Review: 'Divisions', by Kyell Gold

Divisions is set in Kyell Gold’s Forester universe (Waterways, Green Fairy, Winter Games, etc.), and is the third in the series featuring the tiger Devlin Miski and the fox Wiley Farrel (Out of Position, 2009, and Isolation Play, 2011). The series is narrated in the first person by both Dev and Lee in mostly alternating chapters.

Divisions is set in Kyell Gold’s Forester universe (Waterways, Green Fairy, Winter Games, etc.), and is the third in the series featuring the tiger Devlin Miski and the fox Wiley Farrel (Out of Position, 2009, and Isolation Play, 2011). The series is narrated in the first person by both Dev and Lee in mostly alternating chapters.

Each novel documents a year in their life. In Out of Position, 2006, the two seniors at Forester U. meet, become secret lovers, and at the conclusion Dev, on Forester’s football team, becomes the first “out of the closet” football player. Isolation Play, 2007, starts immediately after Out of Position and deals with the aftermath of Dev’s and Lee’s revelation: Dev’s hostile teammates, shocked parents of both, a reporter determined to use them in a sensationalistic story, and facing life after graduation.

Now in Divisions, 2008, Dev and Lee pursue equally their professional careers, their personal lives, and the results of their open homosexuality.

Divisions is a romance novel intended for an adult audience only and contains some explicit sexual scenes of a primarily Male/Male nature. It is not for sale to persons under the age of 18. (publisher’s advisory)

Sofawolf Press, January 2013, trade paperback $19.95 (xvi + 367 pages; on Amazon). Illustrated by Blotch.

Looking at Divisions objectively, there is almost no fantasy, save for the characters being anthropomorphized animals. This is a realistic novel about two young homosexual lovers beginning life after college.

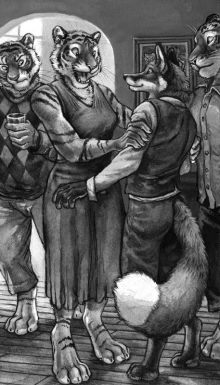

The opening line is, “From the other side of the menu, Father says, ‘I filed for divorce.’” (p. 3) Lee’s homosexuality has ended his parents’ shaky marriage, his father accepting it while his mother joins a militantly anti-gay religious group. Dev’s full extended family of ten tigers have accepted his homosexuality, and they invite Lee and his father to an after-Thanksgiving get-acquainted social gathering.

[Dev:] We meet up with Aunt Ania first, and my formal thought-out introductions turn into simply, ‘This is Lee,’ when she turns.

Aunt Ania looks like my mom: same height, same stripes, just about, same build. But Mom is still on her first husband, and her older sister is twice divorced. ‘All the money and none of the dead weight,’ Ania likes to say. She wears flashy jewelry that my dad grumbles about after she leaves, and her dresses are always out of the latest Vogue.

Under all that, she is definitely family. She greets us with a smile as bright as my mom’s, and turns it full power on Lee. ‘What a pleasure to meet you,’ she says. ‘So you’re the one turning my nephew’s head.’

‘None of the running backs he’s faced have managed to,’ Lee says.

Ania looks to me as she says, ‘How charming.”

“Football humor,” I say. “A ‘swivelhead’ is a guy who has to keep turning his head because the player he’s supposed to be tackling is running past him.”

‘Oh, I see.’ She plainly doesn’t. ‘So how did you two meet?’

He tells variations of this story three times in my hearing that night. ‘We went to the same college. I was a football fan, he was a player.’

‘And how did you start dating?’ Aunt Mariya wants to know, later.

‘Well, I had to talk him into it.’ Lee smiles, aware of Uncle Roger over her shoulder and the cup of buttered rum he’s holding in his paw.

‘I bet you did.’ Uncle Roger is not as big as me or father—not as tall, that is. He’s as big around as both of us put together. ‘I bet you were real fuckin’ persuasive. Foxes.’

‘I’ll take that as a compliment,’ Lee lies with a long fox smile. (pgs. 15-16)

Dev and Lee are starting their first jobs; Dev as a linebacker for the pro Chevali Firebirds team, and Lee as a football talent scout. Dev and Lee set up housekeeping together. (Their steamy romantic scenes are what gets Divisions its “adult audience only” rating.) Dev’s family life sinks into the background as his relations with his new teammates is emphasized. Some without girlfriends ask Dev to have Lee show them what the gay community is like:

[Dev:] We grab a big table at the Unicorn and their cocktails do look pretty fabulous, in a couple senses of the word. I get something called a Cinnamon Swish, and Lee orders a Tangerine Sparkle. The other guys order cocktails, except for Kodi, who orders a beer, and then they sit around and watch the rest of the patrons, who are also watching us.

