Review: 'Top Dog', 'Dog Eat Dog' and 'A Dog’s Life', by Jerry Jay Carroll

Just running at first. Nothing before that. No memories of childhood and family. No early struggles. No career. No friends. No opinions. No country, city, neighborhood, no home where I laid my head at day’s end. No idea how I spent those days.

Running. One minute oblivion and the next I’m in a forest, shafts of the dying day falling through the trees and dappling the ground with patterns of light and dark. Quail scurry, small animals freeze as I pass. I have no questions about my place in the scheme of things. The wind is in my face and nothing seems more natural than running. It’s the beginning and the end and everything in between.

But there’s something wrong. I detest exercise. If it didn’t send the wrong message, I’d step from the Rolls and ride a sedan chair across Wall Street to the lobby elevators. The times what they are, my bearers would be a multicultural lot, a rainbow of muscular young men raising me above the mob. So some fragments of memory flash like strobe lights in a vast and dark chamber.

The flicker of feet beneath catches my eye. But they aren’t feet. They are paws. Something soft and wet bangs the side of my face. My tongue. The realization slowly dawns as I run. I’m a dog, a huge dog. (Top Dog, p. 1)

One day, William B. Ingersol sat in an office high above Wall Street conducting corporate takeovers.

The next day, he was a big dog, surviving by instinct alone in a strange new world.

Same difference. (Top Dog, back-cover blurb)

William “Bogey” Ingersol is a notoriously ruthless financier under investigation by the SEC; a corporate raider who has bought companies to gain their assets then closed them, sending hundreds of people out of work. His guiding interest has always been, how can I make the most out of this? So when he becomes a mastiff-sized feral dog in the wild, he is too busy trying to survive at first to spend time worrying about what has happened to him. His human mind combined with canine instincts enables him to come out on top in fights with wolves and other predators.

Top Dog; NYC, Ace Books, September 1996, 0-441-00368-0 trade paperback $12 (330 pgs.)

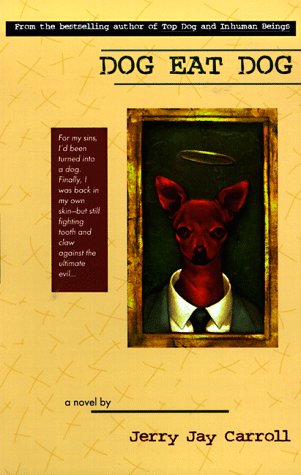

Dog Eat Dog; NYC, Ace Books, February 1999, 0-441-00597-7 trade paperback $12 (297 pgs.)

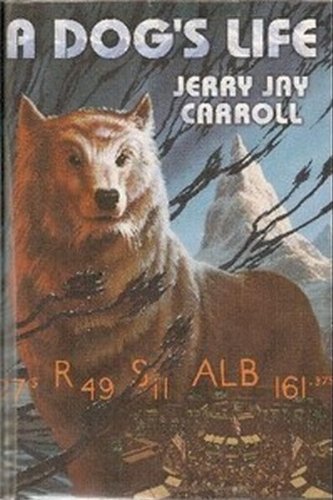

A Dog’s Life; Garden City, NY, Science Fiction Book Club, April 1999, SFBC #18131 hardcover $12.98 (490 pgs.)

Bogey finds that he can talk with other animals like badgers, stags, and Quick the fox, but they don’t know anything. Did some human enemy cast a spell on him? Has he died and been reincarnated as a dog?

Maybe I had made a pact with the Devil the way what’s-his-name did and welched on the deal. I got dragged to an opera in Italian on that very subject. I fell asleep, so any tips I might have picked up for dealing with Satan were lost. I wouldn’t think you’d want to screw around with him, but maybe I was desperate. Short on a margin call or something. (p. 18)

Is he still on Earth? Not with monsters like he and Quick see hiding under a bridge.

They were wet-looking and kind of purplish with warty lumps all over. Greasy, lank hair hung down over their faces. They motioned with thick arms. They had squashed-in mugs with yellow fangs and red eyes. Jesus, what a sight. (p. 19)

Quick identifies them as trolls. “Trolls. I was in a goddamned fairy tale.” (ibid.)

