Feed aggregator

Kaar Solo 08 - Sharking tuesday!

Dragget MD #6: Zuckin' Passion - please support us on Patreon! -- www.patreon.com/…

please support us on Patreon! -- www.patreon.com/thedraggetshow http://www.youtube.com/draggetshow http://www.twitch.tv/draggetshow for all things Dragget Show -- www.draggetshow.com Dragget MD #6: Zuckin' Passion - please support us on Patreon! -- www.patreon.com/…

Black History Month Spotlight: Jakebe T. Lope

It’s February, and in honor of Black History Month we have been featuring some of the black authors that are members of the Furry Writers’ Guild. Today will be our last feature for the month, and we will be sharing an interview done with Jakebe T. Lope! He has had stories featured in Breaking the Ice: Stories from New Tibet, Historimorphs, and New Fables. Without further ado, let’s get to the interview.

—

FWG: Tell the guild and our readers a bit about yourself.

Jakebe: My name is Jakebe T. Lope, though I’ve gone by others in my day. I’ve been in the furry fandom since 1996, so I’m pretty sure that makes me a greymuzzle! I’m a long-time writer and blogger — my blog “From the Writing Desk” is a collection of personal essays about the writing process, my journey with mental health, the furry fandom, Afrofuturism, Buddhism, and politics. Currently, I’m writing serialized erotic fiction through Patreon under The Jackalope Serial Company.

FWG: What is your favorite work that you have written?

Jakebe: I’m really happy with “Nightswimming”, the short story I wrote for Breaking The Ice. It was my first published short story, and I really tried to stretch myself to capture the feeling of isolation within New Tibet and what would make anyone want to stay on that frozen hellhole.

I think the writing that means the most to me, though, are the essays I’ve written about mental health on From The Writing Desk. I come from a background with a serious stigma attached to mental health issues, and it means a lot to me to be open and honest about it, and help others who might be struggling with similar issues.

FWG: What do you think makes a good story?

Jakebe: I think any good story has to end with its reader feeling better about the world they’re living in. Even the stories designed to make us uncomfortable are guides for us to pay attention and work with that discomfort so we’re better able to deal with it on the other side. That doesn’t mean a story can’t just be dumb fun, but even light entertainment needs to leave us with the feeling that the world is a rad place, or it could be if we worked for what we believe in.

It’s really hard to do this without browbeating an audience with some message. I think you need to be honest, fearless, and compassionate in order to achieve it. The best writing fosters that sense of instant, empathetic connection.

FWG: How long have you been in the guild, and what changes have you seen with regards to how writing is handled since joining?

Jakebe: Oh man, I’ve been in the guild for a while — so long I can’t remember when I’ve joined. I think writing has been largely democratized since I’ve joined, and it’s wonderful to see so many new perspectives popping up across the fandom, with so many interesting expressions of what brings us to it. It’s been really encouraging to see.

At the same time, I worry that there’s been a breakdown of the writing community because we’ve stopped listening to each other and become much more ego-driven. In my experience, there’s been less of a willingness to help one another with our craft and the realities of the market. I’d really like to see us return to a spirit of collaboration, guidance, and respect for the craft.

FWG: What does Black History mean to you?

Jakebe: Black history is American history. What my ancestors went through is the shadow side of the version of America we see in our history books and civics classes. A lot of us are shocked about what we’re seeing rising out of our fellow Americans in the current political landscape, but if we pay attention to the history of black Americans and the experiences of other Americans of color, we’d know that these attitudes have been around as long as the Constitution. This IS who we are; we’re just being forced to reckon with it.

At the same time, Black history helps me realize that resilience, perseverance, joy, and a commitment to working for my ideals are all a part of my story. My ancestors passed down amazing values and lessons to me, and it’s a privilege to get to be able to carry those stories and spread them as well as I can.

FWG: Do you feel that your Blackness has affected your writing?

Jakaebe: Absolutely. As a black man in America, you have to make peace with the fact that almost nothing you see is going to be from your perspective. The heroes we grow up watching and wanting to be like don’t necessarily look like us. I grew up queer and nerdy in the inner-city, so I’ve had a really difficult relationship with my Blackness because I’ve never felt accepted by my community. That feeling of being rejected by the dominant culture and my birth culture, of feeling alone and forced to make your own way, it’s always going to be a part of my work. I’m always reacting to that weird tension, of needing to belong but also realizing I never really have, and it shows in my writing. I’m still looking for my tribe.

FWG: Do you feel like the issues that affect the outside world affect your writing within the fandom or not?

Jakebe: They absolutely do. Since I’ve become more politically active I consider it a pretty core part of my job as a writer to find ways to express my perspective to a fandom audience that is largely white. It’s tough, when everyone in the community feels like they’re the underdogs in some way, to have a discussion about privilege or the blind spots they create. Furry literature can be a great way of exploring these sensitive topics in ways that folks are more likely to engage with.

FWG: Do you have favorite Black authors and has their literature affected your writing in the fandom?

Jakebe: YES. Ta-Nehesi Coates is my jam right now; he’s a fellow Baltimore native, and his personal essays have been a North Star for me in so many ways. He’s been killing it on Black Panther, too.

Octavia Butler has been writing amazing sci-fi and fantasy from a racial lens, and I hope to be able to achieve her level of insight and sensitivity some day. Kindred is such an amazing book. It really shakes your image of American slavery, what it would be like to endure that, and what you would do to combat the forces that shaped it.

There’s three-time Hugo Award winner N.K. Jemisin; there’s Nnedi Okorafor, who also won the Hugo Award for her novella Binti; there’s Daniel Jose Older, who is killing it with urban fantasy through an Afro-Latino lens; there’s Samuel “Chip” Delaney, the great old sci-fi Grandmaster who paved the way for all of us in the game right now.

It’s a really great time for Afrofuturist writers, and there are so many exciting stories being told that really break out of the traditional sci-fi and fantasy tropes.

FWG: If you could convince everyone to read a single book, what would it be?

Jakebe: I feel weird hyping this book after talking about so many excellent black writers, but if you haven’t read The Last Unicorn by Peter Beagle it is really a singular work. It’s both an homage to really great epic fantasy and a deconstruction of it; at the end of the novel, even though everyone has achieved what they set out to do each character is fundamentally changed in a way that makes them — and the world — so much more complicated. It’s a staggering, heartbreaking novel, and I love it so much. Most people only know the movie, but the book is better by an order of magnitude and Beagle deserves so much more recognition than he’s gotten.

FWG: Any last words for our readers and guild members?

Jakebe: In order to be an excellent writer, we have to spend so much more time listening and observing others. Listening and absorbing other people without judgement is an overlooked skill, and I think the time is ripe for writers who can present an honest understanding of others without dehumanizing or dismissing them. In so many ways, our separation between each other is an illusion. Our reality is connection.

—

You can find Jakebe’s writing on his blog From The Writing Desk and on his Patreon for serialized erotic fiction. You can also find him on Twitter both at @jakebe and @serialjackalope; as well as on Mastodon @jakebe@awoo.space. We hope you found this interview exciting and informative. We hope to continue these features next February for Black History Month as well as find other ways to feature black authors in the guild. If you have suggestions for how this might be done, please contact our public relations officer here. Until next time, may your words flow like water.

Furries For Bernie talk about their support for the US presidential candidate.

Join Bernie Sander’s Furs on Telegram.

Thank you for joining our movement! We'll never forget this moment. pic.twitter.com/vrSo3ANAUM

— People for Bernie (@People4Bernie) March 1, 2020

This is OUR moment, and if we keep building our movement, this moment will go on until we win and build the world we demand!  #NotMeUs pic.twitter.com/mMqoL6vpNU

#NotMeUs pic.twitter.com/mMqoL6vpNU

— People for Bernie (@People4Bernie) March 1, 2020

How we got covered by KQED in A Secret Weapon of the Progressive Left: Furries by Nastia Voynovskaya.

There was no time for breakfast. It would take a miracle to find parking for the Bernie Sanders rally in Richmond CA. We were nearby and already together after a dance party the night before. Now we could see him speak with 11,000 supporters.

Candy, BerryPecanTart and Lux rode with me. Wild Child and Zahi were there, and Apollo Wolfdog, who we didn’t know, made contact from seeing us in the crowd. We were a litter worth of furries in the blocks long line to get in while Bernie’s motorcade passed 10 feet away. The blazing sun and fursuit photos weren’t as big as a wave from the man himself.

