Feed aggregator

Interview With Posso - South Bronx, Cultural Differences, & Twitch Streaming

Resources, Social Media & Donation Links

Follow Posso

Join Rhyner's Telegram Channel

On August 30th I sat down with a buddy of mine Posso - addressed as Storm in the interview - to discuss his roots and passions. Growing up in the South Bronx as half Dominican and half Puerto Rican Posso recounts his experiences growing up in "the hood."

The dog eat dog nature of his surroundings taught him to put a mask on. But as he grew older, he came to terms with who he really was and embraced being part of the LGBT+ community and started a support system by steaming Smash Bros. Ultimate on twitch.

Though he's furry adjacent, he's got more than a few choice words to say about the furry community...

Thanks for listening!

TigerTails Radio Season 12 Episode 38

Issue 8

Welcome to Issue 8 of Zooscape!

Tentacles, talons, and fins… these stories speak for themselves.

* * *

A Wake for the Living by Jordan Kurella

Swift Shadow’s Solace by E.D. Walker

Source and Sedition by Koji A. Dae

The Starflighter from Starym by Tamoha Sengupta

A Bitter Thing by N. R. M. Roshak

Keep Breathing by Karter Mycroft

Cepha by Eliza Master

Dinos on Your Doorstep by Nina Kiriki Hoffman

Philosopher Rex by Larry Hodges

* * *

As always, if you want to support Zooscape, we have a Patreon. Also, we are once again open for submissions!

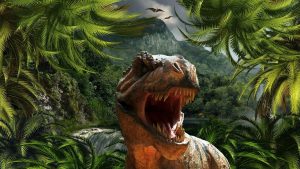

Philosopher Rex

by Larry Hodges

“The hunger pangs returned two days later, meaning death to another duckbill or some other wretched creature. Damn the system.”

“The hunger pangs returned two days later, meaning death to another duckbill or some other wretched creature. Damn the system.”

The T-Rex stared down at the duckbill he’d just killed. He was sorry for the harm he had caused it, but what choice did he have? He took the first chomp out of it — but it only made him more ravenous. Sometimes at night he’d stare up at the stars and wonder what monster had created this evil predator-eat-prey system. But it was eat or die.

The duckbill was large enough to feed him for two days. Good. Tomorrow he would hunt down another duckbill, and then let it go free, cheating destiny and fate. He longed to play with the duckbills, but while he didn’t mind playing with his — and he snorted in disgust — food, the food had other ideas, despite his tiny arm-waving assurances. He’d even tried joining them in grazing, but the plants they ate were the worst thing he’d ever tasted and gave him a stomachache that lasted a week.

Loneliness. There were other T-Rexes, but they were brutes, interested only in killing, eating, and killing. If the other T-Rex was larger, it would attack him; if it were smaller, it would run away. Sometimes he’d play with a rather dense Ankylosaur he’d adopted, playfully shoving at its shell while dodging its clubbed tail. But that got rather old, and he wasn’t sure if the Ankylosaur enjoyed the game.

The hunger pangs returned two days later, meaning death to another duckbill or some other wretched creature. Damn the system. Maybe he’d have a fight-to-the-death with a Triceratops — that always brought a thrill, followed by guilt.

The hunger drove him to hunt again. He plodded silently through the forest, sniffing the air, scanning the forest for movement, and listening intently for low-frequency sounds of distant prey on the move. His mottled brown feathers camouflaged him from prey right up until the final lunge. He was a pure hunting machine, and both proud and embarrassed by this. He sometimes watched the ripples from his passage in nearby puddles and wondered what others felt like knowing he was nearby. It must be terrifying.

He caught the scent of a group of furries, but knew they were small and underground, and not worth digging out. He saw a colorful, winged insect in his path. He carefully stepped over it, not wanting to destroy its beauty.

A small tunnel beneath his feet collapsed. A dozen furries scattered in different directions on their four legs, whistling cries of distress. He dropped a clawed foot over one of them, caging the poor, tiny, squeaking creature. Then he lowered his massive head for a better look at the convenient snack. Poor thing. The creature fought valiantly but with utter futility against the unyielding foot of the T-Rex. He could easily crush it but hesitated as he watched the creature struggle.

It finally tired and stopped struggling. It stared up at him, breathing far too rapidly and shaking with fright. Fine fur covered its body, brown with a white belly, with a long, quivering snout and even longer, skinny tail. Its eyes were huge, shaped like giant teardrops. They looked up at him from between his giant toes, and there was something there, a spark he rarely saw in others. Other T-Rexes had that spark, but they were angry ones that glittered warnings. He could see the intelligence in this furry’s frightened eyes.

How could something so small and so defenseless survive? Even its tunnel wouldn’t protect it from a determined predator, which could tear it apart in seconds. And yet, somehow these creatures survived, the underfoot of the world.

Slowly the creature’s breathing slowed and the shaking stopped. It leaned back on its haunches, freeing its front legs — with tiny hands — as it stared up at the T-Rex, wiggling its whiskered snout, perhaps resigned to its fate. What fate would that be? It had to be smart, to survive with so little. Maybe there were dumb ones, not smart enough to survive. If only the smartest survived, perhaps they would keep getting smarter. Where would it end?

There was a sudden symphony of squeaks, and he felt something sharp and vaguely painful in his legs. A pack of the little creatures were attacking him, biting him with their tiny teeth. He watched, bemused. What must it be like to be so small and weak?

Then he felt a much stronger jab in his free foot. One of the furries was attacking him with… a stick! It jabbed the pointed object into his foot over and over and it actually hurt. He gently kicked the creature away, perhaps too hard as it went flying through the air, dropping the stick. The other furries continued biting him, but he ignored them. The T-Rex stooped down and examined the object. It was like teeth for those without large ones. He’d never seen a creature use an object like that. This one must be smarter than the others of their kind. Perhaps they had a future, or at least the ones related to that one.

But teeth last forever while a wooden stick would snap with a tap of his claws and then rot away. He could probably kill or daze all of them with a yank of his foot, sending them flying, and then pop them into his mouth, one by one. But such bravery and devotion!

The trapped one still stared at him with its intelligent eyes. He’d have to find other prey. He raised his foot. But the creature continued to stare at him for a moment before it finally stepped free. The others stopped their attack, also staring at him. Then they all scampered off.

Late that night the T-Rex stared up at the stars and moon, wondering what they were. What kept them in the sky? What caused their light? Why did they go away during the day, replaced by the fiery sun? These were things he could experience but never solve, and maybe that was more important.

But often he just watched the little creatures that no longer avoided him, keeping him company as their small ones played on his gently swooshing tail. And they, down on the ground, were of course no threat to him, no more so than the stars in the sky.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

Larry Hodges is an active member of Science Fiction Writers of America with over 110 short story sales and four novels, including Campaign 2100: Game of Scorpions, which covers the election for President of Earth in the year 2100, and When Parallel Lines Meet, which he co-wrote with Mike Resnick and Lezli Robyn. He’s a member of Codexwriters, and a graduate of the six-week 2006 Odyssey Writers Workshop and the two-week 2008 Taos Toolbox Writers Workshop, and has a bachelor’s in math and a master’s in journalism. In the world of non-fiction, he has 17 books and over 1900 published articles in over 160 different publications. He’s also a professional table tennis coach and claims to be the best science fiction writer in USA Table Tennis, and the best table tennis player in Science Fiction Writers of America! Visit him at larryhodges.com.

Dinos on Your Doorstep

by Nina Kiriki Hoffman

“Either change everyone else into dinosaurs, or change us into something else,” said Big D. “Something people would expect to see.”

“Either change everyone else into dinosaurs, or change us into something else,” said Big D. “Something people would expect to see.”

You know you’re in trouble when you have dinos on your doorstep. Not just because they’re extinct. They’re also clawed, scary, and they make you regret messing with that time machine, because introducing anomalies in your own time stream never ends well.

“Carson Wheeler?” said the feathered Deinonychous at my door. Her voice was raspy and came out of her throat instead of her mouth. She wore what looked like a police uniform, though I didn’t know the language or writing on her badge. She had a lot of teeth in a head shaped like a football with one end split open, with a feathered crest at the other end, and large amber eyes in the middle. Her bare back feet had one upraised scimitar claw on each, sharp and capable of disemboweling squishy beings like humans.

“Uh?” I said.

She poked me in the chest with a long, curved claw. “Are you Carson Wheeler or aren’t you?”

“Uh,” I said, “maybe?”

She poked me twice more, hard enough to bruise, but she didn’t stick a claw in me to see if I was done.

“How is that a maybe question?” she said.