The animals of this world, the Fair Lands, may not know anything about Bogey’s Earth, but they know enough to stay on the sidelines in the battle between the Two Legs (Middle-Ages humans) and monsters like the trolls and others that Bogey has never heard of, the Uulebeets and the Pig Faces, the Mogwert and Gutters. He meets them sooner than he wants to. However, Bogey realizes that if he ever wants to get back to his world, he needs to get some answers from somebody in some position of power. Somebody who might know why he’s a dog. Especially if somebody on the monsters’ side is already looking for him.

Toward the middle of the afternoon I saw something far ahead that looked like a finger. Fate giving me the middle one, I thought. When we got closer I saw it was a snake, coiled and swaying in a way that would be hypnotic if I were a rabbit or a white rat.

‘Let’s go around,’ Quick said. ‘I hate those thangs.’

That was all right with me. We started to detour when the snake spoke.

‘What’s your hurry?’ He had kind of a fruity Oxbridge accent you hear on Masterpiece Theater. His forked tongue flickered in and out. Jet-black eyes like currants. ‘Can’t we talk?’

‘No thanks,’ I said.

‘You might learn something.’

I slowed. ‘Like what?’

‘Come closer.’

‘Don’t trust him,’ Quick whispered. (p. 35)

Bogey decides the other wild animals are not strong or organized enough to fight the monsters; also, staying in the wild is ultimately a losing proposition:

There are more ways to get hurt in the wilds than I like to think about. Step in a hole and break a leg and it’s a death sentence for sure. But even a sprain would be doom because you couldn’t catch anything to eat. Other risks – a snake bite, a big cat dropping from a tree and severing your spine with one bite. Or make a tiny mistake in timing when you pounce and get an antler or horn in your gut. No way you recover from that. Infection sets in and you’re history. Lap up bad water and get parasites that weaken you and make you a mark. What about rabies and distemper, not to mention Mogwert and all those monsters? (p. 49)

So he switches to the Two Legs, but he finds out that he cannot talk to them; they only hear barking. And they don’t believe in the monsters until too late. It seems that, whether it is this world or another, life tends to be the age-old battle between Good and Evil, after all. In this world, it is more direct; the forces of Good and Evil – or the Bright Giver vs. the Dark One, are personified through their spokesmen Helmish the angel vs. Zalzathar the evil wizard and his Mogwert legions. Bogey has been brought to the Fair Lands and turned into a dog through an accident in their cosmic battle, but it turns out that he can make the crucial difference and bring victory to whichever side he joins.

Top Dog is less an anthropomorphic novel than a religious allegory similar to C. S. Lewis’; but it is full of talking animals. Good vs. Evil; which will Bogey choose?

Top Dog is less an anthropomorphic novel than a religious allegory similar to C. S. Lewis’; but it is full of talking animals. Good vs. Evil; which will Bogey choose?

Bogey is Bogey, whether man or dog. Which side can offer him the best deal?

Top Dog is a unique fantasy, called “The Shaggy Dog meets J. R. R. Tolkien” by Kirkus Reviews; and one that Ace Books thought highly enough of to publish as a $12.00 trade paperback when its other s-f/fantasies were $5.99 regular paperbacks, with an “arty” painted cover by Joel Peter Johnson. Readers liked it, too, and demanded a sequel. They got one, Dog Eat Dog (Ace Books, February 1999, cover also by Johnson). Most fans felt that it was inferior because it is set back on Earth, not the intriguing fantasy world of Top Dog, and the cast is almost all human most of the time.

Dog Eat Dog is set about three years after Bogey awakens from his “coma” in his human body. He was almost immediately tried for embezzlement and convicted (he was technically guilty; the fact that he had already replaced the money before his arrest was considered irrelevant), and imprisoned for over a year before having his sentence overturned on a technicality. He has been trying to reform his life since choosing Good just before returning to Earth, but nobody will believe him. The public considers his new philanthropy as just another setup for some kind of unethical financial killing.