His speech praised supporters in attendance like Danny Glover, and Richmond city government officers. Their movement featured in the 2017 book Refinery Town: Big Oil, Big Money, and the Remaking of an American City (Sanders wrote the introduction.) The book followed the path of history that passed beneath our paws.

The rally was in a former Ford factory that helped win WWII while union workers struggled with segregation. The town’s industry then became dominated by Chevron, whose refinery sometimes has fires like one in 2012 that hospitalized 10,000. Sometimes I can watch these industrial accidents with binoculars.

Climate change in action — I saw this scrapyard fire a few blocks from the rally site in 2017.

Chevron’s millions bought the city government for a long time, gaining power over development or costs like liability for people getting sick from pollution. That changed in the 2000’s. Despite being vastly outspent, progressives took power. It was what Sanders hopes to accomplish with his 2020 campaign.

At the rally, the fire was in Bernie’s challenge for a leader who listens to scientists, not climate change deniers, and a message of #NotMeUs. Even a furry could feel a stake in it (such as their high LGBTQ membership.)

Later some online watchers worried that being there in fursuit could make Bernie look bad. But in the crowd, there was nothing but positivity. Kids just old enough to start voting got energized. A candidate for US Congress asked for help with his race. They wouldn’t stop asking for photos.

KQED took one. When I shared it, they noticed all the animal-people sharing it too. That led to meeting the reporter and giving tips on good furries to talk to. This Twitter thread covers how.

This furry news story from 2017 had an optimist point about bringing attention to causes. https://t.co/o8BLdua4bF

I was reminded of it when @ShahidForChange asked me for photos at Bernie's rally today. He said 1 volunteer like this is worth 50 in a crowd. #furries4bernie 1/ pic.twitter.com/DE1bLSQyR3

— Dogpatch Press (@DogpatchPress) February 18, 2020

I can't speak about fursuiting at rallies, but I've had a fair bit of experience fursuiting at events like make-a-wish or relay for Life, and the positive effect on those people of us being out there and suiting is very obvious. Definitely not the stigma we expect!

— Inkblitz  Furnal Equinox! (@Inkblitzer) February 18, 2020

Furnal Equinox! (@Inkblitzer) February 18, 2020

Why Furries For Bernie? Quotes from those at the Richmond rally.

Lux Operon:

Bernie Sanders is a populist candidate, undeniably. He’s an underdog, a long shot. It wasn’t too long ago that he was hosting rallies in barns and backyards with 20 people in attendance. He’s struggled his entire life to be taken seriously. He’s almost like an imaginary character himself? How can we, furries, not identify at least a little bit with that? We all had a life before we came to the fandom, and for many of us it was a less than happy one. We all struggled to be understood and to be treated with respect. When we found our community and found an outlet of self-expression, we could discover who we truly were. The fandom is our pulpit, just like the presidential race is Bernie’s. He’s polarizing? He’s spirited? In another life, he’d be a furry.

If you’re asking me what his fursona would be, I would imagine it’s a secretary bird. Not only does it have the correct hair, but I can imagine Bernie kicking a snake in the head.

BerryPecanTart:

Well, as you know, back in 2017 at Anime Boston, Bernie’s benevolent presence was enough on its own to stop a fight of ultimate destiny between Strobes the Lynx and Jack Skellington. I can only imagine what peaceful reactions he can bring between the U.S. and the Middle East if he became president?

But in all seriousness, Bernie’s message of unity and togetherness in the face of overwhelming odds, from years of ridicule from constantly being on the right side of history, is something that us furries have understood too well. It’s a window of opportunity that has never been bigger in the history of the United States for an openly Democratic Socialist candidate to make it to the White House in over a hundred years.

And as a community that has opened its arms wide to the LGBTQ community and the first to push back hard against the alt-right (whether they been the Burned Furs or Furry Raiders), we understand the stakes better than anyone.

Wild Child:

Bernie means justice in desperate times!

Bernie means removing the crushing boot which the Establishment (Left and Right) and War Industrial Complex (see President Eisenhower’s speech on it) have held against the peoples’ throat for decades. This frees the people to be healthy, happy and live with dignity; Even when diginity is being a talking lion, frolicking with your friends. Speaking of, Bernie is a wonderful specimen of Lion, look at his poofy mane and magnanimous leadership!

Bernie means standing for the right thing, even when it is not popular. Bernie is honorable. Though to be honest, he needs to take off the gloves and confront war criminals like Biden.

The Facebook group Furries for Bernie:

Originally I made this page as a joke between me and my furry friends: wouldnt be funny if Bernie himself had a fursona and was an active member of our fandom? I made a few images that went with the page and slowly I realized people liked the idea! Bernie supports a lot of the ideals the fandom holds: LGBTQ+ rights, educational rights and animal rights. More than just being a supporter of Bernie personally I think the fandom of furries could get behind him for what he stands for.

"A Secret Weapon of the Progressive Left: Furries"

You heard it here first.https://t.co/UvqcPaOTb6

—  Shahid Buttar for Congress (@ShahidForChange) February 28, 2020

Shahid Buttar for Congress (@ShahidForChange) February 28, 2020

Watch out for trolls…

When KQED (a PBS/NPR type channel) did a Furries For Bernie tweet, it drew tagging from small trolls who tried to sic big trolls on it. One they tagged is known as a Republican political consultant and deliberate spreader of fake news with 180,000 followers. Recently a Fox “news” story shared it with no news content; it was a naked boost for a twitter troll by major media. It showed how the playing field tilts.

More chat about getting involved.

Arrkay: I think the Worst Year Ever podcast helped a lot for furries on the left. My brother is campaigning for Bernie on college campuses here in Canada. He was super awkward about furry stuff for years because of Somethingawful prejudices. After the podcast we had some great conversations. He tells me that the Americans abroad caucus is larger than any individual state caucus.

Patch: Why Canada, is it a lot of students and military?

Arrkay: I think students are the easiest to target.

Goku!: The next time Bernie comes to PA, I should really dress up in my rat suit- we could show rodent solidarity for him! Time to get in Brooklyn and have a hell of a time. I’d be perfectly fine just chilling outside and socializing with local citizens… but I wonder if they’d let me inside in fursuit?

Patch: No problem here, they just made me take off my head for a sec, they weren’t checking ID or anything either. Do it and use the hashtag if you do make it to the rally. Make a hashtag sign too, I must have gotten over 100 photos and would have seen more if I remembered to do that. They wouldn’t let home made signs inside but the crowds outside made it worthwhile.

Wild Child: One more reason to support… Bernie makes cruelty against animals a topic discussion more than most politicians, and he has a thriving Facebook page for it and platform policies on humane treatment.

Like the article? These take hard work. For more free furry news, please follow on Twitter or support not-for-profit Dogpatch Press on Patreon. Want to get involved? Share news on these subreddits: r/furrydiscuss for anything — or r/waginheaven for the best of the community. Or send guest writing here.

2019 Cóyotl Awards Voting Open!

We here at the Furry Writers’ Guild are proud to announce that voting for the 2019 Cóyotl Awards is now open! Let’s take a look at the great works of literature up for the vote.

Best Short Story:

“Dirty Rats” by Jan Seigal (The Jackal Who Came In From The Cold)

“Night’s Dawn” by Jaden Drakus (FANG 10)

“Pack” by Sparf (Patterns in Frost: Stories from New Tibet)

Best Novella:

“Minor Mage” by T. Kingfisher

“Love Me To Death” by Frances Pauli

Best Novel:

“Titles” by Kyell Gold

“Symphony of Shifting Tides” by Leilani Wilson

“Fair Trade” by Gre7g Luterman

“Nexus Nine” by Mary E. Lowd

“The Student – Volume Three” by Joe H. Sherman

Best Anthology:

“Patterns in Frost: Stories from New Tibet” edited by Tim Susman

“Fang 9” edited by Ashe Valisca

“Fang 10” Edited by Kyell Gold & Sparf

2019 Cóyotl Awards Voting Form

We hope to see many members of the guild come together to vote for their favorite works from 2019. Voting will remain open from March 1st through March 31st so make sure to get in that vote!

Issue 6

Welcome to Issue 6 of Zooscape!