A smaller dinosaur peeked out from behind her. It had been under her outstretched, feather-edged tail, which was as long as I was tall. The tail looked like it could whip over and knock me off my feet. Admittedly not much of a challenge.

The little one looked like a smaller version of the big one. It was about the size of a Thanksgiving turkey for a family of ten, and it wasn’t wearing clothes. Wing-feathers edged its upper arms and stubby tail, and it had a little crest. I wondered if it was the big one’s baby. Maybe in Dino culture they did that sort of thing, take your dino daughter to work?

“Carson Wheeler,” it croaked, in a deep voice like rusty gears engaging.

“What can I do you for?” I asked, cleverly still not admitting who I was.

“You can change,” said Deinonychus.

“Uh?” I said.

“You brought us here,” said the little Velociraptor. “Fix it.”

“Either change everyone else into dinosaurs, or change us into something else,” said Big D. “Something people would expect to see.”

“I don’t think I can do that,” I said. “What if I could just send you back where you came from?” I wasn’t sure I could even manage that. The machine had just showed up in the basement right next to my gaming console. Naturally I fiddled with it, even mapped out some of its capabilities. It had jumped me ten seconds into the past, and ten seconds into the future, which was weird, because the first time, there were two of me in the basement, and the second time, I went away and didn’t exist, but I came back. There were buttons I hadn’t touched yet. I was taking it slow. I thought.

Baby V came forward and clamped his jaws around my right calf. The teeth pressed into the denim of my jeans. “What if I bit off your lower leg?” he asked.

How could he even talk with his mouth full?

“Yeah, no, that wouldn’t be good,” I said. Had Mom left any meat in the fridge? Maybe I could decoy them with hot dogs?

Big D poked me in the chest again. “Fix it.”

Little V unhinged his jaw and released my leg, but I could see him eyeing it. He had tasted denim and he wanted more.

“I don’t — I’m not — I — ” I glanced over my shoulder. Mom had gone to work about an hour ago. I was supposed to be heading to high school right now, but the new machine. . .

I stood back and held the door open. “How did you find me? What makes you think I had anything to do with this?”

“The particle trail,” said Big D.

“My name?” I asked. I mean. I live with my mom. I’m sixteen. My name’s not even on our mailbox, and Mom has a different last name.

Big D shoved past me into the house, leaving a stench like the inside of a mouth when the teeth hadn’t been brushed in two days, and Little V followed her, slapping me in the crotch with his wing arm. Mega ouch! I hunched over with my hands over my crotch and waited for the hot, pulsing pain to pass. It took a while. I had my eyes tight shut, and tears ran down my cheeks.

“Interesting,” said Big D.

“Didn’t know it would do that,” said Little V.

“Good weak spot.”

When I could open my eyes again, I stared at their bare dino feet on my mom’s pale blue shag carpet. They had those sticking-up claws instead of big toes, and only two other toes besides. With scary black claws on all three toes.

I pulled myself up straight and swiped the tears off my face, feeling embarrassed and angry. Look on the bright side: had to be glad Little V hadn’t clawed me, anyway.

“Are you at capacity again?” asked Big D. She twisted her head and looked at me with one golden eye, then the other.

“No,” I said, and groaned.

“But you can show us the machine.”

“Yes.”

I edged around them, watching Little V’s wing-arms. He kept them still, though a little purring growl rolled in his throat. I got past them into the living room. “This way. Try not to knock anything over,” I said, and that was probably a mistake, too. Why was I giving them ideas?

But they picked through the living room without destroying anything, and followed me through the kitchen and down the basement stairs.

To where I lived most of my life when not compelled to go outside by things like school. Mom had let me move down into the basement last year, so I could practice guitar without driving my older sister Kayla buggy, and play my games on the big gaming computer in the rec room. It was dark down there, and that was how I liked it.

“You featherless bipeds are stinky,” said Little V.

Yeah, I should probably wash the couch cover and change my bedsheets. But nobody else came down here anymore since I moved into the rec room and Dad got a 42-inch TV in the living room. I cracked a window.

“There it is.” I pointed to the new machine that had arrived late last night while I was kind of dozing with my headphones on and the controller in my hand. One minute I was shooting other soldiers in ruins and sneaking around, and then, well, there were probably a few blank minutes, because I woke up dead, and noticed this stack of three pale egg-shaped nodules with glowing buttons scattered here and there on them. I peeled out of my game gear and went over to look at it. Some faint writing near the buttons that looked like a Star Trek alphabet, not anything I’d seen on Earth. I took some phone pics of it and sent them to my game buddy, Frank. He thought I had built it out of eggs and wouldn’t take it seriously.

This morning, when I got up off the couch where I had crashed, I pressed one of the glowing blue spots. And then the doorbell rang.

Come to think…what would Frank think about dinos in my house? I pulled out the phone and aimed it at them to snap some pics.

Little V jumped up, grabbed it in his three-fingered hand, and bit down on it. It crunched, and he spat out pieces of glass. “Awfg! That’s the worst tasting food bar I ever ate!” He went ahead and swallowed it, though.

My phone! What was I going to do without my phone?

Big D went to the new machine and sniffed it all over, loud breaths sucked in through her nostrils. “You touched it here?” she asked, pointing a claw toward the button I’d pushed.

“Yeah,” I said.

She tapped it with a clawtip.

The world crushed in on me. I felt like I was being whomped by a potato masher from all directions at once. The pain was so excruciating I just — let go, falling down into darkness.

When I opened my eyes again, everything looked different. My nose pushed out in front of my eyes, and it looked more like a dog’s muzzle than a nose.

The light was too bright, the edges too sharp. I had to blink a bunch to realize I was staring at the ceiling of my basement room, which was basically gray with a lot of cobwebs stenciled across it, thicker in the corners. They looked like lace now.

And cowabunga, did everything smell different! Scents were flooding into my nose as if pouring in through two funnels, and it wasn’t pleasant. My tennis shoes in the corner reeked. The clothes scattered across the easy chairs and even the ones I’d managed to get in the laundry hamper, which I used as a basketball hoop, stank. On the other hand, the pizza crusts I’d left under the table two days ago smelled like fresh bread and ripe tomatoes, and I was hungry.

I sat up and noticed, yeah, where were my arms and hands? I waved my arms, and stubby wings waved instead. My big toe claw had torn right out of my tennis shoes, and my clothes were stretched and torn, hanging off my feathered body in rags.

“Well, that worked,” said Little V.

“In a way,” said Big D.

I tried to stand up, and then big muscles near my butt activated my new tail. My clothes pretty much fell off me, which would have embarrassed me if I weren’t covered with feathers. I swished my tail a couple of times and found my balance.

The other dinosaurs had a musty, earthy smell. Big D looked…smelled…like something I wanted, in a gush of hormonal rage. I lurched toward her and she laughed and fended me off with a wing-arm. “Not so fast, Junior. Let’s see if everything’s fixed first.” She headed back up the stairs, Little V trailing after, and me learning how weird it was to walk up the stairs with three-toed feet when one of the toes never touched the ground.

Big D went right through the living room and out the front door, and we followed her.

Mrs. Holiday — maybe — stood across the street, watering her vegetable garden with a hose. I mean, she wore the kind of flowery sun dress Mrs. Holiday wore in real life and in my fantasies, only she wasn’t a teenage boy’s dream neighbor anymore.

Her little wing-arms flapped and she tossed the hose away from her and let out an ear-splitting shriek.

“Well, that went well,” said Big D. I lifted my snout. Somewhere nearby somebody was cooking sausage.

I headed out in search.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

Over the past thirty-odd years, Nina Kiriki Hoffman has sold adult and young adult novels and more than 300 short stories. Her works have been finalists for many major awards, and she has won a Stoker and a Nebula Award.

Nina’s novels have been published by Avon, Atheneum, Ace, Pocket, Scholastic, Tachyon, and Viking. Her short stories have appeared in many magazines and anthologies.

Nina does production work for The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and teaches writing. She lives in Eugene, Oregon. For a list of Nina’s publications: http://ofearna.us/books/hoffman.html.

