Retrospective review: 'The Wolf Man'

It's October, and that means Halloween.

It's October, and that means Halloween.

To celebrate that fact, I'd like to offer a series of reviews on various werewolf movies.

Werewolves are the closest the worlds of furry and horror brush the closest to each other, though they may have more in common than they seem.

Both furry and horror deal with things of dual natures. Furry explores the line between what we mean when we say "human", and what we mean when we say "animal". The werewolf movie, more than any other sub-type of horror movie (or horror story), explores this same trope, and not just the difference between "wolf" and "man".

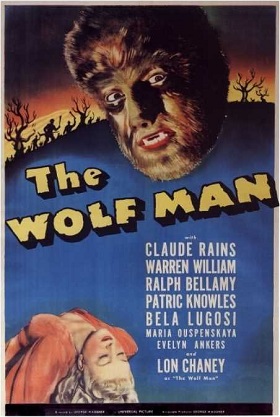

Our first stop in this tour of wolf-men is the obvious one, 1941's The Wolf Man, written by Curt Siodmak and starring Lon Chaney, Jr. as Lawrence "Larry" Talbot, a.k.a. the Wolf Man.

A monster's foundation

It can more or less accurately be said that, for all intents and purposes, The Wolf Man invented the werewolf as we know it today. Less accurately, because it was hardly the first werewolf story ever told. It's not even the first werewolf movie made by Universal Pictures. It was preceded by the inferior (but still worth seeking out if you're into this sort of thing) Werewolf of London. The Wolf Man set the rules that other movies and stories in other media would either follow, or consciously break from. If a character in a future werewolf movie says something about their werewolf not being "like one from the movies", they're really talking about one movie, and it's this one. Like Dracula for vampires or Night of the Living Dead for zombies, The Wolf Man is built upon past werewolf lore, and later iterations would build upon them. But it's still a useful guidebook for future werewolf iterations.

Well, what are the rules?

- A werewolf is a human who turns into a wolf, or wolf-like creature, at the full moon.

- They are only vulnerable to silver.

- If a werewolf bites another person, and that person survives the encounter, they too are now a werewolf.

- A werewolf in human form is marked by a pentagram, usually where the original bite occurred, and he can tell who will be his next victim if he can see a pentagram in their palm. If this one doesn't sound familiar, this rule is one that is the most likely rule to be passed over by future werewolf stories.

This movie makes sure we get the silver, pentagram, and bite things, but it's actually vague about the moon thing. There is no actual shot of the moon in the entire movie, something more unheard of in later werewolf movies (even if they ignore the "full moon" rule). The only real hint we get that the moon has anything to do with what's going on is the famous verse:

Even a man who is pure in heart and says his prayers by night, may become a wolf when the wolfbane blooms, and the autumn moon is bright.

Note that, in a pedantic reading, you're completely safe from werewolves during the winter, spring, and summer. In fact, you could argue that the wolfbane blooming is more important. We at least get a scene involving coming across the flower in bloom, where the little poem is quoted for the third and final time ("So you know that one too?" quips our protagonist, Talbot).

Duality

But enough about the rules, what are the themes of the movie? The movie straight up admits that "lycanthropy" can be seen as a symbol of the "dual nature" of man. Dualities pop up frequently during the movie. On one hand, Larry Talbot is a mechanic, used to fixing machines; on the other paw, he's found himself in world full of gypsy fortune tellers and ancient curses. His father (played by Claude Rains) is on the side of science, fully insisting that this "werewolf nonsense" is all in Larry's head. He notes that his son just had a bad accident involving an escaped wolf and an unfortunate gypsy, and he feels guilty that he was unable to save a local village girl and that he apparently beat the gypsy to death in the confusion. Larry's having a nervous breakdown, not becoming a werewolf.

This theme is where the main horror, as well as the main tragedy, of the movie lies. Yes, I suppose the horror of being hunted down by a werewolf is scary, never mind the existential anxiety of its existence. But the real point is that the Talbots have their completely rational worldview destroyed by the existence of this creature. There's an argument in horror about which is scarier: a supernatural or natural danger. On one hand, some argue a supernatural threat is less scary because it doesn't exist. There are no werewolves, so why should we be afraid of werewolves? The other view is that the supernatural is scarier because, unlike, say, a crazed serial killer, which may exist in the real world, a supernatural threat, if it did exist, would change the entire world, revealing that the victim, even if they survive, was blissfully unaware of entire realms of danger. In fact, the last lines of the movie are a pair of characters trying to explain away what just happened right in front of them.

The setting is very interesting, because it is maddeningly vague as to where and when the movie is supposed to take place. Characters drive around in cars, but they also ride around in horse drawn carts. Characters have telescopes installed in their homes, look up things in encyclopedias and discuss psychology, but there are still gypsy caravans roaming the countryside, and they are able to rattle off couplets about werewolves fairly easily. Castle Talbot has all the modern conveniences, but it's still Castle Talbot with it's strange grounds, dead trees, marshy earth, and ever present fog. The movie is both unashamedly Gothic and very modern.

Perhaps an interesting contrast between the science and superstition theme is a clash between superstition and religion. The movie very clearly has characters compare and contrast religion and superstition and proclaim they are not the same thing. One under-valued scene from the movie features Larry beginning to attend church one Sunday morning, only to find himself completely unable to bring himself to cross the threshold. It's a strangely creepy scene, and also tragic, as various churchgoers turn around to look at this strange newcomer before finally his own father turns around to see what's going on.

