Review: 'The Streets of His City and Other Stories', by Alflor Aalto

This collection of two novellas and two short stories are prequels to Aalto’s first novel, The Prince of Knaves (Rabbit Valley Comics, March 2012). In that novel, Prince Natier of Llyra, a fox, escapes assassination in a plot to overthrow the monarchy. He disguises himself as Rivard, a commoner (a disguise that he has used often in the past), and observes quietly as a laborer while the palace announces that he tried to kill the king before fleeing, and that the badly-wounded King Rasdill is incommunicado while he is healing, leaving the kingdom in the paws of the Royal Secretary, the squirrel Riius.

This collection of two novellas and two short stories are prequels to Aalto’s first novel, The Prince of Knaves (Rabbit Valley Comics, March 2012). In that novel, Prince Natier of Llyra, a fox, escapes assassination in a plot to overthrow the monarchy. He disguises himself as Rivard, a commoner (a disguise that he has used often in the past), and observes quietly as a laborer while the palace announces that he tried to kill the king before fleeing, and that the badly-wounded King Rasdill is incommunicado while he is healing, leaving the kingdom in the paws of the Royal Secretary, the squirrel Riius.

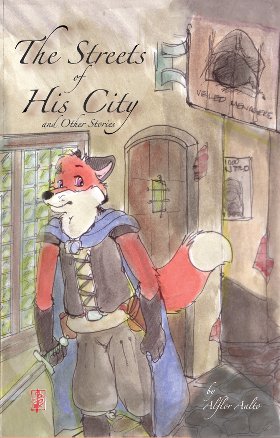

Rabbit Valley Comics, Sep. 2012, trade paperback $20 (259 [+ 1] pgs.; illustrated by Fennec; on Amazon)

I would like to thank my sister Sherrill for buying this for me at Rabbit Valley's table at CaliFur IX. Rabbit Valley does not send out review copies.

The Streets of His City, pages 1–119, begins with Prince Natier returning to the palace, exhausted, after an earlier assassination. His mother has been murdered during a diplomatic visit of the two to a fractious province, and he barely escaped. His father is delighted that they were not both killed, but Natier feels guilt.

‘She was killed, Your Majesty… It is a miracle your son made it back in one piece.’

He saw tears forming in his father’s eyes. ‘Did they find the body?’

‘No, Your Majesty, the entire town was overrun.’

‘How?’

‘We do not know.’

Natier knew; he knew all too well. It was all his fault.

He didn’t know what his father would do if he found out, so he kept quiet. (p. 1)

It is established immediately that Natier hated the restrictions of court life as a child:

His new room was much bigger than his old one; the toys were gone, too. They were replaced with a large bookcase and an elaborately-carved writing desk. Everything seemed very serious and adult. Natier didn’t mind. If anything, he wanted to leave his childhood behind as quickly as possible. It was a part of his life that he wanted to forget; between being isolated from everything by his overprotective mother and the perfect antithesis, having to beg and barter his way across the country to get home, Natier hoped that he would fare better in his life as an adult. (pgs. 1-2)

Natier gets his wish. The Streets of His City tells how Natier establishes his double identity as the street thief Rivard, and makes his first friends and enemies among the thieves’ guild.

“Just Like That”, pages 121–127, is an X-rated trifle. In The Streets of His City, Natier as the thief Rivard has need to hire the pretty-boy catamite Alir (rabbit) to create a distraction. In “Just Like That”, Rivard returns later to the Silk Peony male brothel to experience Alir’s charms for himself.

Their Labors of Love, pages 129–235, begins:

And now, we will observe the same series of events from the point of view of another, a young raccoon named Sirius. And maybe, just maybe, we will see that not all things are as they had first appeared …” (p. 129)

This story starts a few days earlier with “a young raccoon named Sirius” breaking up his relationship with Alir. Sirius, a minor character in the first story and the son of Werill, Prince Natier’s personal servant, can’t bear having a lover who is a professional concubine, having sex every night for money. Despondent, Sirius meets another handsome rabbit, Kaarper, who also works in the palace. A new relationship between Sirius and Kaarper starts to develop, bringing Sirius out of his depression. But since this story comes right after The Streets of His City, in which Kaarper meets a messy death, the reader knows that Sirius is doomed to be heartbroken.

Don’t be too sure. The reader will get a big surprise when Their Labors of Love suddenly shifts about halfway through to an entirely new direction.

“The Looking War”, pages 237–259, features Count Trivus (fox), the Commissioner assigned to find a spy in the royal palace of Llyra; Lord Orrin (raccoon), a Llyran nobleman; Kelan (rabbit), Count Trivus’ assistant; and King Rasdill, Secretary Riius, and others of the palace with whom the reader is familiar. Trivus and Orrin are lovers, and when Orrin is suborned by an enemy nation to become the spy, the two make a game of Trivus pretending to almost catch the spy, who always escapes at the last moment. Their game, and Orrin, are put into real danger when Trivus is given Kelan to assist him. The rabbit is very serious about unmasking the spy, and is too smart to be fooled for long.

The Streets of His City and Other Stories is one of those annoying books that is easier to nitpick for its flaws than to praise for its virtues; so let’s concentrate on the latter first. This is a fine funny-animal book. No reason is given for the setting to be a Renaissance European kingdom inhabited by talking animals (one of which, the raccoon, is strictly a New World animal), but it is a very good example of that type. Aalto bolsters the illusion with references to animal traits such as the sharp sense of smell, and frequent language like “tip-pawed” for tiptoed. The first and longest story does not feature any homosexuality, but the others are definitely for adult readers. Aalto successfully plays a tricky blending of two personalities/characters in two stories, Prince Natier’s languid aristocratic reality and Rivard, the street-wise common thief that he hopes to become; and Sirius’ two rabbit lovers, Alir and Kaarper. The four stories are connected smoothly; this book is really a novel disguised as a collection.

