released March 18th.

A Furry Faux Paw, by Jessica Kara. Available for pre-order. Released May 24th 2022.

Red Pandamonium, by Roan Rosser. Available for pre-order. Released June 13th 2022.

Unfinished Business, by Tim Susman. Available for pre-order. Released July 5th 2022.

As always, any guild members who want to see their upcoming books included in the newsletter, please let us know! We try to keep up to date with everything, but there will always be some things we miss.

Once again, we hope everyone is able to stay safe. If you feel comfortable writing, then we hope you can gain some degree of peace and escape from it. If you can’t, please don’t feel guilty that there are higher priorities.

Until next month.

Happy writing and stay safe.

J.F.R. Coates

FWG Monthly Newsletter: March 2022

The end of February has proven to be a very scary one for a lot of people. From everyone here at the Furry Writers Guild, we hope everyone is able to stay safe – whether it be from war, the continued pandemic, or natural disasters. We hope that you’re able to escape to your writing if possible, but also know that it’s ok to step back from it all if you’re feeling overwhelmed. Find your solace and peace however you may.

In the furry writing world, March brings us towards the business end of award season. The finalists for the Ursa Major Awards should be announced soon (if not already), and the Coyotl Awards have just two weeks of nominations left. Both of these awards will then be open for voting on the finalists (with the Coyotls being open only to FWG members). We encourage everyone to get involved and vote for your favourites.

March will also see the Furry Writers Guild start preparing for the guild elections in April. Should anyone wish to put themselves forward for any of the guild officer positions, then please do so in the appropriate area of the forums. An election date has not yet been called, so feel free to take a few weeks to weigh up your position and goals should you put yourself forward.

As of this stage, I am unsure whether I will be standing for president again, due to a changed work situation.

There are a few ongoing submission calls for short stories, though we have not seen many themed anthology calls at this stage. If you see something that you think can be highlighted by the FWG, then please contact us with information about it!

FURVOR #1 – Deadline Around March

Prehistories – Deadline March 31st

Isekai Me! – Deadline When Full

Children Of The Night – Deadline When Full

#ohmurr! – Deadline: Ongoing

Zooscape – Reoccurring submission period.

Please also consider checking out some of the new and upcoming releases from our members.

C.A.T.S.: Cycling Across Time And Space: 11 Feminist Science Fiction and Fantasy Stories about Bicycling and Cats – an anthology featuring guild member Alice Dryden. Released February 8th 2022.

Brothers At Arms, by R.A. Meenan. Released February 14th, 2022.

Scars of the Golden Dancer, by NightEyes DaySpring. Available for pre-order. Released March 4th.

Knotty Works, by NightEyes DaySpring. Available for pre-order. Released March 4th.

A Furry Faux Paw, by Jessica Kara. Available for pre-order. Released May 24th 2022.

Red Pandamonium, by Roan Rosser. Available for pre-order. Released June 13th 2022.

Unfinished Business, by Tim Susman. Available for pre-order. Released July 5th 2022.

As always, any guild members who want to see their upcoming books included in the newsletter, please let us know! We try to keep up to date with everything, but there will always be some things we miss.

Once again, we hope everyone is able to stay safe. If you feel comfortable writing, then we hope you can gain some degree of peace and escape from it. If you can’t, please don’t feel guilty that there are higher priorities.

Until next month.

Happy writing and stay safe.

