Review: 'Watchers' by Dean Koontz

Dean Koontz first came to the public’s attention in the early 1970s. He was originally considered a science-fiction author (his 1975 far-future Nightmare Journey contains talking evolved descendents of animals), but he soon established a reputation as one of the leading authors of horror/suspense fiction with s-f, fantasy, or supernatural elements.

Dean Koontz first came to the public’s attention in the early 1970s. He was originally considered a science-fiction author (his 1975 far-future Nightmare Journey contains talking evolved descendents of animals), but he soon established a reputation as one of the leading authors of horror/suspense fiction with s-f, fantasy, or supernatural elements.

Watchers, his most popular novel, straddles the border between science-fiction and “realistic” suspense fiction involving genetic engineering. In a detailed analysis in Critical Companions to Popular Contemporary Writers (1996), Joan G. Kotker argues that it is a successful combination of science-fiction, suspense, a technothriller, a love story, a police procedural, gangster fiction and:

… overriding all of this, an inspiring dog story whose suspense is based on a series of threats to a very special dog.

NYC, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, February 1987, hardcover $17.95 (352 pages).

The protagonist of Watchers, Travis Cornell, is introduced as a 36-year-old loner who is going hiking in the hills of Southern California with a gun, mostly to protect himself against rattlesnakes, but maybe to commit suicide. He has lost any will to live. His family and friends are all dead. As a member of the Special Forces in the military, he was the only survivor of his team.

He has come to think of himself as a jinx; anybody whom he cares for dies.

As Travis was about to step out of the sun and continue, a dog burst from the dry brush on his right and ran straight to him, panting and chuffing. It was a golden retriever, pure of breed by the look of it. A male. He figured it was little more than a year old, for though it had attained the better part of its full growth, it retained some of the sprightliness of a puppy. Its thick coat was damp, dirty, tangled, snarled, full of burrs and broken bits of weeds and leaves. It stopped in front of him, sat, cocked its head, and looked up at him with an undeniably friendly expression. (p. 11)

The dog appears friendly, but it does everything but attack to keep Travis from continuing down a deer trail into the forest. Travis eventually realizes that the dog is trying to protect him from some unknown menace in the forest. The first scene of suspense follows as Travis slowly retreats with the unseen thing following him and the dog protecting him.

The unknown adversary’s raspy breathing was so creepy – whether because of the echo effect of the forest and canyon, or because it was just creepy to begin with – that Travis quickly took off his backpack, unsnapped the flap, and withdrew the loaded .38.

The dog stared at the gun. Travis had the weird feeling that the animal knew what the revolver was – and approved of the weapon. (p. 16)

As they retreat, the novel cuts to Vincent Nasco, a hired killer who is carrying out a hit.

Vince had been told that the doctor’s body must not be discovered until tomorrow. He did not know why the timing was important, but he prided himself on doing flawless work. Therefore, he returned to the laundry room, put the metal cart where it belonged, and looked around for signs of violence. Satisfied, he closed the door on the yellow and white room, and locked it with Weatherby’s keys. (p. 19)

The beginning of Watchers alternates several apparently unconnected scenes with those of Travis and the dog. Travis almost immediately realizes that the dog possesses human-level intelligence.

The timing, for God’s sake, had been uncanny. Two seconds after Travis had referred to the chocolate, the dog had gone for it.

“Did you understand what I said?” Travis asked, feeling foolish for suspecting a dog of possessing language skills. Nevertheless, he repeated the question. “Did you? Did you understand?”

Reluctantly, the retriever raised its gaze from the last of the candy. Their eyes met. Again Travis sensed that something uncanny was happening; he shivered not unpleasantly, as before.

He hesitated, cleared his throat. “Uh … would it be all right with you if I had the last piece of chocolate?” (p. 23)

Dying of curiosity, Travis keeps the dog. A new digression introduces Nora Devon, a paranoid woman as soul-dead as Travis was. She is terrified of her TV repairman, with good reason as it turns out. For the next few dozen pages, Koontz switches between scenes of Travis conducting intelligence tests on the dog, whom he names Einstein; Nora Devon being toyed with by the sexual predator, Vince Nasco being asked by his anonymous employer to murder more people, and the unseen menace killing people. After killing three doctors in a row, Nasco performs the unpardonable sin of torturing his final victim into telling him what connection the doctors had. They all worked at Banodyne Laboratories on a top secret project to increase animals’ intelligence – a research laboratory from which two experimental animals have just escaped.