Defining Roles

Let's face it, the movie works better as a tragedy than horror today. It's just not that scary anymore. But there is still a lot of sadness in the movie, thanks to a trio of central performances. The first is, of course, Lon Chaney, Jr. Chaney is not, in point of fact, a very good actor, but in the right role, he's perfect. Today, he's basically known for two roles: this (the Wolf Man is the only "Universal monster" played by one actor in all subsequent sequels) and the role of Lenny in Of Mice and Men, another tragic character often described as a "gentle giant", though that's not entirely correct. He wants to be gentle; the fact that he really, really isn't is the tragedy. Chaney is very good at this kind of tragic role where his continued existence is a danger to all around him, but it's not his fault.

Claude Rains is a much better actor, still fondly remembered for a variety of roles even today, including the lovable comic rogue Captain Renault in Casablanca ("I’m shocked, shocked to find that gambling is going on here!") as well as the title role in the more comic Universal horror picture, The Invisible Man. Here, seeing as how we're talking about tragedy, we don't get that funny side, but it should be pointed out, as written, Rains' character could come off as very unlikable. Rains keeps you on the character's side, however.

Finally, Maria Ouspenskaya plays Maleva, the old gypsy woman who was the mother of the original werewolf in the movie, and is basically the only character who knows exactly what's going on the entire time. Despite the fact that she knows full well that Larry killed her son, and that he's now a dangerous wolf monster, she is an untiring ally of the cursed man. It's overshadowed by the more repeated werewolf couplet, but her own repeated poem (beginning "The way you walked was thorny, through no fault of your own") is much closer to the movie's thematic heart.

So, this was The Wolf Man, the foundation of what would become it's own subgenre of horror: the werewolf movie. Later films would build off this foundation, of course. However we will cover those another day.

About the author

2cross2affliction (Brendan Kachel) — read stories — contact (login required)a red fox

New teeth. That's weird.

Comments

“Werewolves are the closest the worlds of furry and horror brush the closest to each other.”

I dunno. What about the Cthulhu plush doll? It’s fuzzy. It’s bright green. It’s dressed like Santa or a clown or something supposedly cute.

https://www.newegg.com/Product/Product.aspx?Item=9SIA0192D54743&ignorebbr=1&nm_m...

Or killer rabbits? They’re pretty horrifying.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=m0DKTM41r1s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XcxKIJTb3Hg

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A6-YPiqOh_w

Fred Patten

I still remember my introduction to the tikbalang; a demonic, fire-breathing, fanged horse, either four-legged or anthropomorphized onto two legs.

It was around the 1980s when I met with comic-book artist Alfredo Alcala, who had come to the U.S. from the Philippines to draw horror comic books for DC. Besides showing me his DC work, he showed me several horror comics he had drawn in the Philippines. I was fascinated by the traditional Filipino monsters, especially the tikbalang; a glowing-eyed horse-monster; either a steed ridden by a worse monster, or a two-legged monster by itself. I told Alcala that they were much more imaginative than the standard vampire, werewolf, and Frankenstein's monster, and he should work them into his American comic books. He said that he'd already tried, and had been ordered by his American editors to forget them and use only the traditional monster-movie Big Three.

It’s too bad there aren’t any horror movies with tikbalangs.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tikbalang

Fred Patten

Huh, the Wikipedia article says it stems from Hinduism, but I always assumed it one of the idiosyncrasies of Filipino Catholicism because I'd always learned it as essentially the Devil leading people astray/into confusion/etc, literally

I had assumed that it was a result of the Spanish Conquistadores introducing horses into the Philippines during the 16th century. Probably the Spanish Catholic priests did all they could to connect tikbalangs and any other pre-Christian mythological creatures with devil worship, which helped turn them into creatures of evil.

Fred Patten

>Doing 40s horror but not doing Cat People

Catpeople never became it's own subgenre I can write about for a month, though.

I agree about the tragedy part. This film isn't going to scare anyone but it still manages to be a great piece of gothic fantasy.

I also like how you brought up the significance of the wolf bane. It's an underutilized trope and I didn't even notice that it was only during the autumn until you brought it up.

Interesting how you brought up the fact that the werewolf exists between the furry and horror worlds. It reminded me of Francis Dolarhyde, another very likable character who shares many similarities.

BTW someone brought up Cat People. The movie has great cinematography and mood, but I never understood why people praised it so much. It dealt with LGBT subtext, and I understand that would be pretty risky for back in the day, but that hardly makes for the seminal film of the 40s. I mean it's literally number one on someone's list I randomly selected: http://www.imdb.com/list/ls003691624/

Don't get me wrong, it's a great film, just not as great as Phantom of The Opera or The Wolf Man.

The 1943 Phantom of the Opera fucking sucked, and it was based off a book for which there was already a film adaptation anyway, so didn't get credit for being groundbreaking anyway.

Maybe it wasn't that great back then, but it still beats any horror film you see nowadays. I mean, when something like Get Out is considered groundbreaking you know you're in trouble.

OH, YOU HAD TO RUIN IT.

An intriguing detail is that the French word for werewolf, loup-garou, translates literally as "wolf-shapeshifter". That implies that there are other shapeshifters.

But I've never heard of a renard-garou, a lapin-garou, a chat-garou, or any other kind of garou in French mythology. Were there any? Loup-garou goes back to Medieval French. Were there any other garous several hundred years ago that have been forgotten?

Fred Patten

Post new comment