As winter melts into spring, readers and bears alike awake from their hibernation.

Emerge from your cave, dear reader-bear, look around, and see the new stories we have for you to read!

* * *

Dragon Child by Stella B. James

Double Helix by Lucia Iglesias

The Bone Poet and God by Matt Dovey

The Hedgehog and the Pine Cone by Gwynne Garfinkle

As If Waiting by A. Katherine Black

The Adventures of WaterBear and Moss Piglet by Sandy Parsons

* * *

Once you’ve seen these stories—full of dragons and bears; creatures gigantic and minuscule; voyages both out into the universe and inward to the truest self—feel free to withdraw into your cave and read them in deep, dark seclusion. But don’t hoard them like a dragon, keeping the stories hidden forever in your cave.

After poring over this treasure trove of words, savoring them, and delighting in them, don’t keep them only for yourself—share the treasure! Share our stories far and wide. As always, if you want to support Zooscape more directly, we have a Patreon.

Exciting news!

Zooscape has been nominated for an Ursa Major Award! Thank you very much to everyone who helped nominate us, and if you enjoy Zooscape, please consider voting for us. Voting is easy to do and open to everyone!

Have a beautiful spring, and we’ll see you this summer!

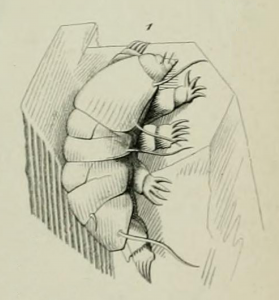

The Adventures of WaterBear and Moss Piglet

by Sandy Parsons

“He floated with eight claws extended, sailing his body like a kite, riding the waves between particles.”

“He floated with eight claws extended, sailing his body like a kite, riding the waves between particles.”

Deep in the 100 mm petri dish, WaterBear and Moss Piglet played. Light signaled the arrival of Crystal Robin. She had so many fun toys. “What do you think she’ll do to us today?” asked Piglet. He was a very timid tardigrade.

“Maybe she’ll put us on the Merry-go-Round. We’ll get dizzy.”

“No, I don’t think I’d like that.” The last time Crystal had centrifuged them he’d been a tun for weeks. “I’m still trying to get back to my full size.”

“I like you the way you are.”

Piglet said, “I hope we are always friends.”

WaterBear said, “We are tardigrades, we will always be something. But being friends is best.”

Crystal was looking at the x-rays from yesterday. “I can see inside your tummy,” said Piglet, giggling.

“Is it very Rumbly?” asked WaterBear.

“It’s full of agar,” said Piglet.

“Oh bother, that must be left over from the last time she smeared us on a slide. I very much wish it were something sweet. Do you happen to have any trehalose in you, perhaps?” WaterBear leaned over and wiggled the hairy ridges which covered his snout.

Piglet hopped sideways. “I’ll need it if she freezes us again.”

Crystal talked to them while she fed them their lichens and moss and freshened their water. Her favorite stories were about Outer Space. “I bet you guys will be the best astronauts ever. There’s nothing you can’t survive, so far anyway.” Crystal created more games, fire and ice and pressure so nice. She always told the tardigrades what she was doing but the words were long and often muffled by the sound of lichens being chomped. Once, Crystal aerosolized them. WaterBear and Piglet, floating in the ether, waving eight stubby legs at each other. “Look I’m a Roll-y-Poley,” said Piglet, rolling into a perfect ball.

WaterBear tried it too, but he was a tubby tardigrade and no matter how much he clenched his paws and scrunched his snout to his bottom he couldn’t transform from long into round. He floated with eight claws extended, sailing his body like a kite, riding the waves between particles. When the experiment ended, and he was back in the 100mm petri dish, he felt positively withered, and didn’t shuffle or wiggle when Crystal shared the results. “You did so well, my little menagerie. I wish I could boop your cute snoots.”

“Did you hear that? She thinks we’re cute,” said Piglet.

“I don’t feel cute. I don’t even feel like me today.”

Piglet twiddled his front claws. “Do you want some of my trehalose?”

“No thank you. You’ll need it for the Big spearmint.”

“Wh-what are you talking about?”

“To the stars.” WaterBear pointed a claw upwards.

“I don’t want to, WaterBear. Here have my trehalose. I’ll stay here where its snuggly and moss and lichens are always close to my mouth.”

“Well, I won’t eat it all, but maybe just a taste?” When he finished, WaterBear hopped and scooted and wiggled until he was puffed out like a tardigrade again. Piglet had gone over to the edge, where the medium thickened, watching Crystal Robin’s assistants pack up the laboratory. WaterBear put a paw on Piglet’s back, to modulate the shock of the news to his moss piglet buddy. “All of us are going to Outer Space.”

“Even Crystal? But how will we get the lichens?” WaterBear tried to answer but Piglet scurried, creating trails through the media. “Maybe we can spell out a message? ‘S-o-m-e-t-a-r-d-i-g-r-a-d-e-s!'”

“She already knows we are here.” WaterBear put the three paws to his head. “Think of something else. Think. Think.”

“How about ‘O-u-t-e-r-S-p-a-c-e…N-O-m-o-s-s?’”

But it was too late. Hands clamped a cover on the plate and they jostled and gently sloshed as they settled into a new dark world. Crystal had packed them in foam and the last thing they heard was someone saying, “Rocket Park.”

“I will hold your paw, and whatever comes we will be brave together,” said WaterBear.

Once the 100mm dish was secured to a conduit on the Flange of the rocket, Crystal opened the lid and snuck a few snacks For the Ride. WaterBear tried to pay attention but he was sleepy from the nanoparticles Crystal’s team had spent all week injecting into the tardigrades to track them. They waited a long time for liftoff, Piglet twiddling his claws in between bites of moss and WaterBear taking one last traipse through the 100mm petri dish. Finally, the vibrations signaled the time to leave their Earthly home had come. “Stay by me,” said WaterBear, and they intertwined four sets of claws as the darkness and cold replaced warmth and light. The Flange shook and the conduit opened, and WaterBear and Piglet, media, food and all the other tardigrades floated into the Abyss.

Like reverse popcorn, the tardigrades turned into tuns, but WaterBear, who was even rounder in the middle now, couldn’t make his front claws meet the back ones. “Think, think,” he said, and Piglet, whose voice was muffled by his body, said “What’s wrong, WaterBear?”

“I think I’ve lost my tail.”

“Tardigrades don’t have tails, not even you.”

“Oh, well then, that’s a relief.” He was drying out fast, but still couldn’t form a ball. Then some space lichen smacked into him and his body reacted as it should. He was a tun, and Piglet floated next to him.

“Where are we going?” asked Piglet.

“I don’t know but at least we’ll be together.”

“Forever?”

“Even longer,” said WaterBear.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

As If Waiting

by A. Katherine Black

“A comfortably mild light surrounded her, like that of the Four Moons. Had night arrived? Was she outside? She cracked her eyelids.”

“A comfortably mild light surrounded her, like that of the Four Moons. Had night arrived? Was she outside? She cracked her eyelids.”

The fur on Aainah’s legs shifted as Jwartan’s tail wrapped around her ankles, seeking to comfort, or maybe to be comforted. She reached for his hand, unable to pull her gaze from the enormous serpent stretched across the valley below, at the creature that could not be and yet was, and she realized she should be filled with dread. But it was something else entirely that pressed against her ribs and somersaulted under her skin. It was exhilaration.

Large as half the village, the serpent oracle was still as stone, impossibly dark. Dark as all the tales told, rejecting the light of all four moons in the sky, as if this was something one could easily do.

It wasn’t until she and Jwartan broke through the treeline at the crest of the hill and gazed upon the serpent oracle that Aainah realized she’d never believed it was real. She’d expected nothing but a gathering of boulders, maybe an odd line of fallen trees. Because it had to be nothing, didn’t it? Nothing but a tale exaggerated to impossibility, like so many other myths spun by the elders to keep young ones in line. How could such a thing be true?

Just as no Onaphi could live at the river’s bottom, gripping the fins of sharp-toothed beasts and riding the undercurrents to far away oceans, just as no Onaphi could stretch and weave their fur into wings and take to the sky to battle the fiercest of predator birds, surely no Onaphi could step into the body of an enormous serpent and emerge from its eye with a wisdom so rich it could cleanse the most wretched of souls. Who could really believe such a thing, especially, as her mother had said, when no one alive had even seen the serpent with their own eyes? Now facing the vast, motionless creature below, Aainah realized she’d expected, hoped, the journey alone would serve as her healing agent, would fix the wrongness that held fast and stubborn to the dark corners of her mind.