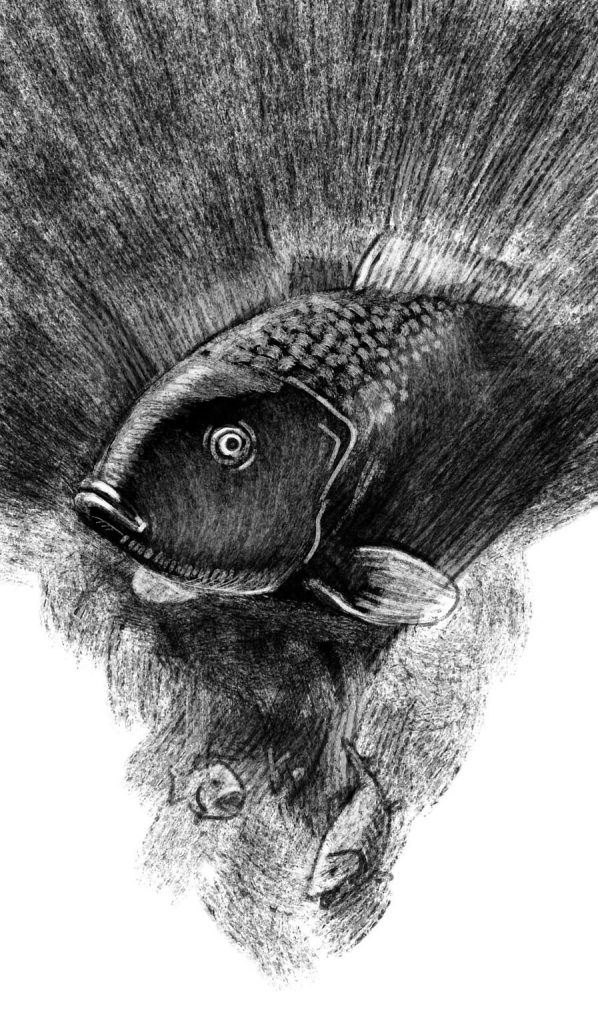

Cepha

by Eliza Master

“She had planned on following in her mother’s tentacles, but she was too sad to try.”

“She had planned on following in her mother’s tentacles, but she was too sad to try.”

Cepha’s mother Octavia was harvesting algae when she got caught in a net made by humans. It dragged the octopus upward and out of the ocean. Underneath, a school of smelt watched. The youngest fish, Osme broke away from her siblings and rushed to report the sad news. Cepha was heartbroken. She puffed out a cloud of black ink in sorrow.

As news of Octavia’s death spread, many fish visited Cepha’s home as if it were a museum. Cepha showed them her mother’s office. The ceiling was made of pink coral and the walls were coated with yellow sea moss. Inside were piles of crystalline sand and jars of brown algae-glue. She explained how her mother used a swordfish blade to remove rotten fish fins caused by human garbage. And how she developed a three-tentacle sewing technique to attach replacements. Cepha always finished by saying that the new fins were as flexible and as strong as the originals.

After a while there were no more visitors. Cepha had no one to talk to. She spent her days listlessly inside watching the current. Crustaceans, starfish, and fish drifted by. She had planned on following in her mother’s tentacles, but she was too sad to try.

One bright morning Osme flipped her tail against Cepha’s coral gate. Cepha came out to greet her. Osme had grown and her belly was fat with eggs. There were several male smelt lurking around. Cepha opened the gate and locked it behind her.

“I’m scared,” said Osme, as she darted into the sandy courtyard.

“Are they following you?” asked Cepha. Osme’s fins looked strong, but her eyes were glazed over, and her scales had lost their shimmer.

“They say they will escort me out of the ocean to a clear river where we can hatch eggs together.” Cepha and Osme both knew that smelt females died after egg lay. Gingerly, Cepha wrapped a tentacle around Osme’s swollen belly. Her skin was so tight that a long red mark was forming under her gill. No wonder her friend was frightened.

They came up with a plan. Cepha swam into her mother’s office and Osme followed. Cepha fetched the swordfish blade from the coral shelf. She reached out her tentacles for a spool of kelp thread, algae glue and a sea sponge.

“Are you sure?” she asked the smelt.

“Yes, I’m sure,” Osme replied, meeting Cepha’s gaze.

Cepha used the blade to make a small incision in Osme’s belly. Gently, she pushed out the eggs. They floated away. Then she cleaned the area, applied algae glue and stitched it together with three tentacles the same way her mother had done. The procedure only took a few minutes.

“Does it hurt?” she asked.

“Not one bit,” Osme replied, her eyes brightened. They shared some delicious seaweed chips. When Osme left, the male smelt were gone.

Word got around on the reef. Many female smelt came to Cepha’s for help. They gave her shell ornaments and sea fruit in appreciation.

One evening Osme brought a big school of smelt to visit. They were a mix of males and females, some with a small scar from Cepha’s work. Delicate bubbles floated from their giggling voices. They told her that there was a new octopus living beyond the reef. He was a surgeon like Cepha and her mother. They said he’d set up shop in the blue area, deeper down.

Cepha decided to visit the new octopus right away. She swam out of her den and descended along the ocean floor. The sand was larger here than in her neighborhood. It wasn’t long before she saw a house made of staghorn coral. Its pillars were an elegant ivory attached to a pile of grey boulders. The big octopus squeezed out to greet her.

“I’m Topus,” he said. “I’ve heard a lot about you.”

“Nice to meet you,” replied Cepha. Topus was the first octopus she’d seen since her mother died. She couldn’t stop staring. His black stripes were handsome, and his eyes were the color of sea grass. She flushed. Hopefully he didn’t notice. Topus told her about his cure for shellfish bleaching. The two octopi talked all night.

As Cepha prepared to go home, Topus presented her with a bracelet made from gold pearls. “I want you to have this. It was my grandmother’s.” He wrapped the bracelet around her front left tentacle. Topus’ suction cups sent a pleasing sensation into both of her hearts. Cepha wanted to touch his velvety skin. But instead she pulled away.

Respectfully, Topus withdrew his tentacles and folded them underneath. His stripes dimmed.

“Please come visit again,” said Topus.

“I will and thank you,” she replied.

The golden pearls on her left front tentacle sparkled the whole way home.

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

Eliza Master began writing with crayons stored in an old cookie tin. Since then, many magazines have published her stories. Eliza’s three novellas, The Scarlet Cord, The Twisted Rope, and The Shibari Knot are soon to be released. She attempts to make each day better than the previous one. When Eliza isn’t writing you can find her amongst brightly colored clay pots dreaming of her next adventure.

Keep Breathing

by Karter Mycroft

“The census never stops, not when the finless move around as they do.”

“The census never stops, not when the finless move around as they do.”

The finless must go down. Those are the words. The Agent mutters them to herself as she wades through the murk, reaches the door, knocks and waits. She repeats them, aloud this time, when the rock slides open. A young one, shimmerwhite with brilliant pink wings.

“Indeed they must,” he says, nodding at her badge. “You’re with the census?”

“I am. How many have you got?”

He stands up straighter, backs away from the threshold. “I live alone. You’re free to have a look around. Anything you need.”

She glances past his shoulder into the mudcave. It is small, well-adorned with shell and bone, the home of a young professional. And a true believer, by the look in his eyes. The type who’d love nothing more than to contribute to ridding the world of deviants and blasphemers. She nods. “No, that won’t be necessary. Enjoy your afternoon.”

Back through the mud to the next residence. Her twentieth today. The census never stops, not when the finless move around as they do. The next home is rocky and crusted with mussels. She slaps the door until it rolls aside to a nervous greeting. An old puckerscale with sad eyes and a tremor.

“The finless must go down.”

“Whyyesofcourse.”

“How many have you got, uncle?”

His answer is all shivers. He glances down. “Only me.”

She lengthens her fingers, stretching her webs. “Would you mind showing me inside?”

Panic oozes from his nod. She glides in, scans the foyer, takes a deep breath. She can smell others already. She follows the stench to a crevice of hushed voices, concealed behind a leafy curtain. Three of them. Adolescents. Two with ruby red neckwings, healthy and breathing. Both clutching the third, a girl with pallid skin whose neck is all stumps. All of them frightened.

Everyone protests at once. “It isn’t how it looks.” “Please, have a heart.” “You can’t take her, you monster.” “We don’t know her, she just showed up here.”

Only the girl is quiet.

“What’s your name?”

Silence.

“Please don’t make this difficult. ”

Reluctant glances, a twitch, and then—”Dry.”

“What’s your real name, Dry?”

“I only have one name.”

The Agent pulls Dry into the hall. The nubs on either side of her neck are still wrapped, swollen red around tight bindings that would have cut off circulation to the precious appendages. Freshly sloughed, by the looks of them. She would start to change before long.

The old man stands between them and the entrance. “Please,” he starts to say. “Don’t take her. She’s only done what she thinks is right.”

The Agent fingers the spear at her waist. She could arrest him as well, for lying and abetting and harboring. She is practically required to. She brushes past him into the murk.

* * *

It’s slow going. With her arms cuffed, Dry can only manage by squelching along the clayfloor. It’s a bad weatherday, foggy with silt. Forecast says no clearness until the weekend. They catch no eyes as they amble toward the Department. There it is, now, a hazy outline of sunken rotwood, the ruins of a great tree, pocked with tunnels. A security duo float outside the main swimthru, armed and watchful. The Agent pauses at the gurgle of Dry’s voice.