J.F.R. Coates

Grovel Reports March 1st 2022 - Furry Convention News Abroad

Hi everyone, there are a lot of updates from conventions locally and abroad so this will be a summary: WUFF (UAFurence) https://twitter.com/uafurence Link to Furry Ukraine Artists https://www.furaffinity.net/journal/10138995 StratosFur has opened PreReg https://stratosfur.org/blast-off-with-us/ Board of Anthropomorphic Representatives: Colorado https://twitter.com/justboiler/status/1494466079871152131?s=20&t=WZ89TNrDA8Y4D5rnmSmrDw Furvana https://twitter.com/FurvanaNW SpokAnthro https://twitter.com/SpokAnthro/status/1495249790514253824?s=20&t=2gUb14UQBGfDDYeRa5bcLw Golden State Fur Con https://gsfurcon.com/ HMHF or Harvest Moon Howl Fest https://twitter.com/HMHowlFest/status/1498357772517261319?s=20&t=WZ89TNrDA8Y4D5rnmSmrDw Furry Takeover https://www.furrytakeover.com/ CanFURence https://canfurence.ca/registration/ Ursa Major awards 2021 https://ursamajorawards.org/voting2021/ Weekend Furry Retreat https://twitter.com/wkndfurretreat Artwork at end of video was retweeted from ToasterFox https://twitter.com/Toaster_Fox/status/1498167688316653575?s=20&t=LrQE0uWtHZXxwLDQzyiTdQ If you like the work I do please like/follow/share to support the channel I'm on multiple platforms https://twitter.com/GrovelHusky https://www.twitch.tv/grovelhusky https://t.me/grovelreports Subscribe to show support https://www.youtube.com/c/GrovelHusky/?sub_confirmation=1 Grovel Reports Studio made by Kydek https://twitter.com/FluffyKydek Banners used in the channel were made by Slushi https://twitter.com/Slushi3Brushi3?s=09 Music created for Grovel Husky by Whooshagg https://whooshagg.com/ Grovel Reports March 1st 2022 - Furry Convention News Abroad #furryfandom #furry #furryconvention

Watch The Skies!

Wow, the things you miss if you blink… Things like Carriers, a new full-color comic series from Red 5 Comics. “Fable, Gladius, Cherrybomb, Dark Dove: No one has heard of these brave heroes… yet… but they are the only thing standing between the citizens of New York and the unseen terrors that lurk all around them. A band of weaponized carrier pigeons, they soar the night sky looking for new threats and find their largest one yet when the Croc King comes climbing up out of the New York sewer!” See? It’s written by Ben Ferrari and Erica J. Heflin, with art by Jim O’Riley (no relation!) and Elias Martin.

image c. 2022 Red 5 Comics

Gdakon will offer Ukranian attendees full ticket and hotel booking refunds

Gdakon将为乌克兰与会者提供全额门票和酒店预订退款

The Spectacular Rise of Infurnity + More About Taiwanese Furs Feat. J.C. [FABP E19]

The Spectacular Rise of Infurnity + More About Taiwanese Furs Feat. J.C., Fox and Burger Podcast Episode 19. ---- We sure do love Taiwan! Because for this month’s episode, we’re going back to the Heart of Asia. Our guest of honor today has been someone on our list for a very, very long time. He’s yellow, he’s a cat - you guessed it, it’s J.C. the yellow cat from Taiwan. J.C. has been in the fandom for almost 20 years and is the current con chair of Infurnity, the largest fur con here in Taiwan. In this episode, we asked him questions about Infurnity and Taiwanese furries overall, plus we featured some questions from you guys, the audience. Let’s give a big meow for J.C.! Correction: The website that J.C. mentioned at 04:23 is actually https://fanart.lionking.org/ ---- Timestamps: 00:00 Section 1: Introduction 00:00 Podcast intro 02:00 Guest introduction 06:07 Section 2: JC and Infurnity 06:14 Growth of Infurnity, and challenges along the way 08:36 Not enough attendees for a fur con? 10:32 What makes Infurnity stand out from other cons? 16:00 Have you ever imagined running a con for 7 years? 17:55 Pros/cons of hosting an online con 21:23 What’s the next goal for Infurnity? 24:23 Section 3: Comparing and Contrasting Fandoms 24:37 How would you describe Taiwanese furs overall? 26:30 Does culture have an affect on how Taiwanese furries act? 29:23 Biggest difference between American and Taiwanese furries? 31:42 Is Taiwan influenced by the Japanese fandom or the Western fandom? 34:34 Ray Q1: What were the early days of Infurnity like? 40:20 Ray Q2: What prompted your journey in the fandom? ---- Social Media: Official FABP Twitter: https://twitter.com/foxandburger Matcha Fox: https://twitter.com/foxnakh https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK9xoFQrxFTNPMjmXfUg2cg Burger: https://twitter.com/L1ghtningRunner http://www.youtube.com/c/LightningRunner JC: https://twitter.com/jcdump https://www.facebook.com/jcdump Official Infurnity Twitter: https://twitter.com/infurnity Ask the Con Chairs Panel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Gzg6vyYoA3c ---- Footage Credit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8Bcg8OsOtw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2sf5XbqLza8 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgX6_WeLIzs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QGO0IxYSHCw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahh_YbMBNVg https://zh.wikifur.com/w/index.php?title=%E9%87%8E%E6%80%A7%E7%96%86%E7%95%8C&variant=zh-tw http://wolfbbs.net/showthread.php/11182 https://www.beastfantasia.com/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Y8Bcg8OsOtw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XP5lz2CYNR4 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=afBI2icz7v0 https://www.furaffinity.net/view/35949508/ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jl56QRAcqYI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ToFBcQbRovw https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VgX6_WeLIzs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5Bmp2z89vI https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f8wbCkvzRac https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mVCXd97OV98 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sidNKV4JXAA https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=AzTB9feYo6s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2U25fQ3dq3s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ahh_YbMBNVg Other pictures and video provided by J.C., Pixabay, and hosts' personal footage. Intro/Outro Music: Aioli by Andrew Langdon. ---- The Fox and Burger Podcast is one segment of our production house, Fox and Burger Productions. The podcast’s goal is twofold: 1, to know more about the Asian furry fandom; and 2, compare and contrast the Asian fandom with the Western one. If you have a guest that you would like to interview, please PM us! We will also take questions for our guests, so don’t miss this opportunity to know some amazing furs.