Aromas of unfamiliar territory floated up the hill. Odd grasses, dirt too metallic, unknown diurnal creatures hiding with hoards of wilting fruits. Scents wafted into her nostrils from the right and from the left, leaving a gaping hole in front of them. An odorless void hung in the direction of the serpent oracle, as if her nostrils suddenly clogged with the mucus of sickness whenever she gazed its way.

Craning her ears forward, Aainah heard not even a tiny rustle. Not the slightest sigh of movement ahead. The entire clearing appeared as immobile as its giant inhabitant, as if holding its breath. As if waiting, for her.

If they ran toward it, right then, they might reach the oracle before daylight hit. Before the birds began hunting. There might have been time enough.

Jwartan gripped her shoulders. Shaking her gaze away from the serpent oracle, he asked that she give them one more day together. A final day. One last moment of now, before whatever was to be came to be. Aainah nestled her face in the crook of his neck. It was her favorite place in the world. She breathed in the dust of their long journey that clung now to his pelt. Of course, she said. She wouldn’t have it any other way.

What she didn’t say, despite the silent urging she felt from him, and from the village now many nights’ journey away, even from the impatient rustle of the trees overhead, she didn’t say she was sorry. Sorry for this exhausting journey, sorry for this budding excitement at witnessing the oracle before them. Sorry for being something other than what he wanted her to be. What everyone needed her to be.

Instead she slipped her arms around him and synced her breaths with his heartbeat, holding him close as she looked over his shoulder and through the trees at the Third Moon glistening above. The Third was her favorite for the same reason it was disliked by everyone else. It was the only moon whose face could not be seen, whose face was turned out, away from their world. Toward the stars.

As a young one, Aainah would ask her mother the same question every day before their sleep. What did the Third Moon see? What was it watching? Each time her mother swept the question aside with a small but firm flick of her tail, telling Aainah the Third watched nothing at all, because it had no face. How do you know, Aainah would ask. Because there is nothing else to see, her mother always said. There is nothing outside the villages and the waters, the mountains and the forests. If the third moon indeed had a face, her mother always said, it would be watching them. Aainah had stopped asking such questions around the same time she decided that there was more to life than her mother knew. Or than her mother wanted to know.

Curled together under a meager leaf shelter at the top of the hill, Aainah and Jwartan’s throats rumbled in harmony as they moved in hungry rhythm, until sleep insisted on taking its turn. They woke at dusk, entangled, their dreams slipping away as the suns slipped from the sky. He whispered to her then, of the future they must have. Of the future they deserved.

She stroked his whiskers but held back the words dangling on her tongue. She didn’t tell him that he was her only moonlight, the only beautiful thing in an otherwise bleak existence. Didn’t try to explain the racing heart that screamed as she woke, screamed at the thought of doing the same work, night after night, of listening to the same stories and seeing the same faces, until every night crept agonizingly on toward a dull and hopeless forever. Her future in the village frightened Aainah to no end, more than the prospect of the oracle serpent devouring her alive, and she knew Jwartan would turn his ears against such a truth.

The final steps of their journey together took longer than expected. They arrived at the serpent’s tail just as the first sun peeked over the horizon, spreading an uncomfortable warmth across Aainah’s fur as her eyes darted toward the sky, sure there were as many predator birds in this valley as in any other.

Engulfed in the shadow of the serpent’s tail, a tail that stretched higher than three of Aainah, she cursed the stories again. They never mentioned how to wake this oracle. Tales of the few who made the journey spent most of their words explaining the restlessness gnawing in the Onaphi’s gut, detailing how they didn’t fit in, how they couldn’t fit in with their tribe. How they hid in their huts all night or paced the edges of the village relentlessly. Their tails constantly twitched, even during sleep, and no task offered sufficient reward, no company calmed their minds. These restless ones left the village long ago to journey to the serpent oracle, to beg for relief from the wrongness that infected their thoughts. Some emerged from the eye of the serpent and returned to the village, returned to life a satisfied, changed Onaphi. Others emerged only to abandon the village in favor of solitude in the forests. And there were those hopeless few who never emerged.

Gaining entry to the belly of this oracle might be a test, a trial. Aainah consciously suppressed the anxious tic in her tail, wondering if Jwartan was watching. She didn’t turn to look. Instead she kept her ears craned on the puzzle of the oracle, refusing to add fuel to Jwartan’s hope about her, about them.

The serpent’s lack of motion, its lack of breath, was unsettling. Like the river monsters who lie in wait, still and deep under the surface of a stream, anxious to swallow whatever poor creature wandered too close. Feeling too much like one of those poor creatures, but not knowing what else to do, Aainah reached out and scraped a claw across the serpent’s solid body. Her sharp touch made no sound, left no mark. Pressing a full hand to the serpent’s side, Aainah felt an absence of cold, and an absence of warmth. It was like touching emptiness in solid form.

Sharp pain pierced a finger. Hissing, she jumped back, but could find no blemish on her hand, no spot tender to the touch. Still, something had bitten. Or stung.

She turned to Jwartan, to say something, although she didn’t know what. The serpent’s shadow extended even over him, standing several lengths away, protecting him from the harsh daytime suns. He, at least, deserved relief from the heat. He’d done nothing wrong, only volunteered to accompany Aainah on this journey.

So many years of courtship, so many nights on this exhaustive journey, and yet there he stood, at the end of it all, his back turned on her, just as the rest of their village had done. Just as her own mother had done, when Aainah finally stepped across the threshold into unclaimed territory, bound for the serpent oracle. Jwartan’s hands were on his hips, tail decisively raised. Fur rested on his spine in resignation, his posture said as much as his silence. Said all she needed to know. Come back different, it said, or don’t come back.

Aainah wholeheartedly agreed.

A chirping sound pulled her attention back to the serpent. Three lines of light appeared on its skin, at the level of Aainah’s chest. Like sticks laid in rows, the lines gradually merged together in the direction away from Jwartan.

An invitation.

One last look at Jwartan. Would she see him again? She soaked the sight of him in, his soft grey fur, the lovely bold stripes that zigged across his back. He may have turned on her, as was the custom, but now his ears were slightly, unmistakably tilted in her direction. His plea from their last dusk together, whispered fiercely as they’d curled in shelter against the setting suns, circled in her mind. He’d tell everyone she’d made it through the serpent, if she’d only turn back then. He’d promised. They’d never know.

But she would. And the question would remain. That unnamed question, rooted deep in her gut, consuming her joy before she could even taste it. Sucking the color from her future until it was all but a dry field, bleached in the merciless light of the high suns.

Standing at the tail of the serpent, Aainah was now destined for one thing or the other. To emerge from its Eye a free Onaphi, released from the grip of this restless curse, or to be consumed by the oracle beast. She spoke inwardly to the Third Moon. As the Third endured eternal scorn by the rest of the village, Aainah had always offered it her love, secretly. Quietly. She admired the Third, that it continued to rise night after night, to hold strong its place among its kind, despite the ridicule from her village and likely many others. And now she cast her inner voice out toward the place where the moons hid from the suns. This time, for the first time, she sent a request. She asked for a share of its strength. And its courage.

There was nothing left to do now, but go.

Touching the center line of light on the serpent oracle’s side, Aainah found a surprising absence of heat. The pads of her feet crunched dry gravel as she walked in the direction of the converging lines. Nearing the turn of the tail and the unshaded side of the beast, she prepared to bake under the suns, and to keep one eye on the sky. She wondered if the serpent would have her walk the full length of its body sunside, wondered if those who’d never returned hadn’t died in the serpent, but had simply been plucked from its side by some lucky predator bird who happened to be scouting the area.

At the very tip of the serpent’s enormous tail, only steps from the edge of its shadow, a doorway appeared, suddenly, noiselessly, revealing a darkness deeper even than the serpent’s outer skin. Deeper than anything Aainah had ever seen. She stepped inside.