“I know what you’re gonna do to me.”

“Do you?”

“Yes. We all know. You’ll shut me in a room in the dark until I beg to get out. Until I am nearly done changing and can hardly breathe. Then you’ll wait longer. You’ll ask me questions. Who recruited me, where the others are. You’ll hurt me when I answer but hurt me worse when I refuse. Then you will weight my legs and send me over the dropoff, as far down as down goes, where I will drown alone in the dark.”

The Agent glances at the Department and then at Dry.

“That is not what I will do.”

Dry stomps the clay. “Why lie? We know the law and we know we break it. We accept the risks and the consequences. Alone we may be hunted, broken, made examples of, but together as one we are solid stone. We’re not afraid of you. We keep breathing.”

“You are not afraid? ”

She can tell by the way Dry’s eyes dart around, by the way her tail shivers, that she is in fact deeply afraid, her fear seeping through layers of righteous anger.

“I don’t want to die, if that’s what you’re asking.”

“I would imagine not.”

“But if we don’t change we will die anyway. All of us. The lake is shrinking, the water goes to the sun and wisps away. Everyone can see it, yet no one speaks of it. There is no future for us down here, only doom.”

“And you think you’ll be safer above?”

Dry’s response chokes in her throat.

The Agent takes a deep gulp. To reject the mud, forsake the congress of one’s own birth, to mutilate oneself into a metamorphosis that should be lost to time, all for a fleeting chance of a better life above. To die for a suicidal cause. Stupidity and courage, those longtime lovers.

“Come with me.”

She grabs Dry by the cuffs and starts toward the Department. Past security scowls, into the swimthru, round the sludgepainted halls to the stocks. She can feel Dry’s heart race faster the deeper they go. They reach an open cell at the end of the hall, its walls coated in menacing black slime, barely wide enough to imagine Dry fitting into. The Agent peels back the rock opening.

“In here.”

Dry panics. All the composure and indignation vanishes when she sees the darkness and she tries to suck free, strains to wrest the cuffs from the Agent’s grasp. The Agent holds her steady, wrangles her into the crevice, ignores her gasps of protest and the sobs that leak out after. She slides the seal back into place.

With an inch left to go, she bubbles out a whisper. “Listen close. In the farback under your toes, a stone will come loose. If it doesn’t, pull harder. Beyond you will find a very slim tunnel, so slim only the finless can use it. Scrape all the way through and you will arrive many pools to the east. From there, seek above.”

Dry begins to balk, to question, to disbelieve. They always do. But there’s no time to explain. The Agent rolls the stone shut. One whisper must suffice. “Keep breathing, sister.”

She has a good feeling about this one, though she can never be sure if anyone makes it. Possibly no one has. But it’s an effort worth making, if anything is. She may not be brave enough to change herself, but the finless are right: the lake is leaving them. The Department’s suicidal adherence to tradition will change nothing. They must learn to live above or die forever.

She returns out of the prison labyrinth to the main swimthru. Back out to the census. She hopes she can find the next one before her colleagues do. She isn’t sure she can bear to watch another sinking.

The security duo wait at the exit. A chill in the mud. They are facing her, fins wide with agitation.

“Everything all right?”

A splash behind her. More guards. Spears at her neck. Cuffs at her wrists. A blow to her head. Darkness.

* * *

She thrashes in the dark, helpless in her bonds. A voice asks for names.

“I acted alone.”

A searing, serrated pain at her neck.

“Names.”

“No!”

“You accept full responsibility for every escape since you became a census-taker?”

“Yes!”

“You worked with no one?”

“No one!”

“I see. What were their names?”

More pain, so much she can no longer speak. The stench of blood fills the muck.

“Please. Please don’t.”

“What? You wanted to help them so badly. Why not be one of them?”

Pain. So much pain, colors jolt before her eyes. So much pain she calls out to her dead mother for help. So much pain she falls asleep.

* * *

When she wakes, she is standing on a ledge. At her sides, mud turns to smoke, mixing and dissipating into something blue and infinite and very, very cold. She looks down and sees two heavy rocks strapped tight to her feet, and below them, a steep drop into abyss. She looks behind her and sees the entire congress gathered—her colleagues, the guards, the young man and the old uncle with his grandkids. All watching her. Some laughing, some scowling, some with furtive glances of what might be solidarity or nothing at all. The pain on her neck is unbearable; the sensation of trying to move limbs that no longer exist is worse.

It is difficult to breathe. She twitches her neck in a panic, but only a trifle of breath tickles her insides. Her change is already beginning. She feels a strange, desperate need to get out of the mud, to go upward and outward, to suck air into her mouth and taste the outside and all the life it may bring. She can’t move.

She wonders if Dry made it. Supposedly a community of finless has established inland from the lake. If Dry found them, she might be all right. A new world of wind and sun, a world of untold dangers, but a world fighting for hope instead of against it. Hadn’t that been why she helped them escape? For hope? Was there even such a thing? Yes, yes, of course, she tells herself. Always, even in the darkest days of a vanishing world, there is hope.

But none for her.

Something presses on her back.

The voice from the dungeon calls to the crowd: “The finless must go down!”

* * *

About the Author

About the Author

Karter Mycroft is a writer, editor, musician, and fisheries scientist who lives in Los Angeles. They write on the beach by asking the dead fish for ideas. Their short fiction has appeared in The Colored Lens, Coppice & Brake, Lovecraftiana, and elsewhere. You can find them on Twitter @kartermycroft.

A Bitter Thing

by N. R. M. Roshak

“But O, how bitter a thing it is to look into happiness through another man’s eyes.”

—Shakespeare, As You Like It (V.ii.20)

“Were people really eating octopus to express their resentment at the hexies’ presence?”

“Were people really eating octopus to express their resentment at the hexies’ presence?”

I should have known that something was wrong when I found Teese in the back yard, staring at the sky. It was sunset and the horizon was a particular shade of pale teal. At first I thought Teese was just admiring the sunset, but then I realized he was trembling all over. His eyes were wide, and irregular patterns swept over his skin, his chromatophores opening and closing at random, static snow sprinkling his skin.

I touched his shoulder. “Are you all right?”

Above us, the sky darkened toward night. Teese shook himself like a dog, blinked, looked at me. “That sunset,” he said. “We don’t—these colors—This doesn’t happen on our world.”

“You don’t have sunsets?” As I understood it, sunsets should happen anywhere there was dust in the air.

“No, no,” he said. “Of course we have sunsets, Ami, but they tend more toward the red side of the spectrum. Your planet is so rich in blues. These colors, they’re not very common on my world. I suppose I was surprised by my reaction to seeing that particular shade of blue spread across the sky.” He smiled down at me. “Anyway, it’s all changed now. Fleeting as a sunset, isn’t that the expression?”

Teese was back to his usual smooth articulateness, so I wrote it off as his being momentarily overcome by the Earth’s breathtaking beauty. In retrospect, that was pretty arrogant and anthropocentric of me. But at the time, I thought: who wouldn’t be struck dumb by my amazing planet?

* * *

That night, Teese stared deep into my eyes as we made love, and trembled, just a bit. Static flared across his cheeks as he came. His heart-shaped pupils flared wide, drinking me in, and he murmured “I could stare into your eyes forever.”

So of course I thought we were all right. We were all right. However unlikely, however improbable, what could it be but love?

* * *

The next warning sign came weeks later, when Teese painted the linen closet blue. He moved out all the towels and sheets, took out the shelves, painted the walls (and the ceiling, and the back of the door) greenish-blue, and perched on a stool in the middle of the closet. He called it his “meditation closet,” jokingly, and said that he went in there to relax. At first it was for minutes at a time, then slowly his “meditation time” grew to hours.

“The things your people do with color are amazing to me,” he said. “So many colors, and you put them everywhere.”

“What, you don’t have paint where you come from?”

“Of course we have paint,” he said. “But we use it for art. No one would think to put gallons of blue and green in cans for people to take home and spread all over their house. It would cost—” He paused. Interstellar currency conversions were impossible, finding correspondences of value almost as difficult. “Many years of my salary, I think, to paint just this closet.”

“Well, that makes sense. If you went to an art supply store here and got your paint in little tiny tubes, it would cost a lot more here too.”

“And the colors,” he continued. “I think I have told you that most of our colors are in reds and browns and oranges. Even in paintings, we don’t have so many shades of blue.”

“That’s weird,” I said. “I mean, you can see just as many shades of blue, right?”