Bogey has retreated to his West Coast mansion, where he lives alone except for Havl, his Czech manservant (and the appropriate mansion staff). From his “retirement”, he learns that Bernard Soderberg, a financier even richer and more ruthless than he used to be, and who was the real target of Zalzathar to become a dog, is retiring from business to enter politics. He still has an affinity for dogs since becoming one of them (he can still understand their speech, which he does not reveal), and has become identified as a “dog nut” who will take in any stray or abandoned dog. He has 47 dogs in his kennels, and gets new dogs faster than he can find homes for them. He is constantly harassed by Rita Rutaway, a humane society officer who regularly cites him for having more than the legal limit of ten dogs on his property, and brands him as a scofflaw when he regularly pays the fines rather than give up the excess dogs to be euthanized. The dogs warn him that “something” is coming.

All this is just setup. One of Bogey’s neighbors is torn apart. Bogey’s dogs are blamed, and his pointing out that many of them are little lapdogs and that they have all been locked in their kennels just gets him suspected of deliberately covering up for them. Bogey recognizes the manner in which his neighbor was torn apart as typical of the Pig Faces of his fantasy world. Clues lead him to believe that, although the Bright Giver and the Dark One have conceded to the Bright One’s victory on this world and moved on to another dimensional battlefield, the Dark One’s minion Zalzathar wants vengeance against Bogey and has come to Earth with his Pig Faces to destroy Bogey’s life. Bogey puts his old financial ruthlessness to outguessing and combating Zalzathar’s schemes, and learns that Zalzathar’s vendetta against him is just to pass the time. Zalzathar’s real goal is to make Bernie Soderberg the next president of the U.S., as the first step to making him the antichrist.

Can Bogey stop him? Bogey has his old financial “insider” contacts and can reactivate his old black ops team, but are they sufficient against “all the forces of Hell”? Romance enters this sequel in the form of Dr. Alex Epperly, a psychiatrist from the Stanford Medical Hospital to whom Bogey is referred to “cure his delusion” that he was a dog in a fantasy world while his body was in a coma, and whom he comes to love. Bogey eventually becomes such an annoyance that Zalzathar changes him into a dog again; a helpless Chihuahua this time.

Can Bogey stop him? Bogey has his old financial “insider” contacts and can reactivate his old black ops team, but are they sufficient against “all the forces of Hell”? Romance enters this sequel in the form of Dr. Alex Epperly, a psychiatrist from the Stanford Medical Hospital to whom Bogey is referred to “cure his delusion” that he was a dog in a fantasy world while his body was in a coma, and whom he comes to love. Bogey eventually becomes such an annoyance that Zalzathar changes him into a dog again; a helpless Chihuahua this time.

I yelped and skidded to a halt on the wet grass. It was a German shepherd.

‘What’s this, a rat?’ he growled.

‘N-n-no.’

He gave me a thorough inspection as I stood rigid. This satisfied him that I told the truth. I was lucky at that. One of the terrier breeds would have snapped my neck with one shake without asking any questions. A collie and some kind of hound drifted up through the fog and gave me their own nuzzling once-over. That meant Alice had released the dogs for a run. Zalzithar must not have realized.

‘Wolves are after me,’ I said with a gasp. They snorted skeptically. ‘I’m telling the truth. Any minute now.’

‘There’re no wolves been smelled around here,’ a Scotty who arrived scoffed. ‘Never has been. Some say there’s no such thing.’ As he spoke, the wizard released the wolves. They howled as they came after me. The dogs threw up their heads.

‘This squirt’s telling the truth,’ the hound said. (pgs. 239-240)

So Dog Eat Dog finally develops an anthropomorphic aspect, but not until page 238 of the 297-page adventure, and then for less than twenty pages. Dog Eat Dog is also a satisfying and unique fantasy, and very different from Top Dog, but it is much less anthropomorphic. Furry fans take warning.

The two have also been published together as A Dog’s Life by the Science Fiction Book Club, in April 1999 (cover by Romas Kukalis).

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Just running at first. Nothing before that. No memories of childhood and family. No early struggles. No career. No friends. No opinions. No country, city, neighborhood, no home where I laid my head at day’s end. No idea how I spent those days.

Just running at first. Nothing before that. No memories of childhood and family. No early struggles. No career. No friends. No opinions. No country, city, neighborhood, no home where I laid my head at day’s end. No idea how I spent those days.

Comments

I have these (as A Dog's Life) and Top Dog is actually probably one of my favorite books.

Books and dogs are both mens best friends. And I love to have them both together.

Post new comment