The floor of the serpent’s belly was slick, yet dry. Nothing was visible beyond the light cast by the doorway, and that light closed in on itself, shrinking quickly to nothing before Aainah could react. She stood for many breaths, blind, considering her options. She might speak a greeting, or she might simply walk forward. With no other ideas springing to mind, she took a step, followed by another.

Her feet made no sound against the belly of the serpent. Neither did her breath. She stopped to breathe deeply, wrapping her arms around herself. In the soundless void, the rise and fall of her chest offered little comfort. She tried to speak. Pressing a hand to her throat, she felt the vibrations of her neck, as her mouth formed words that amounted to nothing. Had the serpent already decided to consume her, beginning with her voice? Her blood pulsed under her coat, running faster and faster around her insides, as if looking for an escape.

A harsh medicinal scent flooded her nostrils, similar to the crushed herbs the village healer smoothed over cuts, but stronger by multitudes. She doubled over in a fit of silent coughing.

Sharp stabs hit her feet, releasing a chorus of pain. She jumped reflexively, and landed at an odd angle, twisting one leg. She curled into a ball, wrapping her tail around quivering limbs. An urge gripped her mind. To run, to search for the doorway and pound on it, to scream for Jwartan.

But then what?

Would he forgive her foolishness, for undertaking a pointless journey? Would he expect her to be different? Could she pretend to be different?

Fierce itching began at her torso and spread quickly, wrapping around her body until every speck of skin under her fur burned. Attempts to scratch caused the burn to build, until it became something barely tolerable. Was this how the serpent ingested the unworthy?

A wind of cold hit just then, providing a slight relief from the itching. But this wasn’t just cold. This was a freeze. Pressing in from all sides, threatening to steal her breath. As if she stood at the highest snow-capped mountain top, all her fur cruelly plucked away. A fleeting wish flashed through her as her mind grew dim. If only she was instead on a mountain top, bird nests be damned, at least she could gaze upon the Third Moon once more, before her body slipped away.

Her thoughts narrowed, iced over along with her body, slipped from her grasp until there was nothing left but quiet. Nothing but darkness. Deep chill coated in heavy silence. Tipping sideways, she curled as tightly as she could, attempting to trap the last of her body’s warmth as cold enveloped her. If this was the end, it had come so soon.

Feeling fell away. Thoughts cracked.

Jwartan’s face floated in the near void of her mind, his eyes relaxed, whiskers slanted in the expression he sent her so often, secretly, from across a crowded room, in the way he let her know he was thinking of her. His fur fell away, then, as did his eyes and whiskers, leaving nothing but a gaping emptiness in his grey face, unreadable. Like the Third Moon. She spoke to the moon, then, and also to Jwartan. If this was the end, it had come too soon.

Dim light seeped through Aainah’s eyelids, although they remained closed. She lay on her side, curled tightly, wondering how many breaths had passed. The cold was gone. Ideas, memories, feelings, all poured back in. A comfortably mild light surrounded her, like that of the Four Moons. Had night arrived? Was she outside? She cracked her eyelids.

She was inside a room, windowless, yet somehow lit by unseen moons, or unseen fire. Floor, walls, and ceiling each curved, one blending into the another, all with the same colorless hue of the serpent’s outer skin.

Standing on shaky legs, Aainah noticed the floor give slightly to her step, like soil would. Yet this floor was not a gathering of countless grains, but one complete piece. Circling, Aainah turned her ears in all directions, listening for any sound as she scanned the surroundings. The serpent might have given her light, but sound was still absent.

Why had none of the stories told of what lay within the belly of the serpent? The answer laughed within her. What if they had? What story could she tell, so far? Color absent of color, darker than dark, colder than cold, a noiseless room lighted by absent moons or unseen fire? Her head lightened with the absurdity of it.

Aainah slowed her pacing to stand, waiting to see what the serpent would do next. As if responding, a doorway opened. She stepped through. It led to another room, about the same width, but longer. A light wind kissed the fur on her tail, and the doorway behind her was gone.

Sound flooded in. She could hear herself breathe again. She chuckled. Her voice sounded strange, different than she remembered it. She jumped at the appearance of a shape, on the wall next to her.

It was the size of a grown Onaphi, of Aainah. Through it, she could see the grounds outside the serpent. It was night. The Fourth Moon was visible, grinning large and friendly in the sky as it surveyed the scene. She stepped closer to the opening, just close enough to glimpse the Third Moon. It was small and blank, as usual, its face looking other places. Reminding Aainah that there were other things to see.

Scanning the grounds through the opening, Jwartan was nowhere to be seen. So that was it. He had already left. How many days and nights had passed while she lay frozen inside the serpent?

Aainah reached a hand out and passed it through the opening. The air outside was coarse, draped in dew. This doorway was real. She could leave. She couldn’t possibly have reached the eye already, yet the serpent was granting her an exit. Why? Was she cured? No, she was sure she wasn’t. She felt like the same Aainah.

It was her mother who’d first recognized Aainah’s need for the serpent’s healing. Aainah may have hid her sorrow and restlessness from the rest of the village, even from Jwartan, but her mother was in the habit of looking deeper than others felt comfortable. The moment she’d shared her idea with Aainah, that she travel to the oracle and address her pain, the words could not be undone, took on a weight and strength only truth could sustain. Aainah stepped beyond the village’s boundary three nights later.

Before turning her back on her daughter, Aainah’s mother had whispered her farewell, the red stripes under her chin barely moving as she spoke in the same hushed tone she’d used to tell stories to Aainah long after dawn had broken, while her siblings curled together in contented slumber. As the rest of the Onaphi lined the edge of the village, their backs already turned on Aainah, her mother looked her in the eyes one last time and told her that she would make it through the serpent. All the way to the Eye. And whatever happened then, Aainah would become her true self. Aainah asked her mother, in a voice too small for her body, “but how do you know?” Her mother’s only response was a purr, soft and steady—a sound Aainah hadn’t heard from her mother in many seasons—as she turned her back on Aainah.

A line of dryness crept across Aainah’s arm as she pulled her hand back into the belly of the serpent. She was not done here. The doorway collapsed at the very moment Aainah’s hand returned. Shadow appeared in the corner of Aainah’s vision. An opening, to another section of the serpent. A familiar tic pulled at Aainah’s tail, but she had no interest in suppressing it this time. The jittery feeling it betrayed wasn’t annoyance, and definitely wasn’t the boredom of village life. It was anticipation. A few quick steps, and she ducked into another room within the belly of the serpent.

As if someone had reached into the sky and covered all moons but the Third, this room was dimmer. The doorway closed behind her.

Like the others, this room was also empty. Or so it seemed, at first. A noise behind her made Aainah jump nearly a full Onaphi length and hit her head against the top of the serpent’s body, bending her neck painfully before she fell to the floor. She stilled, slowed her breathing, and listened. Rustling. Just behind her.

On all fours, tail stiff and ears craned, Aainah turned, and came face-to-face with a child. Small, with a soft pale coat, it crouched against the wall, tail wrapped around its hands and feet. It shivered, although the room did not feel cold to Aainah. She breathed in deeply and found an absence of smell, not only of the child, but also of herself. No whiff of earth caked to her feet, no lingering aroma from the last meal she’d shared with Jwartan.

A black spot decorated the fur around one of the child’s eyes, eyes that seemed too serious to belong to a child. All in the Onaphi village bore stripes on their coats. All but one. The only Onaphi Aainah knew with spotted fur was a strange elder, the Counter, who slept outside the door to the village store room, right in the middle of the blazing sunlight, and spent every night with its back bent, counting and re-counting the village’s supplies.

Fidgeting and prowling the back rows during village gatherings, as young Onaphi do, the youths would whisper, speculate, suspect the Counter had been birthed in another village, far from their own. This idea remained more story than truth, as adults refused to discuss the matter, and the young were afraid to approach the spotted elder, who only spoke in numbers.

Come to think of it, Aainah was sure the old Onaphi had a black spot over one eye, just like this child.

Aainah relaxed her posture and offered from her throat a soft, pacifying rumble, as she approached the child. It was indeed young. The child hadn’t yet grown fangs. How had it survived in the belly of the serpent? Aainah wondered if its language was similar to her own.

“Do you speak, young one?”

In the blink of an eye, the child’s shivering ceased. Its tail loosened from its body and raised a few finger-lengths off the floor. Its ears craned toward her. She spoke again, lessening the rumble in her voice, to provide clarity.

“Need help, young one?”