“Yes, but—” He considered. “Ami, I think that you have so much blue that you don’t see how it surrounds you. You can make a painting with a blue sky and blue water, and use one hundred different shades of blue, and everyone sees it as normal and right. But think of another color that you don’t have in such abundance, like purple. Imagine a painting with nothing but one hundred shades of purple.”

His words triggered a memory. “I actually had a painting like that once,” I admitted. “I found it in the trash in college. It had a purple sky and a purple-black sea and two really badly painted white seagulls. It was so awful that I had to keep it.”

Amusement fluttered across his skin. “Tacky, right? Well, that’s what most of my people would think of your sea and sky paintings. But I love it. I love to be surrounded by blue.”

“Meditating?”

He waved an arm noncommittally. “Ommmm,” he said, brown fractals of laughter flashing across his skin.

* * *

Then Teese bought one of those fancy multi-color LED lightbulbs, tuned it to the exact shade of the walls, and didn’t come out for a day.

He was in the closet when I left for work, and still there when I got home. I tapped on the door—no answer. I told myself to give him his space and went about fixing dinner, even though it was his turn to cook. Teese’s diet was similar enough to ours that we could cook for each other, though there was a long list of vegetables he was better off without. I knocked on the door when dinner was ready and called his name. No answer. I ate without him.

Later, I pressed my ear against the door but heard only my own heartbeat against the wood. It was dark by then, and blue light seeped out from under the door.

Finally, I eased the door open a crack and peeked in. Teese was sprawled on the floor next to the upturned stool, eyes vacant, skin utterly blank.

I yelled his name, shook him, even slapped his face. My fingers shook as I pressed them urgently into his skin. I remembered that Teese had two hearts but I couldn’t remember where they were, or how to find his pulse. There was no one I could call, no doctor or ambulance who could help him. I was alone with Teese and Teese was gone, sick, maybe dying.

I dragged him out into the hallway, slowly. Teese doesn’t have any bones to speak of. He’s all head and muscled limbs. Normally he holds himself upright on four powerfully muscled limbs and uses the other two like arms. Passed out, he was a tangle of heavy rubber hoses filled with wet cement. I had to pull the blanket off the bed, roll him onto the blanket and drag the blanket out of the closet with Teese on it.

I stood over him in the hallway and felt terribly alone.

* * *

I had met Teese at a party I hadn’t planned to go to. At the last minute I’d let myself be swayed by the rumours that one of them would be there. A so-called hexie. Their ship had landed months ago, and while the VIPs on board were busy hammering out intergalactic trade deals, most of the ship’s crew were just sailors who wanted to get off the ship, get drunk, and maybe get to know some locals. They’d been showing up by ones and twos at bars and clubs and parties all over town. I’d seen the hexies in the news, heard about their appearances at bars and parties, but never met one in person. And like everyone else, I was curious.

I saw him the moment I stepped in the door: big head held up above the crowd, two long and flexible arms gesticulating, one of them holding a drink. His eyes swept the room, scanned over me, and snapped back. From there, it was like a romance novel, of the kind I’d always found tedious and unrealistic. Our gazes locked. He stopped mid-sentence, handed his drink to someone without looking, and started pushing his way across the room to me. My heart hammered in my chest. Of course I couldn’t take my eyes off him, but why was he staring at me?

He stopped in front of me and took my hand, coiling his powerful armtip around my fingers as gently as I’d cradle a moth.

“I am Teese,” he said. “Forgive me for being so direct, but I have never seen eyes as beautiful as yours before.”

Hackneyed words, but they sounded fresh coming from his lipless mouth.

“I’m Ami,” I stammered. “And I’ve never seen anything like you either.”

Orange and brown checks rippled across his face. Later I would learn that this meant interest, arousal, excitement. I let him lead me to a quiet corner.

We talked. He told me about his ship, the long watches tending to the cryo boxes, the vastness of interstellar space. I told him about my job at the Citgo station and my apartment and the time my cat died.

“When I look at you,” he said, “I feel things that I’ve never felt before.”

What else could I do? I took him home, and he stayed.

* * *

Now I was alone in my hallway with Teese unconscious. I stepped around his arms and closed the linen closet, and sat down on the ground next to him. Soft blue light leaked out from under the closet door. I turned on the hall light and turned off the closet light, for lack of anything more constructive to do. Then I sat down on the ground next to him and wondered what to do. Smelling salts probably wouldn’t help an alien from another planet, had I even had any to hand.

I could sprinkle water on his face, but I had no idea if that would work on him. I could pinch him.

I could sit next to him and stare at his open, blank eyes and wish I’d thought to ask him for a way to contact his ship.

I could search his things for a way to contact his ship, but I didn’t want to go there if I could avoid it. Teese had been living with me for two months, which is both a long time and not long at all, and as far as I could tell he’d never gone through my closet or papers while I was at work. I owed him the same respect.

Teese stirred sluggishly on the floor next to me.

I leaned over him. “Teese?”

His eyes focused on me. “Ohhh, Ami,” he said, half moaning. And then his skin was suddenly, completely covered in violently red spots. Across his face, all up and down his arms, from the dome of his head to his armtips, he was covered with hexagonal measles that shifted and spun.

Teese’s emotions showed on his skin, but I had never seen this one before, never seen such a violent and complete display.

I laid a gentle finger on his cheek, trying to pin one of the spots under my fingertip. “Teese,” I said. “I don’t know this one.”

Teese looked at me for a long moment before replying.

“Shame, Ami,” he said. “It is shame.”

Teese’s people feel emotions the moment they see them. If I’d been one of Teese’s people, I would’ve been flooded with shame the moment I saw the red blotches on his skin, and a paler echo would have bloomed on my own skin. It’s beyond empathy: it’s instant and direct and irresistible. If I’d been a hexie, I would have said: “Why are we ashamed?”, while my skin and emotions thrummed in synchrony with his.

But I wasn’t, and so I could only ask, “What are you ashamed of?”

Teese sighed, a sound I had taught him to make. “I spent too long meditating,” he finally said.

“Did you forget to eat?”

“Hm. I suppose I did, but I don’t think that’s why—You shouldn’t have had to drag me out of the closet.”

“I think we’re doing something a little beyond gay here,” I quipped, then wished I hadn’t as gray puzzlement dusted itself over the shame blotching his skin. “Never mind, bad joke. But if it wasn’t hunger, why did you pass out, or whatever that was? Teese, are you sick?”

“No, no,” he said. “You don’t need to worry, Ami. I’m fine.” He sighed again. “It was—I was—I just don’t know how to explain it.”

“Try,” I urged him. Partly because I was worried and scared, and partly because, as we talked, the shame was slowly fading from his skin, supplanted by the dark-orange fractal trees Teese sported whenever he was thinking hard.

“Well,” he said. “I was… I was looking at the walls and I got… too much blue.”

“Too much blue,” I said.

“Yes,” he said. “I thought, I am meditating, I am going deeper and deeper into the blue. And then it was too much.”

That was unusually unarticulate, for Teese. He was usually better at expressing himself in English than I was. His skin was clearing and dulling to a muddy grey.

This one I knew well. “You look tired,” I said. “Let’s get you into bed.”

“Yes,” he said. He started to haul himself down the hallway toward the bedroom, not even bothering to stand.

I covered my mouth with my hand. Teese usually stood himself up on four of his six limbs. The velvety undersides of his limbs gripped together along most of their length and the tips acted like feet, scooting him along the floor. It made him about as tall as a person, a head above the average man, and left him two limbs free to act like arms. Of course I’d known that the posture was for our benefit, that Teese’s people didn’t spend all their time standing like that on their own ship. But he’d always kept it up, even in our apartment, with just the two of us. And now—now he was just hauling himself along the floor, one tired limb at a time.

“I’ll get you some water,” I said, and fled to the kitchen.

When I came into the bedroom, Teese was in bed, head on the pillow, eyes almost closed. I fumbled for a limb-tip, pressed the damp glass into it.

“Thank you,” he said. “Ami, will you stay?”

His skin was still gray with exhaustion. “Yes,” I said. “Teese—”

He opened one eye fully, fixed its heart-shaped pupil on me. “Ami?”

I’d been about to scold him, to tell him I had had no one to call, no way of knowing whether he was near death and no one to ask. But even in the dimness of our bedroom, I could see the gray mottling his skin. If I’d been a hexie, I would have felt exhausted just looking at him.

“I was worried,” I said instead. I slid into bed with him and curled up against his arm. I think he was asleep before I’d pulled the covers up. But I lay awake a long time, watching the light from car headlights slide across the ceiling, mottling it bright and dark.