‘Six big guys sitting in a gay bar,’ Lee says. ‘Of course you attract attention.’

But nobody really comes up to us. When our drinks come, served by a slender, attractive cheetah in shorts and an open short-sleeved collared shirt, Ty takes a sip of his and then says, ‘It looks so normal in here.’

‘Except that it’s all guys,’ Vonni says.

‘Yeah, but they’re not doing anything.’

Lee licks the rim of his glass. ‘If you want to see that, there are a couple other places…’

‘No, no.’ Vonni laughs.

‘Well, gay guys are just people, you know? We like to drink in a safe place and hang out together. We don’t whip out our cocks at the least provocation.’

‘See, Pike?’ Ty elbows him. ‘You ain’t gay.’

‘Har har.’ Pike drinks from something cloudy and creamy. ‘Jury’s still out on you, right?’

Ty grins. ‘I got no worries.’ (p. 91)

Lee, on the other paw, aggressively takes his father’s side in establishing a new life alone, while becoming openly hostile to his mother’s virulently anti-gay “Families United” group. Lee learns that they almost surely pressured a gay college football player like Dev into committing suicide:

[Lee:] Then there’s an e-mail from Alex, the rabbit from the Dragons. The e-mail’s titled, ‘Thought you should know about this.’ I click.

It starts out with him hoping I’m doing okay, asking if I want to get together for lunch sometime. I guess I should tell him I’m living three days away now. He goes on: ‘Hey, you added this guy Vince King to the Dragons list a month ago and we just got this notification on him. College says he passed away on Saturday. Don’t know the details, but you were interested in him and it’s kind of an excuse to get in touch ‘cause I felt shitty for not writing

when I saw it, y’know?’

Aw, crap. Most of the good mood I had from moving in evaporates. I type out a quick, numb response. ‘Thanks for the heads-up. I’m in Chevali but I’ll be back in Hilltown sometime this fall. Let’s get together.’

And then I have to go look at the Cobblestone College website. The athletic section has a page mourning the passing of Vince King, and a link to the article in the kid’s local paper.

That article just says that he was found dead in his family’s home the day after Thanksgiving. The lack of detail smells weird to me. If it were a car accident, it would say ‘Car accident.’ If he had some kind of disease, it definitely would have mentioned a stay in the hospital. But nothing. No ‘heart attack,’ no ‘brain aneurysm,’ no ‘fell off a ladder.’ So it was the kind of death they wouldn’t want publicized. Like a suicide. And a gay kid committing suicide, well, there’s been a few of them lately.

I know he’d been having a hard time when he wrote to Dev, but…

Then I get a sinking feeling. I haven’t checked Dev’s e-mail since before the holiday. It had trickled off since he came out, and I figured I’d get back to it after the Pelagia game. I’m sure there’s nothing there. Sure of it. But I’m still terrified, when I log in, to look, and my finger hesitates over the mouse click before I finally open the inbox.

God, what was his e-mail address? I scan the list, look through it again. Nothing from anyone with the name King, as far as I can tell. And I’m relieved that he didn’t reach out while I wasn’t looking, but I’m also disappointed. I wish he’d thought he had someone to talk to.

I do another web search for his name, filter it to prioritize recent results, and then I get a weird hit. ‘Praying for the soul of Vincent King,’ the page is titled, on a website with an all-too-familiar name: familiesunited.org. But when I click on the link, the page isn’t found. Thank goodness for search engines; I can see a cached version that looks like it was stored last Sunday.

It asks the ‘faithful’ to join the congregation (which one, it doesn’t say) in prayer for the soul of the son of Paul and Vanessa King, who has been ‘tempted by the homosexual lifestyle’ and who has been ‘receiving lies as truth from homosexuals seeking to lure him into a degenerate lifestyle.’

It gets worse the more I read, but the thing is, most of it doesn’t sound specific to Vince. It ends with a repeated exhortation to keep this young boy in the reader’s prayers—doesn’t even say ‘young fox’ or ‘young bear’ or anything. I snoop around the website and see a bunch of different prayers with a lot of the same terminology. Some of them have pictures, school pictures with the young fox, or ringtail, or rat, anywhere from high school juniors to college seniors, looking bright and smiling against that uniform school picture background. Pictures supplied by the parents, not the cubs. Many—most—of the pages are about poor boys tempted by homosexual degenerates, but I find two youngsters in danger from the evils of drugs.