The child visibly relaxed and emitted a mild rumble from its own throat. It was starting to trust her. She took another step forward, but the child slid away in equal measure. Now wanting not to endanger the fragile bond only just formed, Aainah remained where she was and leaned back on her haunches, to match the child’s posture.

Stories of Onaphi journeying to the oracle were so few, so old, she hadn’t even considered she might find another person within the belly of the serpent, but she supposed it made sense. Other villages must also lay within journeying distance of the serpent oracle. But a child? What sort of village would turn its back on a child? What sort of child would be sent away? It must have been lost. Must have stumbled upon the serpent and hoped for shelter inside, safety from flying predators and baking suns.

The child’s tail raised until the tip was visible over its head, as if being startled by a stranger within the body of an enormous serpent was already entirely forgotten, or was something that happened every night.

“Who you are?” Its voice was odd, words confused as a child might do, yet spoken with a clarity that reminded Aainah of a story-teller, of the Onaphi tellers, who stored the lives of all villagers past and present neatly within their minds and let pieces of those lives tumble from their mouths in clear patient tones, to be snapped up by rapt ears and reborn in slumbering dreams.

“Am I?” Aainah’s throat rumbled in an attempt, she was aware, to reassure herself as much as this child who was not at all childlike. “I am Aainah.”

“Are you, are Aainah, friend?” Its eyes, intent, almost wise, transfixed Aainah. Made the small thing look less and less Onaphi.

Studying the unexpected little one before her, Aainah realized she’d only seen people from other villages a sparse few times in her entire life. She felt her tail raise still and high above her head, as enough questions to fill three store rooms quickly piled up within, waiting at the back of her throat. Controlling her curiosity with some effort, she said, “I am glad to be your friend. If you want.”

Purring as it stood, the child walked the few steps between them and bent to nearly meet with Aainah’s nose where she sat. Its lack of scent was distracting.

“Aainah friend, come with?”

The child giggled as it evaporated into mist.

Tensing, Aainah turned in tight circles, scanning the room. The child was gone, as was the mist. Her head felt heavy and light at once. Her vision lurched. She stumbled, tripped over nothing but her own confusion, wondered if the child had been snatched by something as unseen as the moons in this place, or if the child had been nothing but a creation of her own mind, a mind that must now be far beyond help’s reach.

A breeze tickled the backs of her ears, carrying with it scents. Welcome, familiar aromas. Grounding smells. Of gravel, of weeds and trees. Of Onaphi, one Onaphi in particular. She turned with caution, unsure whether she wanted to lay eyes on the things she sniffed.

He sat in the doorway, posture tentative, wide eyes fixed on her.

“How did you get in here?” She approached the doorway and sat, opposite him.

“I’ve been waiting outside. It’s been two nights.” His whiskers trembled. “You look awful.”

She surveyed herself, saw what Jwartan saw. Clumps of fur were missing, all over her body, the skin underneath scabbed and abnormally colored. Thoughts slipped from her grasp, scrambled too fast around her mind to be caught. She searched his face. He answered a question she didn’t ask.

“A doorway opened. I thought I was imagining it. But then I walked in.”

Despite the scents, despite the voice, she wondered if he was real. Unsure what to do, she began counting her breaths, silently, expecting him to disappear into mist after each exhale.

“Is this part, am I part of the serpent’s test?”

“Maybe. Yes.”

“What has it done to you?” Tears spilled from his eyes.

She reached through the doorway, smoothed the wet fur on his face.

“It’s over, isn’t it?” His throat rumbled. “Come home with me.” He leaned through the doorway and rubbed his cheek against hers, reached for her and pulled her into his embrace. Nuzzling against his neck, she felt everything that was home. Warmth, stories under the light of the Four Moons, savory fish just pulled from the fire, children racing between rooms and wrestling in giggling piles, sparking laughter in even the most serious of elders. Jwartan would always be home to her, all that home could be.

“You’re better now. You’re fixed, aren’t you?”

He was as he always had been, warmth and tradition, just as Aainah realized she was still, she remained, all that she had been.

“It’s not finished.” She withdrew from his embrace. “I’m not ready.”

He stilled. “What’s happened in here?”

Words could not explain. “Not enough.”

His tail bushed, ears tilted away. “I can’t wait forever.”

She’d never seen the value in games like this. Especially now, after the freeze, after watching a child vanish before her eyes. “I understand.”

His shoulders sank. He looked to one side, maybe toward a doorway. His exit.

“Remember us.”

He stood and began walking, his tail dragging on the floor, as the doorway between them collapsed before her eyes. Tears clouded her vision. She’d been too harsh. He hadn’t deserved that. A new doorway opened a few steps away. She immediately walked through.

Nothing like the other rooms, this one was lined on either side with what looked like glistening trunks of trees with slick, silvery bark, like a river-buffed rock, nearly sparkling. Like ribs. She was nearing the serpent’s head. Nearing its eye.

She walked through the ribs of the serpent.

The shining bones apparently protected no organs, no blood, nothing that she could see. Nothing except her. As she walked, tall windows opened between the ribs. Aainah squinted at the bright midday light that poured into the serpent, almost reaching her feet. Though she could see plant life out there, soaking in the nectar of the suns, no breeze trickled through, no scent of trees or grass.

Sitting beneath a tree was Jwartan, holding out a wide bawn leaf in an attempt to shade his feet. She’d thought he’d be running back to the village, after what he’d said, to join everyone else, everyone who wanted to be there. Yet, despite his hard words, it appeared he was willing to wait, even to sit fully awake, surrounded on all sides by the blaze of high suns. For her.

Aainah watched him as she continued through the serpent’s ribs, as he shifted deeper under the tree’s cover, until his face was no longer visible. She walked until the sight of Jwartan was well behind her, until she’d nearly reached the other end of the serpent’s belly. Until movement outside snagged her attention and pulled her to the window before any thoughts could be formed. Two birds glided toward the tree, toward Jwartan’s meager shelter, until they circled above, their wingspans as wide as half the tree’s height, their beaks easily larger than an Onaphi head.

Only Jwartan’s feet were visible under the bawn leaf, and they didn’t move. Clearly he couldn’t hear the predators. Maybe he’d fallen asleep. Who wouldn’t in the height of day? She screamed his name. Her voice echoed through the belly of the serpent, but clearly didn’t escape the oracle. She pressed her hands against the invisible skin of the serpent, the skin that showed her love nearly snatched, nearly eaten. Hard as stone, it didn’t budge. She kicked and slammed and snarled as the birds glided down, down, until they were nearly above the top of the tree. They would land soon, on either side of Jwartan. He’d have no way out. He’d die, in the most horrible way, all because of her.

“Let me out!”

The unseen skin covering the window disappeared, and Aainah fell through, screaming his name. Jwartan dropped his leaf shade and stood as the birds hollered, their hunt interrupted. They circled tightly and dove toward Aainah, who lay half in and half out of the serpent’s window. It was Jwartan who screamed her name this time, told her to run, as he climbed the tree to dive under thicker leaf cover.

The air hissed as it parted, making way for the two birds diving her way. She scrambled backward, back into the serpent, only a body-length away from death when she made it inside and yelled at the serpent to close the window.

One bird reached her before the other. She heard nothing as its beak cracked and shattered against the serpent’s invisible skin, now apparently back in place. The second bird steeply turned upward as the first collapsed in front of Aainah, its skull misshapen as blood quickly spilled into the ground. She looked to the tree and saw nothing. Jwartan was safe.

Sinking to the floor and wrapping her tail around her shaking limbs, Aainah tried to still her panicked heart, soften the gasps escaping her mouth. It was over. All was okay.

But it might not have been. Look what Jwartan had risked, continued to risk. For the sake of someone who barely knew how to love him back.

All the windows within the serpent’s belly closed at once, forcing her vision to adjust to the milder lighting. A doorway opened at the end of the room. Only a few steps away. Darkness, deep silence, lay through the door, offering no hint of the next trial that awaited.

The promise of something more sparked anew within her breast, quieting her heart. She would continue. Jwartan’s risks would not be for nothing. She walked through the door.

Light raised to a perfect dim. Curiously curved tables scattered around the room and lined its curved walls. The tables were taller than those they built in the villages. They held puzzling shapes, like small tools, attached to their surfaces. Aainah wandered the room, considered whether she should try to touch or move some of the tools. She was examining a table along the far wall when the serpent spoke.