* * *

Teese was my first live-in boyfriend, although that feels strange and wrong to say. Teese was a friend, more than a friend, but there was no way to think of him as a boy or a man. I can’t say that he was my first love. He didn’t move in because I loved him. He moved in because the sex was great and because he couldn’t rent an apartment to save his life. The morning after our first night together, I learned that Teese had been couch-surfing his way up the Atlantic seaboard. Then I went to work at the gas station, and when I came home we had fantastic sex, then ordered pizza and ate it together messily on the couch and fell into bed, and the next day was pretty much the same, and slowly it dawned on both of us that Teese was staying.

* * *

I couldn’t really afford the rent on the apartment by myself. I needed a roommate, someone willing to pay me to sleep in the living room of my one-bedroom hole-in-the-wall slice of crumbling neo-Gothic shitpile. Instead I got Teese.

“I can pay you,” Teese said. “I receive high pay and long leaves in exchange for my long watches. The trouble is that local landlords do not want a hexie and I have not found a hotel who will take my currency.”

From somewhere he produced a thin, shiny rectangle. “Here,” he said. “This is rhodium. I haven’t checked the price for a while, but it should be worth at least a month’s rent.”

I took it gingerly. It was about the size of half a Thin Mint, maybe a little thicker. There were odd markings on it, presumably spelling out “YES THIS IS REALLY RHODIUM” in Teese’s language.

“Teese,” I said, “I have no idea what to do with this.”

“You could sell it?”

“Who could I sell it to? Do you seriously think I can go to Downtown Crossing with this and find some guy in Jewelers Exchange who’ll say ‘Oh yeah, this is alien rhodium, we get this all the time’ and give me a stack of cash?”

Teese waved a tentacle that was freckling olive-green with exasperation. “Well, at least you believe me. All the hotels I tried just pushed it back at me and said they couldn’t take it.”

“All the hotels—wait, did you try taking it to a bank?”

The olive-green freckles spread. “Of course I did. They told me they required a jewelers’ assay. The jewelers told me they required payment in advance for the assay. And of course they cannot take payment in this possibly worthless metal.”

I sighed. “Well, maybe you should try again next month. Sooner or later one of your shipmates is going to get a paycheck cashed, and then all the rich people will be buzzing about the dank alien rhodium and scheming to get it out of you as fast as they can.” I pushed the rhodium tablet back into Teese’s tentacle.

He made the tablet disappear again. “Maybe you’re right,” he said. “But in the meantime, Ami, how will you pay for the rent? Shall we get a roommate?”

“Um,” I said. “I don’t know if that’s a good idea with you already staying here.”

“It would be crowded,” he said, stippling with agreement.

“Right,” I said. “Crowded. I’ll see if I can pick up any extra shifts at work, and if I can’t I’ll short my student loan payment this month.” Again.

* * *

I had to take two buses and a train to get to the Citgo where I worked. Metro Boston, where none of the workers at the gas stations can actually afford to keep a car. But, unlike driving, the bus gives plenty of time to watch the scenery. A sign in a restaurant window caught my eye. “WE SERVE OCTOPUS!!!!” Not calamari, octopus. I didn’t know octopus had a culinary following, I thought. And then, Wait, are they trying to say they’d serve Teese? Hexies can eat there? But then another sign flashed by. Tiny baby octopus marinated in a thick brown gravy, with thickly markered letters shouting “THIS IS HOW WE LIKE ‘EM!” “This” was underlined six times. And another: “I LIKE MINE CHOPPED AND FRIED.” And another: “OCTOPUS IS BEST DEADED AND BREADED $16.95!!!” I shifted in my seat. I was starting to feel uneasy. Were people really eating octopus to express their resentment at the hexies’ presence? It was stupid, a stupid thing to wonder and an even stupider thing to do; so stupid that I could just about see people doing it.

I shifted in my seat again. How many people on the bus with me felt the same way as the sign-writers? How many were chopping up octopus at home and calling it Hexie Surprise?

And what would they do to me if they knew I was fucking one every night?

* * *

“Ami,” Teese asked, “what are you feeling?”

I opened my eyes. “Umm,” I said. “Sleepy?”

He shifted in bed beside me, propped himself up on one limb so he could look down at me in the dimness. “Besides that. Are you happy? Are you sad? Are you annoyed? It is difficult for me to tell.”

I shifted too. “Well, now I’m feeling awkward,” I said. “I think everyone has trouble telling how someone else is feeling sometimes, Teese. Especially in the dark, you know?”

“For my people,” Teese said—he never called them ‘hexies’—”it’s harder to see feelings in the dark too. But it’s not that dark. You can see my skin, and I can see your body and your face.”

“It’s probably just harder for you than for, you know, other humans,” I said. “Like, I had to learn that when you go a certain kind of pattern of olive green, you’re getting really annoyed. And it doesn’t hit me in the gut the way it does when I see a person with a mad face. It’s like I have a, a secret decoder ring in my head that I have to check. I turn the dial to ‘olive green squigglies’ and I see Oh, Teese is feeling frustrated or annoyed. And then I can start to have my own emotions about that.”

“Hit you in the gut,” Teese said thoughtfully. “When you see someone angry, Ami, you feel their anger too?”

“Not exactly,” I said. “I might feel scared, actually, especially if they’re mad at me and they’re bigger and stronger.”

Teese lay back down. “That is very different,” he said. “In my people, if I see someone who is angry, I feel their anger immediately. And they know I feel it because they see it reflected on my skin.”

“Yeah, I know,” I said. “Do you ever get a surprise that way? Like, you didn’t realize you were angry until you look at the guy next to you and see that he’s mad too?”

I felt Teese shift to look at me with both eyes. “Why wouldn’t I know I was angry?”

“Or sad, or whatever.”

“But why wouldn’t I know I was sad? Ami, all my life I have seen my feelings on myself and on everyone around me. I would have to be—damaged not to know my own feelings by now.” He paused. “Probably there are people who are damaged like this, children who are born blind and have to be told their feelings and everyone else’s. But you won’t meet them on a starship’s crew.”

Is that how you think of me—damaged? I bit my tongue, held in the words. But I felt my body moving away from Teese slightly.

After a pause, Teese spoke again. “I feel blind with you, Ami,” he said. “I see your face change and I don’t know what it means. Or your voice, or your body. I am like that blind child who can’t read skins, when I’m with you.”

“Welcome to the human race,” I said.

* * *

After he moved the towels back into the closet, Teese asked if he could use my computer while I was at work. I told him I was shocked that he hadn’t been using it already, and showed him how to log in and how to connect to the wi-fi and how to google. He tapped the keyboard delicately with the very tips of two tentacles, like a two-fingered typist, while I got ready for work. When I left, he was browsing Reddit at the kitchen table.

When I got home after work, Teese was still in the kitchen. “I found a way for us to make money,” he called.

I stuffed my coat in the closet and headed into the kitchen. “Really? Whatcha got?”

“Look at this,” he said, pushing my laptop toward me.

“Oh, ewww,” I said. A naked woman rubbed a dead octopus over her genitals. “Are you kidding me?”

“I know, I know, just look,” he said, pulling up another page. A woman was having sex, improbably, with a horse. And then another: a man and a—pile of balloons?

I was getting a nasty feeling about Teese’s idea. “What the hell?” I asked.

“I know! There are all kinds of pictures of people putting their genitals in things and on things. All kinds of things! Animals, people, food, machines! And they get money for this! Is this news to you? It was news to me.”

I made a face. “Teese, I am not going to put an octopus on my twat for money. That’s…. ” Words failed me.

“No no, of course not,” he said quickly. “I would not ask you to do that, Ami. But there is one thing I did not see in all my searches. I found all kinds of people having sex with every kind of thing, but never with…” he paused dramatically “… one of my people!”

His big eyes focused on me expectantly. Yes, my boyfriend was suggesting that we camwhore ourselves for rent.

“Oh, Teese,” I said helplessly. “Setting aside the fact that I’d probably be lynched, that’s… that’s…” I sighed. How was I going to explain porn to someone from another world? “Let’s get delivery. That’s a long conversation.”

* * *

I got home the next night to find him swiping tentacles broadly across the keyboard and staring at a text editor. “I installed Python,” he said. “I hope that is all right.”

I stood staring at his keyboard technique. “Sure,” I said, “just ask first next time, and… how are you doing that?”

“Doing what?” he asked, covering the keyboard with two arms. Lines of text appeared on the screen as if by magic.

“Typing?” I said. “You are typing, right?” If I looked very closely, I could just see the top of his arms twitch.

“Oh! I found that this is the easiest way to operate your keyboard, Ami. A little focused pressure on each key works just as well as striking. It took a bit of practice, but it’s not too different from the interfaces on our ship.”

“It just looks like you’re hugging the computer and it’s writing text for you,” I said. “What’re you writing, anyway?” I peered over his shoulder. It looked like free verse in English-laced gibberish.