The Streets of His City and Other Stories is one of those annoying books that is easier to nitpick for its flaws than to praise for its virtues; so let’s concentrate on the latter first. This is a fine funny-animal book. No reason is given for the setting to be a Renaissance European kingdom inhabited by talking animals (one of which, the raccoon, is strictly a New World animal), but it is a very good example of that type. Aalto bolsters the illusion with references to animal traits such as the sharp sense of smell, and frequent language like “tip-pawed” for tiptoed. The first and longest story does not feature any homosexuality, but the others are definitely for adult readers. Aalto successfully plays a tricky blending of two personalities/characters in two stories, Prince Natier’s languid aristocratic reality and Rivard, the street-wise common thief that he hopes to become; and Sirius’ two rabbit lovers, Alir and Kaarper. The four stories are connected smoothly; this book is really a novel disguised as a collection.

One of my criticisms of The Prince of Knaves was that Natier’s double life, as a palace nobleman all day and a street thief all night, would be unrealistically exhausting. Aalto deflects this criticism here with frequent mentions of, “After the long day he’d had, Natier didn’t think it possible, but he was no longer tired. A new, brisk energy permeated him.” (p. 27), and, “Again, Natier resisted the overwhelming urge to fall asleep.” (p. 39)

Aalto also makes Natier’s double-life more plausible by hints of an irresistible personality urge:

If his father found out about his night-time activities, the consequences could be severe; he could even lose his inheritance. On the other paw, something about the adrenaline rush that came with being a thief felt simply indescribable. Rivard took another deep breath and approached the ledger. (p. 30)

The text is enhanced by over a dozen full-page illustrations by Fennec, who also did the wraparound cover.

Criticisms … Aside from the first-page off-stage mention of Natier’s mother, there is not a single female in the book. The all-male cast reduces this from an adult story to a boys’-adventure tale. Natier is moved from a room with his childhood toys to one without them, and suddenly he’s an adult overnight. His new room contains a forgotten Secret Passage that nobody else knows about, but which he stumbles across in about five minutes. His new night life as a member of the thieves’ guild seems about as dangerous as little boys playing pirate; it’s a shock when somebody actually gets killed. The cryptic mentions of the offstage mission on which Natier’s mother is killed are never explained. (Is Aalto saving this for another book?) Rabbit Valley’s proofreading is inconsistent, too. There are few misspellings, but the title varies between The Streets of His City and Streets of His City, and The Streets of His City and Other Stories and Streets of His City and Other Tales. There is no Table of Contents or running title heads on the pages, making it difficult for the reader to tell where one story ends and another begins.

The Streets of His City and Other Stories is not perfect, but its virtues far outweigh its defects. Unless you are put off by scenes of male homosexual romance, you should enjoy this book.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

Um... the price is way wrong... It's $20.00 at Rabbit Valley....

http://www.rabbitvalley.com/item_8563_3829___The-Streets-of-His-City-and-Other-S...

Hmm. You're right, it does cost that now, though Amazon lists it at $37; probably the original price.

My review format is to list books at their publisher's retail prices, not the discount price on a bookshop's website, even when it seems obvious that the official retail price is only designed to get people to order it at the discount price. In this case, the announced retail price of "The Streets of His City" was $37.00, and the $20.00 price is a markdown even when it is the publisher's own markdown.

Fred Patten

Fred,

The publisher's website is the list price of the book. Rabbit Valley Comics sells books at list prices. The list price is $20. The amazon.com price is the "markup" price thanks to dealing with Amazon's interesting payment policies. We also sell Associated Student Bodies Hardcover on Amazon.com for $45.99 (http://www.amazon.com/Associated-Student-Bodies/dp/0971988609) but our publisher site clearly sells the book for list price of $39.95 (http://www.rabbitvalley.com/item_4900_5539___Associated-Student-Bodies-Yearbook-...). Same applies to Circles Volume 1 paperback, Prince of Knaves on Apple's iBookstore, and many other examples.

Amazon is not the publisher. Rabbit Valley is. Rabbit Valley's price prevails.

Sean

--

Rabbit Valley Customer Service

Rabbit Valley Comics

5130 S Fort Apache

STE 215 PMB 172

Las Vegas, Nevada 89148

Phone: 702-291-8286 (Orders 11:00 AM - 5:00 PM EST)

Website: http://www.rabbitvalley.com/

Email: customerservice@rabbitvalley.com

Okay. You are in the position to know, on Rabbit Valley books, at least. I will tell GreenReaper to change this price back to $20.00, and I will list your catalogue price rather than Amazon.com's price on any future Rabbit Valley books that I review.

Fred Patten

Not a single female character. Wow. Guess that shouldn't surprise me in this fandom, but it does.

Well to be fair it is titled "The Streets of His City..."

Then again... I guess there were male characters in Little Women

Please name one female character in the latest Tintin film -- with the exception of Ms. Finch, who was around for about 10 minutes as Tintin's landlady. I'll wait.

My point is simply that there is absolutely no requirement for character genders in a story, nor does such a thing ruin a good book. And if it does for you, then you've got incredibly strange priorities.

Post new comment