It was the perfection of the voice, ageless, foreign, similar to that of the child but too clear to come from an Onaphi throat, that led Aainah to realize who was speaking. Its words were hard and exact, like a stone smoothed to perfection in a way no Onaphi could never achieve, in a way only a mighty volcano might accomplish.

“You have done well. Your body is healthy and strong. This means you now have one more choice to make.”

Aainah leaped backward when the wall before her sprang to life. It was as if she could see into another serpent’s head, an exact copy of the strange room in which she now stood. As if a window had opened to show Aainah not the grounds outside the serpent oracle’s body, but another time within its body. It showed other Onaphi, one after another, standing within the serpent, nearly where Aainah herself stood. She looked around to confirm she was alone, yet she looked back to the window to see that no, she was not alone. Despite her head swimming at the experience, nothing could keep her eyes from the stories laid out before her.

A brown Onaphi with white stripes stood before a table. Its mouth and throat moved in words Aainah couldn’t hear, and then it walked through a doorway, into a room not much bigger than the Onaphi itself. The eye of the oracle. It leaned against the back wall, its ears in a resting position, as soft and peaceful as those of children in sleep, and the doorway closed. More Onaphi appeared on the screen, one after the other. Some walked into the small room, others left out another doorway, one that led outside. All of them, each Onaphi, when they left, held their tails high and turned their ears forward, intent on their choice. Which of those leaving the serpent had returned to their villages? What happened to those who elected to remain?

The choices of countless Onaphi played out before her. Each chose one of the serpent’s Eyes, either stepping into the small room or leaving the serpent’s body. Just as Aainah grew accustomed to seeing these scenes that were somehow happening and not happening in the very room where she stood alone, she froze. A face emerged that she recognized. She would know that face anywhere.

Aainah left her mother, an elder, back in the village only a handful of nights ago, yet the Onaphi in the scene before Aainah, with her red striped chin, was also undoubtedly her mother, but with a stronger posture, a fuller coat. Brighter eyes. It was she who’d told Aainah to seek the oracle, she who’d told story upon story of the few who’d made the journey and returned, yet Aainah’s mother had never mentioned that she’d walked through the serpent herself.

Aainah held her breath as she watched her mother, so young, speak silently to the serpent. So very familiar was her mother’s face, Aainah thought she could almost make out what she was saying. Almost, but not quite. Of course Aainah knew the choice her mother had made, so long ago. And yet…

Maybe it was because she knew her mother’s movements so well that she saw something in the young Onaphi she’d not noticed in the others who’d just chosen their fate before Aainah’s eyes. The younger version of her mother had made her choice, had walked through the eye that led outside, and while she held her tail high, Aainah noticed the slightest twitch at its tip. Just once.

Maybe it was from watching her mother so closely during all of her growing up years, to see if her mother would reward her for a job well done or punish her for one of many defiances, that Aainah understood so well the position of her mother’s ears. They faced forward, yes, but they weren’t as eager, weren’t as sure. Not craned fully forward with complete contentment and full acceptance. One ear held back. Tilted, ever so slightly, still trying to soak in the sounds of the serpent her mother had left.

Aainah’s mother had always seemed so sure, yet she’d felt regret, back then. Had others been regretful, also? Had those who stepped into the small room felt just as much regret as those who returned to the outside?

“The time is now, Aainah the Onaphi. It is your turn to choose.”

Two doorways opened.

“Return to your life, and be assured your visit is greatly appreciated. Choose the other doorway, and you will leave your home, never to return. You will travel to another place, far beyond the stars in your sky, where other creatures wait, happy to be your friend. Some there are Onaphi, most are not. Most will look different, speak different, think different.

“All will be glad to know you.”

Aainah’s tail fell to the floor. Another place. Not to return.

Jwartan was still outside, waiting. She stepped toward the doorway to see him standing against the tree again, leaning against the trunk. He faced another section of the serpent, his profile strong. His jaw set. The suns cut a sharp angle past the cover of the tree, spilling heat across his back, but he did not move. His devotion was clear. He would endure pain for her, would support her always. She could walk outside, tuck into his embrace, return with him to a shared future within the village. He would accept her, she now realized, exactly as she was. He would never question. But she would.

She was at the end of the serpent oracle’s journey, and she was still the same Aainah.

“It is your turn to choose.”

Her tail lifted as she soaked in the vision of her Jwartan, standing under meager cover, surrounded by the heat of the blazing suns, waiting for her. She said only two words, quietly. His ears perked, tilted in her direction, followed by his head. They faced each other across the barrier of the serpent, across a distance greater than the number of steps it would take to cross. She closed her eyes and dipped her forehead forward, imagining it meeting Jwartan’s.

She left the doorway that led to Jwartan and walked toward the other and through, then leaned against the back wall of the tiny room. The doorway closed in front of her, leaving all but a small section the size of her face, a window. Pressure enveloped her body, holding her still, yet allowing her to breathe. Her tail tried to twitch, but it was held fast, curled around her leg.

Watching through the window, she saw the small room, the eye of the oracle, somehow lifted up, pulled away from the serpent, raised until it was above the serpent’s body, as if the eye had grown wings. The tree that sheltered Jwartan was visible for only a second as the land quickly fell away. She couldn’t hear her own laughter as birds flew across her vision, apparently unaware of the wonder that was happening at that moment.

She considered, as the land drew away, maybe she’d simply lost her mind. Maybe she still laid frozen just inside the serpent’s tail. Another part of her, the part brimming with a joy that swiftly lighted her thoughts, decided it didn’t matter. This journey was worth more than four lives in an Onaphi village, real or imagined.

Mountaintops slipped past, as did the searing light of the suns. An enormous gray rock came into view. Though it loomed larger than she could have dreamed, she recognized it immediately. It was the First Moon. Her gut shifted as she curved around its rough backside before moving on to the Second, purple and oddly fogged over. And then the Third lay before her.

She glimpsed its side. Her tail would have twitched like mad if it could have. She was about to see its face. The thing no one saw. The thing her mother told her didn’t exist. But then her mother hadn’t told her everything. A few breaths passed, and then the face of the Third spread before her. Her heart swarmed, as broken, discordant parts inside of her coalesced, finally, into something that felt whole.

Dark, dimpled, she could see its nose. Its eyes. Facing out. Facing her. Behind the Third was a strange pocked thing, with patches of color and soft clouds drifting over. That must’ve been her home, where children darted in and out of rooms and birds prowled the sky, where her mother remained. Where Jwartan stood. Yet the Third didn’t care about such things. Facing away from the land, away from the mountains, away even from the serpent, the Third only watched the stars.

Aainah now felt pity for her beloved Third Moon, forever stuck in place among its family, unable to accompany her on this indescribable journey. With her inner voice, Aainah thanked the serpent for freeing her, for sending her to a place where she would not be considered wrong.

As the land of the Onaphi and the Third Moon both fell away beneath her feet, she spoke silently. I will go in your stead, but rest assured. A part of you travels with me. She relaxed into the serpent’s embrace, as countless stars passed before her eyes.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

A. Katherine Black is an audiologist and a writer. She adores multicolored pens, stories featuring giant spiders, and almost everything at 2am. She lives in a house surrounded by very tall and occasionally judgmental trees, along with her family, their cats, and her overused coffee machines. Find her on flywithpigs.com or on twitter at @akatherineblack.

The Hedgehog and the Pine Cone

by Gwynne Garfinkle

“There were no dog-eared pages, no underlines or annotations. Purple climbed inside and pulled the pages shut.”

“There were no dog-eared pages, no underlines or annotations. Purple climbed inside and pulled the pages shut.”

This is the story of Purple and Green, two hedgehogs who were the best of friends. They rolled and played on the forest floor. The hedgehogs were spiny and guarded, but they knew how to reach each other. They feasted on berries and mushrooms, bright frogs and luminous snails, while they told each other the funniest and saddest and strangest stories they could think of. Some were stories they’d read in books, while others were anecdotes they’d heard from other hedgehogs or happenings from their own lives. Even calamities that had befallen them became fodder for their stories, offered up for each other’s enjoyment.