“Python!” said Teese enthusiastically. “I told you, I installed one of your programming languages. It is not terribly different from your spoken language. I am writing a program in Python. Do you know this language too?”

“Um,” I said. My nearest approach to programming had been customizing my Facebook settings. “No, can’t say I do.”

Teese lifted his arms off the keyboard and started telling me about his program. I tuned out and watched his skin. Watery gray patterns rippled enchantingly across his arms as he gestured. It wasn’t quite like anything I’d seen before, but it was familiar, reminiscent of his skin when we were having a particularly intense conversation.

“And then —” Teese interrupted himself abruptly. “But you are not interested in this, Ami?” He peered up at me.

“I’m not a programmer, Teese,” I said. “But go on. I can tell you really had fun working on this.”

Teese’s skin pinked and dimpled, his way of smiling. “I did indeed. Here, look at this.”

He hugged the keyboard again. The screen blanked, then broke out in cheesy red hearts. “I LOVE YOU AMI” scrolled over the pulsing hearts.

I burst out laughing. “Is this what you spent the day on, you nutball?” It was awful. I loved it.

Teese’s skin rippled with pinkish-brown giggles. “Anything for you!”

* * *

Teese kept up with his programming hobby. After the love note came bouncing hearts that filled the screen, blanked, and repeated. Then it was fractals, lacy whorls that spiraled chromatically across the small screen. Then seascapes where the shifting lines of ocean blended into deep blue sky.

I thought Teese was programming to kill time. I had no idea he had a goal in mind. Day after day, I came home to find that he’d built another seeming frivolity. His electronic compositions were getting bluer, though, tending toward the same pale teal he’d painted the closet.

I suppose that should’ve been the third warning sign; or maybe it was the fourth. I’ve lost count.

But I ignored it, like I’d ignored all the others, because every night when we made love Teese looked deep into my eyes and told me he couldn’t imagine life without me.

* * *

When I got home the next night, Teese was back at the kitchen table. “I found another way to make money!” he called to me.

I couldn’t help grimacing. “I think I liked it better when you met me at the door with sex,” I said.

“This is better, I promise,” said Teese. “I’m going to surprise you with it. Some of my crewmates have figured out the banking system and they are the ones who will pay me.”

“In rhodium?”

His skin rippled with brown giggles. “No Ami, no more rhodium! Cash! Wire transfers!”

I came to stand next to him. The screen really was filled with gibberish, as though someone had transliterated a foreign language into English and sprinkled it liberally with varicolored emoticons, often mid-word.

“This isn’t a program, right?” I asked. “Just checking.”

“Chatroom,” Teese said happily. “It is a non-sanctioned communication between members of my ship. There is a metals exchange in California where my crewmates have been able to exchange their pay at a reasonable rate. I have known about this, but I have no desire to go to California, actually —” he peeked up at me almost shyly “—I would much rather stay in Boston.”

“I’d kinda rather you stay here, too,” I said. “So are they going to exchange some of your rhodium for you? Like, you have a ship bank you can transfer it to them with, and then they transfer you back the US currency?”

He waved a tentacle. “Actually, shipboard regulations would make that complicated,” he said. “Private crew currency exchanges are not very encouraged. Otherwise I could already have done that. But now I have something to sell.”

“You do?” I said. “What is it?”

Teese pinked with pride. “I have created a program that my crewmates desire!”

“Really? What does it do?” I was really curious. I couldn’t imagine what Teese had cooked up on my old laptop that sophisticated space-faring hexies would pay cash for.

Teese stroked the keyboard. The screen went black, then slowly faded into a shifting, pale aquamarine. It was a seascape, an abstract, a fractal, all of these and none of these at once. Barely felt lines radiated from the center, branched, shifted, dissolved. Dozens of fractal forms shimmered and danced in the background, shifting and changing. It reminded me of waves rippling the ocean, of sand grains roiled by wind, of the patterns on hexie skin.

It was mesmerizing. It was beautiful, it was somehow alien, and something about it was hauntingly, naggingly familiar.

After a few minutes, the screen blanked. “It has a timeout,” Teese said quietly. “So that I do not become—lost.”

I sat back. “It’s gorgeous, Teese,” I said quietly. “Are you an artist? Back home, I mean.”

“No, no,” he said. “I never had any interest in this. But now I have inspiration, Ami.”

“I can see why your people would pay for this, especially if they’re all as into blue-green as you are,” I said. “But wait, didn’t you tell me that your people would find so much blue tacky? Like that all-purple painting I had once?”

Thoughtful orange fractals rippled Teese’s skin. “Actually, it is kind of tacky,” he said. “But it is more than that. Ami, you can have no idea how interesting, how appealing and stimulating this is for one of us. When I look at this, I feel—things I cannot feel without it. That’s why I put in the timeout,” he added pragmatically.

Art has always prompted strong feelings in people, so I assumed that’s what Teese was talking about. I thought it was a little weird for Teese to talk about his own art like that. But Teese clearly hadn’t been exaggerating, because the money started rolling in. He’d never managed to get a US bank account, so the money went into my account. Suddenly, rent was no problem. I paid the rent, made up all the student loan payments I’d shorted, and still we had more money coming in each week than I made in a month at the Citgo. I thought about quitting my job, but didn’t.

Teese wanted to take me out to dinner, to shows, to operas that neither of us had the slightest interest in. I demurred. We hadn’t been out together since he’d come home with me. At first there had been a steady flow of invites to parties, ostensibly for me but always appended with, “Oh, and be sure to bring that hexie who’s staying with you.” But we’d been too wrapped up in each other to go out, and the invitations had slowly dried up. Now we had piles of money and nowhere to go. I wouldn’t have minded taking Teese to a few house parties, but Teese wasn’t interested. “I’ve met lots of humans,” he told me. “Now I have met you. Meeting more humans will just be—disappointing, I think. But I want to take you out, Ami.”

“I don’t really need to be taken out,” I told him. “I’m pretty low maintenance.” And I don’t want to be lynched, I added silently. Teese might have met lots of humans, but they’d mostly been liberal, east-coast, college-educated twentysomethings at house parties. As far as I knew, he’d never even seen the “WE SERVE OCTOPUS” signs I passed on my way to the Citgo. And I wanted to keep it that way.

We compromised on a museum date in the afternoon. Boston is dripping with museums. We went to the ICA and looked at all the blue things.

“I think your computer art is better,” I murmured to him, just to see him pink.

He rippled brown with laughter instead. “I did have unique inspiration,” he said cryptically.

“Being inspired to pay the rent is far from unique,” I shot back. He just laughed in return.

That might have been the fifth warning sign; or maybe I’m just paranoid in retrospect.

* * *

The next day, I had a double shift at the gas station. I came home to a dark, silent apartment.

“Teese?” I called out, groping for the light switch. Maybe he’d gone out?

Something moved in the darkness. Startled, I dropped my coat and hit my head on the door frame. “Ow! Shit!” My hand finally found the light and I snapped it on.

Teese was hunched in the corner of the room, skin soot-black. He’d been nearly invisible in the dark.

“Teese, what’s going on? Are you okay?” As I spoke, I noticed that the little duffle bag he’d brought with him when he moved in was sitting beside him.

“Ami,” he said quietly. “No. I am not okay. I have been recalled to my ship.”

I came in and closed the door behind me. “Why? What’s going on? Are the hex—are your people leaving?” I hadn’t heard anything on the news.

“No,” he said. “Not as far as I am aware. No, this is personal. My commander is displeased with my actions and has terminated my leave.”

“Your actions—Teese, what did you do?”

“It’s about my program,” he said. “And about selling my program to my shipmates. This has been ruled, ah, trafficking I believe is the word.”

“Trafficking? Like your program is a drug?”

“Exactly like that,” he said. “I told you that it has a strong effect on my people. It has been deemed an intoxicant.”

“Your art is a drug?” I slid down to the floor, back against the door. “Are you in trouble?”

He waved a tentacle. “Yes and no,” he said quietly. “If I report to the ship immediately, it will not be so bad for me. I should have left a few hours ago, I think. But I had to speak with you first.”

“I had a double shift,” I said inanely. “Wait. Wait. Are you coming back?”

“No,” he said softly. “I will not be allowed to come back. And I have more bad news to tell you.” He was still coal-black, but now his skin blotched red with shame as well. “The money has to go back. Everything my shipmates have paid for the program must be returned. Even though I made a gift of it to you. The ship’s bank will take it back, right out of your account.” His voice had faded to a whisper on the last.

“But we spent some of it,” I said. I’d go into overdraft.