Koontz draws Travis’ and Nora’s stories together, with Einstein acting as a canine chaperone/Cupid to develop a romance between them. But Nasco has decided that the escaped dog is worth a fortune to him, if he can find it. The novel also starts to play up the savage slaughters that the other escaped animal, called The Outsider, is committing around Southern California. Two lawmen, Lemuel Johnson of the National Security Agency and Sheriff Walt Gaines, investigate as friendly rivals; Johnson to recapture The Outsider and suppress all knowledge of it, and Gaines to catch whatever is killing people and animals in his jurisdiction and learn what the NSA is hiding.

So: Travis and Nora slowly fall in love, with Einstein’s approval. They do not know that Nasco is looking for Einstein to sell to the highest bidder, and that the killer plans to leave no human witnesses behind. Nasco’s anonymous hirers, presumably Soviet agents out to destroy the U.S. government’s research project, will want to kill Einstein and also his new human friends if they learn about them. The Outsider, a bioengineered killing animal derived from a baboon, has a telepathic affinity to Einstein and is searching to slaughter him and anyone with him. Lem Johnson, the only sympathetic antagonist, is duty-bound to return Einstein to the government research labs if he finds him, and do whatever the government does to civilians who find out too much about top secret projects. Once Einstein, Travis, and Nora figure out how to genuinely communicate with each other, and the dog tells them his secret, Travis and Nora vow to keep anyone from taking Einstein away from them.

What makes Watchers of interest to anthropomorphic fans, and of more interest than the average anthropomorphic novel, is, of course, Einstein. He is not just a human mind in a doggy body. He is an intelligent canine with a canine’s instincts. First they figure out a code of wagging his tail for yes and barking for no; then Nora teaches him to read.

Einstein was on the floor, on his belly, reading a novel. Since graduating with startling swiftness from picture books to children’s literature like The Wind in the Willows, he had been reading eight and ten hours a day, every day. He couldn’t get enough books. He’d become a prose junkie. Ten days ago, when the dog’s obsession with reading had finally outstripped Nora’s patience for holding books and turning pages, they had tried to puzzle out an arrangement that would make it possible for Einstein to keep a volume open in front of him and turn the pages himself. At a hospital-supply company, they had found a device designed for patients who had the use of neither arms nor legs. It was a metal stand onto which the boards of the book were clamped; electrically powered mechanical arms, controlled by three push buttons, turned the pages and held them in place. A quadriplegic could operate it with a stylus held in his teeth; Einstein used his nose. The dog seemed immensely pleased by the arrangement. Now, he whimpered softly about something he had just read, pushed one of the buttons, and turned another page. (p. 199)

Finally, Travis gets a Scrabble game so Einstein can spell out words, a letter at a time, with the tiles:

Then he stopped nuzzling Nora and spelled DARK LEMUEL.

“Dark?” Travis said. “By ‘dark’ you mean Johnson is … evil?”

NO. DARK.

Nora restacked the letters and said, “Dangerous?”

Einstein snorted at her, then at Travis, as if to say they were sometimes unbearably thickheaded. NO, DARK.

For a moment they sat in silence, thinking, and at last Travis said, “Black! You mean Lemuel Johnson is a black man.”

Einstein chuffed softly, shook his head up and down, swept his tail back and forth on the bedspread. He indicated nineteen letters, his longest answer: THERES HOPE FOR YOU YET. (pgs. 246-247)

All of the above is in Part One of the novel. In Part Two, the three go on the offensive against their pursuers. Travis’ training as a Delta Force commando is crucial against both Nasco and The Outsider, but how can they fight the whole NSA?

They elaborate upon the one Scrabble game, and upon human-canine communication, until Einstein is able and comfortable having long conversations with them.

As Einstein busily pumped pedals and clicked tiles against one another, Travis carried his beer and the dog’s water dish out to the front porch, where they would sit and wait for Nora. By the time he came back, Einstein had finished forming a message.

COULD I HAVE SOME HAMBURGER? OR THREE WEENIES?

Travis said, “I’m going to have lunch with Nora when she gets home. Don’t you want to wait and eat with us?”

The retriever licked his chops and thought for a moment. Then he studied the letters he had already used, pushed some of them aside, and reused the rest along with a K and a T and an apostrophe that he had to release from the Lucite tubes.

OK. BUT I’M STARVED. (p. 257)

Koontz is a virtuoso at playing the reader’s emotions, making alternately Travis, Nora, Einstein or one of their very few human friends seem in deadly danger. Even though Einstein is the only intelligent animal in the novel (except for probably the psychotic Outsider), Koontz makes him so charismatic that Watchers is a thriller that every anthro fan just has to read.