Then one morning, Purple found that Green had turned into a pine cone, armored and inanimate. Purple butted her head against Green, but instead of giggling or waddling in a circle or poking Purple with her snout, she wobbled and grew still once more. “Green, please speak to me,” Purple implored. “How did this happen? Did you will it so, or was it done to you? Are you under a spell?” Green didn’t reply. Purple couldn’t tell if Green had a heartbeat anymore, or a heart.

Purple sat with Green for a long time, waiting for the pine cone to come back to life. She told Green funny stories, but the pine cone didn’t laugh. She brought Green mushrooms and berries and the very best snails she could find and laid them where her feet used to be, but the pine cone made no move to eat them. Green’s silence and stillness became unbearable. Purple pushed Green hard with her paws and cried, “What is the matter with you?” Green wobbled, then grew motionless. Purple let out a snarl that turned into a sob.

At last Purple turned to walk away, but she turned back again and again, hoping Green would make some move to stop her. The pine cone didn’t seem to care. Green made no sign that she even noticed as Purple trudged away.

Purple wandered disconsolate through the forest, the vibrant green all around only reminding the hedgehog of her lost and silent friend. Birds chittered and sang arpeggios to each other. She was silent and alone, her eyes heavy with tears. Then an owl swooped down and tried to catch her in its talons, and Purple roused herself from her sorrow and ran as fast as she could. She crouched shivering and miserable under a thorny shrub until the owl winged away, hooting imperiously. The hedgehog worried that the owl might find Green, but she wasn’t near enough to warn her. Purple hoped that at least as a pine cone, Green would be safe from the owl’s predations.

The hedgehog crawled out from beneath the shrub and looked around. She had reached an unfamiliar part of the forest. Instead of leaves and fruit, the trees all sprouted books. Some of the trees, especially the smaller, younger ones, were sparsely leaved with volumes. The more massive trees were loaded with them.

Many books had fallen onto the ground. Beneath the larger trees, the forest floor was carpeted with volumes. Purple glanced at their covers as she walked over the books. Morocco leather bindings mingled with lurid paperback covers. She idly riffled the pages of one book after another. Some books appeared pristine, while others seemed to have been well-thumbed, even underlined and annotated. She wasn’t sure if these had been read on the ground or if intrepid readers had climbed trees to peruse them. She thought some of the books might contain stories that Green would enjoy, and then she remembered her loss afresh and began to cry. Her tears fell onto the book covers, and she dried them with her paws the best she could.

One book drew Purple’s attention. It was a paperback with green leaves and purple flowers on the cover. The hedgehog nosed it open. There were no dog-eared pages, no underlines or annotations. Purple climbed inside and pulled the pages shut. She wandered the forest of letters, black trees against an off-white sky. The words sheltered the hedgehog against the pine cone’s silence. Purple called Green’s name, and it echoed off the page.

The book held the hedgehog in its paper embrace, enveloped her in its clean and slightly musty smell. It rocked her to sleep. Stories sidled through her dreams, and she thought Green might be there too, flitting among the tales. First there was the story of a mother’s deep, winter-causing grief when her daughter was stolen away to the underworld; when the daughter returned, her mother’s rejoicings brought spring to the land. Next was the story of a lover transformed into a snake, then a fire, then a lion—biting and singeing his beloved as she held on—until at last, due to her determination, he turned back into himself, and not a wordless, eyeless tree.

Purple already knew these two stories, but the third was new to her. It was the tale of an inveterate reader who died before he could read the last chapters of a gripping novel and who spent his afterlife amid the book’s characters and situations, trying to figure out how it ended. He tried out tragic endings and happy ones, endings improbable and rote, until at last he happened upon the perfect ending, both unexpected and inevitable, and he was able to rest satisfied.

When Purple woke, she wandered deeper into the maze of words, towards the book’s heart, her own heart, the world’s heart. Green was part of that, whether the pine cone knew it or not. Purple became convinced that Green did still have a heart, whether or not she had a heartbeat. The book-forest was dotted with the small shrubs of the and and and but, the great towering trees of circumstance and loyalty, the bright flame-like flowers of grief and surprise. The words were beacons. The words were companions. The words were heartbeats, urging Purple on.

She kept thinking about the final story in her dream. She thought that Green would like that story, about the reader trying to find the ending to the book. I believe that Green is still alive, Purple thought. Even if she is silent and still, we are still alive, and our story may continue if I don’t give up.

At last the hedgehog came to a clearing and saw Green. Was she still a pine cone? Purple moved closer. Green stood alone in the empty space between one chapter and the next. Her spines—was Purple imagining?—no, it was true, her spines quivered ever so slightly. Green was a hedgehog again! She looked up at Purple. Something about Green’s eyes made Purple hang back, but all of Purple’s words rushed forth to say themselves. She told Green about the owl, and the forest of books, and the three stories. “But nothing seems real unless I can tell you about it,” Purple said. “Green, can you hear me? Are you yourself again?”

For a long moment she feared it was all for naught. Then Green waddled closer to her. “Yes, Purple, I can hear you,” she said, “and I am myself again, my friend.” She told Purple the story of her imprisonment in the form of a pine cone, able to hear but not reply, able to see her friend and the forest around her, but unable to be a part of any of it. She said she had turned into a pine cone twice in the past, before they became friends.

“Why didn’t you tell me?” Purple asked.

“It was the one story I could never bring myself to tell you,” Green said. “I hoped it would never happen again. When it did, I heard you trying to reach me. I wanted to tell you not to go, but I couldn’t. It was a kind of death in life. Finally the spell ended, and I looked everywhere for you. I feared that you had given up on me and gone so far away that I would never find you.”

“I would never do that,” Purple said, reproaching herself for running from Green when her friend had needed her most.

“At last I came to the forest of books,” Green said. “I found this paperback and climbed inside. I got lost amid the shrubs of the and and and but, the great towering trees of circumstance and loyalty, and the bright flame-like flowers of grief and surprise. Finally I came to this empty space between chapters to rest, and you found me.”

Purple wept for joy. Her happiness was so intense, she felt it could bring spring to the land. Together the hedgehogs made their way out of the book and found their way home. After that, they frequently visited the forest of books, where they met other readers who ventured there. Purple and Green combed through many volumes on the forest floor in search of the most beautiful stories to share with one another. And when, in the course of time, Green became a pine cone again, Purple stayed by her side and told her stories as she waited for her friend to return to her once more.

* * *

Originally published in Lackington’s.

About the Author

About the Author

Gwynne Garfinkle lives in Los Angeles. Her collection of short fiction and poetry, People Change, was published in 2018 by Aqueduct Press. Her work has appeared in such publications as Strange Horizons, Uncanny, Apex, Through the Gate, Dreams & Nightmares, Not One of Us, and The Cascadia Subduction Zone.

The Bone Poet and God

by Matt Dovey

“Choosing your own rune is… is the act of choosing who you want to be. It’s the moment of knowing yourself and defining yourself. Of finding your place in the world. But I don’t know who I am yet.”

“Choosing your own rune is… is the act of choosing who you want to be. It’s the moment of knowing yourself and defining yourself. Of finding your place in the world. But I don’t know who I am yet.”

Ursula lifted her snout to look at the mountain. The meadowed foothills she stood in were dotted with poppy and primrose and cranesbill and cowslip, an explosion of color and scent in the late spring sun, the long grass tickling her paws and her hind legs; above that the forested slopes, birch and rowan and willow and alder rising into needle-pines and gray firs; above that the snowline, ice and rock and brutal winds.

And above that, at the top, God; and with God, the answer Ursula had traveled so far for: what kind of bear am I meant to be?

She shouldered her bonesack and walked on.

* * *

There was a shuffling sound among the bracken, small but definite. Ursula hesitated, a dry branch held in her paws, her campfire half-built. Ambush wasn’t unheard of—so many bears sought God on the mountain that bonethieves couldn’t resist the chances to steal—but it had not been so large a sound, and she couldn’t smell another bear beneath the pine scent. It was something smaller, lurking in the dim light of the forest floor, behind the massive rough-barked firs that filled the slope.

“Hello?” she ventured, still holding motionless. “It’s quite all right. I’m building a fire, if you’d like to join me.”

A badger stepped out from the ferns, his snout twitching and cautious, a stout stick held warily in his paws. He eyed Ursula for a moment, weighing up the situation, and she gestured ever so gently to the fire she was building, trying to come across as safe, as friendly. As likeable.