When I click around the website, I find other charming essays posted. Things like how all homosexuals ideally want to fuck little boys. How the homosexual agenda includes a complete redefinition of marriage to include farm animals. How homosexuality is a disease that has a cure. (pgs. 54-56)

This spurs Lee into seriously considering rejoining the gay militant activists that he used to be a member of before he met Dev.

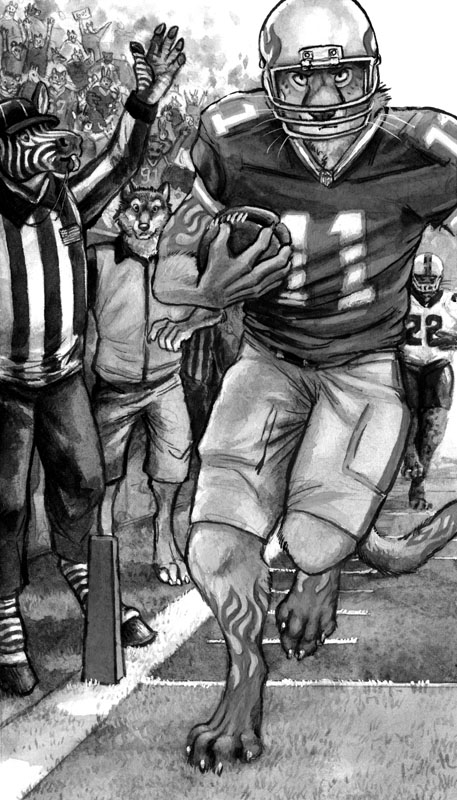

What effect this has on his relationship with Dev and on his new job is shown at length. There is even the possibility of Lee being hired by the Firebirds to set up and run a gay community outreach program. Scenes of Dev practicing with the Firebirds, and the Firebirds’ scoping out their UFL division opposition, lead to hot & heavy descriptions of Dev’s games:

[Dev:] But Hellentown is playing pretty inspired defense, too. They double-cover Strike on pretty much every play. Jaws runs well, but when we get down to their twenty, Aston underthrows Strike in the end zone. The cheetah lunges forward, not in time to stop one of their cornerbacks from grabbing the ball out of the air. Strike tackles him immediately, but it deflates us.

We were so close and now we have nothing to show for it.

I go back out onto the field with more determination, and as Pike breaks up one of their run formations, Gerrard and I bring down their running back, a big elk, for a two-yard loss. On the next play, Carson tackles the tight end at the line. We rush the lion on third down, and he has to throw the ball away. So they don’t get any points off the turnover, and we feel good.

The problem is that Aston is trying too hard now. He throws too hard, too long, and he doesn’t look for Strike at all on the next series. Ty catches a nice pass for a ten-yard gain, but we can’t get past midfield, and we have to punt it back to them.

At least we have better field position. This gives us on the defense more incentive to keep them contained, and we do, until most of the way through the second quarter. Their deer, the finesse back, slips past Brick, jukes past Gerrard. I run after him, but it’s Norton who tackles him, well into our territory.

‘Hold tight!’ Gerrard yells at us. ‘Hold tight!’

That fox, 83, is ready again, and I know they’re going to throw to him. I’m ready, and when the play starts, I watch for him to break. I bump him at the line, throwing off his timing, and then he breaks for the sidelines. It was probably a precision play, or else the quarterback is throwing away from me, because the ball goes off the fox’s outstretched paw, out of bounds to the side.

Momentum carries me into him; I put my paws out to stop myself. Again, he growls and shoves me and says, ‘I told you, homo, I’m not your cocksucking boyfriend.’

I can’t see his face, but if I could, I feel like I’d punch it. Instead, I back up, holding my paws up, and say, ‘I know you’re not. My boyfriend can catch.’ (p. 312-313)

Divisions is full of realistic conversations ranging from polite social discourse to raunchy locker-room banter. There are no dramatic events of the suspense-thriller variety; just a very well told tale of two young gay men making a life for themselves. Read wherever there is any interest in serious gay fiction, fantasy or not.

The wraparound cover is by Blotch, who also drew ten full-page interior illustrations. Divisions is also available in a $39.95 hardcover edition with a bonus short story, “Heart”.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

I'll be sure to get it for my Kindle once it's available.

Wow! i like a books. But where my new books 3. do you forgot call phone my brother, on Monday right now! you can't to wait.. Just i wants see that books. it's her.

Post new comment