“I know,” he said. “I—I will leave you the rhodium. Perhaps you will be able to exchange it soon.”

I stared at Teese. The red hexagons spun and spun on his coal-black skin. He focused his heart-shaped pupils on the floor.

“I know the red,” I said, “But what’s the black?”

He murmured, so softly I could barely hear him, “I am afraid.”

“You’re scared of what they’re going to do to you?”

“No. I’m afraid of how I will feel, not seeing you. I am afraid of how it will hurt me.”

“I could come with you,” I said suddenly. “It’s an interstellar ship, right? And you have years-long shifts watching over your frozen shipmates? You must have some provision for bringing your partners on there or you’d go crazy.”

Violent brown lightning flashed across his black-red skin. A bitter laugh, I realized. “Take you with me!” he said. “Ami, don’t you realize? How don’t you realize? You are the problem, Ami, you are the last human they would ever allow on the ship!”

I felt like he’d slapped me. “What? Why? How am I the problem?”

The shame-red bled away from black skin that crackled with jagged, bitter laughter. “How are you the problem!” he repeated. “You’d be a walking riot. My shipmates would fight each other to look into your eyes. They’d beat each other to death to be the one to make you come.”

“Make me come,” I said slowly. An awful light was dawning inside me. All the times Teese had said he loved to look into my eyes. My greenish-blue eyes. The strange familiarity of his program, as though I’d seen it somewhere before. His greenish-blue program that was, I realized now, the exact shade of my eyes. Just like the sunset that had so captivated him, and just like his “meditation closet.”

“The way your eyes change,” he said, “Ami, the way your eyes change when you come. The blood vessels, the tiny capillaries, they dilate.”

I saw it now. “Fractal patterns moving through them, like hexie skin,” I said. “And what you see, you feel.”

“And what I see in your eyes, I have never seen anywhere else.”

Teese’s romantic-sounding words came back to me. I have never felt before what I feel with you. He had meant it literally. His limbic system responded to something in my changing eyes with a new emotion, one that none of Teese’s people had ever felt before, while his skin struggled and failed to keep up, lapsing into static.

I sat with my back against the door and thought back over the past months. Teese had only said he loved me once, in a cheesy e-valentine. But he’d told me that he loved to stare into my eyes at least a dozen times. I’d naively thought that that meant the same thing.

“I was never your girlfriend,” I realized out loud, “I was your drug.”

“Please don’t say that,” he said. But I was pettily satisfied to see red shame-spots creeping back onto his black skin.

I stood up. “You’d better get back to your ship,” I said, moving away from the door. “Just tell me one thing. What did it feel like? What did you feel when you looked into my eyes?”

He was silent for a long moment. “What is the word,” he said finally, “for a color no one has ever seen? How could there be a word for it?”

“Was it a good feeling, at least?”

He closed his eyes. “It was like nothing I’ll ever feel again.”

He paused at the door, as if wondering whether to kiss me goodbye. I stared him down. He looked into my eyes one last time, and left.

* * *

After Teese left, I pocketed his rhodium and went for a walk. I wanted to hate Teese, but I couldn’t. He’d never lied to me. He’d been telling me exactly what he saw in me from the moment he’d first seen me. I just hadn’t heard.

And what if I’d been the one given the chance to feel a brand-new emotion, one never felt by anyone before? I probably would’ve taken it. Hell, I’d let an alien move in with me mostly for the orgasms. And if I’d loved that alien later—well, that wasn’t his fault either, not really.

I fingered the rhodium. Teese couldn’t get anyone to exchange it, but that might’ve had more to do with his tentacles than with the metal’s value. I still couldn’t see myself haggling over it at Jewelers Exchange, but I could probably pawn it for a few hundred to tide me over, and buy it back when I had the money to pay for an assay.

Because I did plan to have more money. Teese might be a terrific programmer, but he’d never learned to clear his browser history. It’d be easy to find the hexie message boards where Teese had sold his now-banned software. I didn’t need the software. I’d just aim a webcam at my eyes and the money would come flooding in.

I’d have dozens of hexies staring into my eyes, chromatophores fluttering. Maybe hundreds of hexies—who knew how many Teese had hooked on his program? Enough to worry his bosses. Enough, I realized, to enforce a ban on Teese if I made it a condition of my show.

It wouldn’t be porn, not in any human sense. Not as long as Teese wasn’t watching.

I couldn’t truly hate Teese. But I’m only human. And I couldn’t help thinking of Teese, sitting alone in his quarters, skin rippling with regret, while his shipmates watched my eyes as I came. And I felt —

Well. If I had been a hexie, my skin would have pinked and dimpled at the thought. But I’m human, so I had to make do with a smile.

* * *

Originally published in Writers of the Future, Volume 34

About the Author

About the Author

N. R. M. Roshak writes all manner of things, including (but not limited to) short fiction, kidlit, and non-fiction. Her short fiction has appeared in Flash Fiction Online, On Spec, Daily Science Fiction, Future Science Fiction Digest, and elsewhere, and was awarded a quarterly Writers of the Future prize. She studied philosophy and mathematics at Harvard; has written code and wrangled databases for dot-coms, Harvard, and a Fortune 500 company; and has blogged for a Fortune 500 company and written over 100 technical articles. She shares her Canadian home with a small family and a revolving menagerie of Things In Jars. You can find more of her work at http://nrmroshak.com, and follow her on Twitter at @nroshak.

The Starflighter from Starym

by Tamoha Sengupta

“On her back, the city disappeared, part of an ancient trick her ancestors mastered while building their world—in other worlds, their cities would not be visible unless Starym songs were heard.”

“On her back, the city disappeared, part of an ancient trick her ancestors mastered while building their world—in other worlds, their cities would not be visible unless Starym songs were heard.”

If legends of lost cities were true on Earth, some credit for these tales went to the whales that lived on the planet of Starym, situated outside the reaches of the Milky Way.

* * *

Mahi swam through the endless swirls of stars and planets, the universe expanding endlessly around her.

This was the first time she was carrying out the annual tradition of Starflight. Her mother had been the previous Starflighter, and her grandfather had been the first to carry out this noble task. She was proud to uphold family traditions in something this important.

A piece of her home was securely attached on her back. It was the part of the city she adored the most: six buildings set in a circle; the arch leading towards them decorated in two thin strands of Shimmer Moni—the rarest gems of the universe, the only existing ones of their kind.

She knew why she was chosen to protect the most precious part of the city—the part that the Arras would actually steal when they invaded Starym—she was the fastest swimmer and had the best ears.

“Remember our songs”, their leader had sung to her. “Keep your ears open. When the dangers pass, we’ll sing for you to come back home.”

Mahi had sung back her consent, and with the city on her back, swam up through the cyan skies of her world and into the outer darkness.

It would take her only three whale days to reach the nearest sun system. There was a planet there, with everlasting sapphire oceans like the ones back home, and that would be the best place to hide the city till the Arras left.

Mahi wondered if the Arras would stop attacking if they shared a bit of the Shimmer Monis with them, or whether they would increase the frequency of attacks if they realized that Starym whales indeed possessed the gems.

Either way, they couldn’t risk it—for the Arras wanted the gems for the decorations of their planet, and Staryms needed it. Only when the light reflecting off the strands of Shimmer Monis fell on the Starym eggs, did the eggs hatch.

Mahi’s eyes shone in the light of a billion stars as she swam. The survival of her species rested on her back. Literally.

* * *

When Mahi saw the blue world for the first time, it had curtains of green and red dancing over it, softly waving in the stillness of the skies.

The leader’s words swam in her head.

If you sees sky lights, dive into waters beneath it. Less chances of discovery there.

She followed the lights towards the oceans below, and she stopped for a moment in surprise—the waters really were as blue as those back home.

On her back, the city disappeared, part of an ancient trick her ancestors mastered while building their world—in other worlds, their cities would not be visible unless Starym songs were heard.

She crashed through the surface ice. Underneath, the world was cold and dark, and Mahi felt the first aches of loneliness rush through her.

She hoped that the Arras would leave quickly, but time passed differently in different planets, and she wondered how long it would be before she could go back home.

* * *

There were other singers in the waters, but they spoke in a different language. They swam past her, calling out to each other, nudging and playing in groups as they did so.

Mahi thought of her friends and the skies and the oceans where she swam, and she thought of Starym songs, similar and yet so different from the songs of these creatures.

Sometimes, she was afraid that she would forget her own language, and so she sang too, her voice muffled in the lonely blue.

No one answered her, but above her, the city came into existence, its Shimmer Monis glowing in the dark. It gave her hope that it was all real, that she was not really alone, that a part of her world was always with her.

She was careful to keep the songs short, to make sure that nobody saw the city.