German Furs in Taiwan? Beer, Bread, and Baozi - February Livestream

German Furs in Taiwan? Beer, Bread, and Baozi - February Livestream ---- In our second livestream ever, we invited three German furs who have been to Taiwan before to share with us their experiences here. Our guests for this livestream were Streifi, Azurfox, and Parca! All have been to Taiwan before as well as Infurnity. The goal of our live streams is to ask questions that are an extension of the podcast. Using a more free-form format, we focus on broader topics not limited to Asia. We also want to use this format to better engage with our audience. We sincerely appreciate everyone’s questions as interactions during the stream. Let’s explore the furry fandom together! ---- Social media: Our official Twitter: https://twitter.com/foxandburger Matcha Fox: https://twitter.com/foxnakh https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCK9xoFQrxFTNPMjmXfUg2cg Burger: https://twitter.com/L1ghtningRunner Streifi: https://twitter.com/StreifiGreif Parca: https://twitter.com/parcatheorca

There is Puppetry in my Neighborhood

We had not heard about this, but we should probably mention it now! Animation World Network just reported that PBS Kids has secured some really big grants to help fund new TV series created by Fred Rogers Productions (named after the late great creator of Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood, of course). And at least one of those series is of note to furry fans: “Inspired by the funny, quirky side of children’s television pioneer Fred Rogers, Donkey Hodie is an imaginative puppet series following the adventures of Donkey Hodie, an enthusiastic and charming go-getter who takes on each day with curiosity and resilience, and her pals Purple Panda, Duck Duck, and Bob Dog. Set in the whimsical land of Someplace Else, the social-emotional series is designed to empower children ages 3-5 to dream big and overcome obstacles in their own lives, to work hard and persevere in the face of failure, to be resourceful and discover they can solve problems on their own — and to laugh themselves silly along the way.”

image c. 2022 Fred Rogers Productions

Bearly Furcasting S2E44 - Guest Host Path Hyena, Transfurmation Station

MOOBARKFLUFF! Click here to send us a comment or message about the show!

Moobarkfluff!

This week while Bearly is away, special guest host Path Hyena joins us for an off the rails super-sized show chock full of laughs. We have some fun when Ski Sharp visits with us on Five Minute Furs For Fun. Grubbs Grizzly stops buy to chat about his new publishing company and this year's Good Furry Awards. Taebyn has a hot time with Lux at the Transfurmation Station. Taebyn and Path perform a dramatic reading of the show notes. We take a detour to story time to visit with Frog and Toad and learn all about willpower. Then, Taebyn and Path try to see who tells the worst jokes. You don't want to miss a second of this week's thrilling episode!!!

Moobarkfluff!

https://www.bonfire.com/store/bearly-furcasting/

Thanks to all our listeners and to our staff: Bearly Normal, Rayne Raccoon, Taebyn, Cheetaro, TickTock, and Ziggy the Meme Weasel.

You can send us a message on Telegram at BFFT Chat, or via email at: bearlyfurcasting@gmail.com