A new three-page Afterword added to the paperback fortieth printing in January 2003 confirmed that, at that time, his readers still considered it his best novel and wanted a sequel.

I will smile, promise to think about it, […] and explain that I don’t believe in writing a sequel to a book unless I can be sure it will be at least the equal of the original.

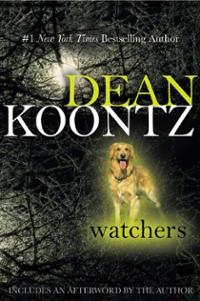

Putnam’s was responsible for the original cover by Don Brautigam, which is a generic horror/suspense painting that does not do the story justice. The best cover has been the anonymous one for the May 2008 Berkeley Books paperback that shows Einstein.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

As Einstein busily pumped pedals and clicked tiles against one another, Travis carried his beer and the dog’s water dish out to the front porch, where they would sit and wait for Nora. By the time he came back, Einstein had finished forming a message.

As Einstein busily pumped pedals and clicked tiles against one another, Travis carried his beer and the dog’s water dish out to the front porch, where they would sit and wait for Nora. By the time he came back, Einstein had finished forming a message.

Comments

I can confirm that Watchers was still Koontz's most loved book by fans up to at least 2008; I was getting recommendations as a horror fan up by people unaware I might be interested in a talking dog story until at least then.

Here is a better picture of Paul Lehr's cover painting for Koontz's "Nightmare Journey": http://www.isfdb.org/cgi-bin/title.cgi?883433

Fred Patten

It's great to see some love and exposure for "Watchers." I read the book in my teens, and it contributed greatly to my personal 'furry awakening.'

In a single read, "Watchers" showed me that intelligent animals have a place in adult fiction, and that such content held great appeal for me. (I was very disappointed when the next Koontz novel I dove into did not feature any similar animal protagonists.)

Koontz has written good anthropomorphic children's fantasy with "Oddkins: A Fable For All Ages" (October 1988), about the fight between a Good Toymaker and an Evil Toymaker through their live plush toys; Amos Bear, Skippy Rabbit, Patch Cat, Jack Weasel, and others. But no more anthropomorphic adult fiction. The Hollywood horror movie adaptations of "Watchers" have all been disappointing, too.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oddkins:_A_Fable_for_All_Ages

Fred Patten

Thanks a lot! ^^ I should check that out, along with "Nightmare Journey."

Fred: I have a feeling that you of anyone has probably read both of these (I haven't read either as of yet, but I've read ABOUT both of them). Anyway, can you compare/contrast this book with Sirius by Olaf Stapleton?

Yes, I read "Sirius" several times -- it's also very good -- and reviewed it in 2008. Both are about bioengineered heroic dogs, and convincingly describe an intelligent canine, rather than a human mind in a dog's body. "Watchers" ends happily, while "Sirius" ends tragically. It seemed to me no coincidence that in "Watchers", Einstein's intelligence is hidden from the public, while in "Sirius", it becomes public knowledge. "Watchers" is very late 20th-century American in both setting and writing, and "Sirius" is very conservatively mid-20th-century British, but they seem similar in their depiction of what public reaction to a dog with human-level intelligence would be.

http://anthrozine.com/revw/rvw.patten.0f.html#sirius

Fred Patten

For those who do want a story about a human mind in a dog’s body, I recommend the novels “The Dog Days of Arthur Cane” by T. Ernesto Bethancourt (Holiday House, October 1976), “Fluke” by James Herbert (New English Library, November 1977), “Lady; My Life as a Bitch” by Melvin Burgess (Andersen Press, September 2001), and the novella “A Matter of Form” by H. L. Gold (Astounding Science-Fiction, December 1938; reprinted in a half-dozen anthologies of “great science fiction”). I am deliberately avoiding the novelizations of Disney’s “The Shaggy Dog”. The movie version of “Fluke” is good, too, but it changes the plot considerably.

Fred Patten

I can't resist quoting this from Roz Gibson's LiveJournal. She attended a rock concert last night; probably the final performance of a long-time band before the musicians all retire. "At least the other guys there were gracefully accepting their hair loss. It reminded me of when I saw Dean R. Koontz at ComiCon and all I could do was stare at this awful rug he had on. Honestly guys, accept the hair loss with dignity. Women prefer that to a rug, which just makes you look like an idiot." In the 19th century, aging composer Franz Liszt was almost as famous for his flamboyantly obvious toupee as his virtuoso piano playing.

Fred Patten

Post new comment