Review: 'The Singing Tree'/'The White Fox', by Brian Parvin

It is mostly forgotten today, but when The Singing Tree was published in England in the mid-Eighties, especially in its American paperback edition as The White Fox, early Furry fans told each other, “You’ve got to read this!” When the first Furry specialty publishers emerged at the end of the 1990s, some of the novel’s diehard fans urged that they try to bring out a new edition of The White Fox.

It is mostly forgotten today, but when The Singing Tree was published in England in the mid-Eighties, especially in its American paperback edition as The White Fox, early Furry fans told each other, “You’ve got to read this!” When the first Furry specialty publishers emerged at the end of the 1990s, some of the novel’s diehard fans urged that they try to bring out a new edition of The White Fox.

This was not bad for a novel that was unknown in most American public libraries and was only briefly available from an obscure American paperback publisher.

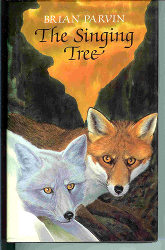

“The Singing Tree”, by Brian Parvin. Illustrated. London, Robert Hale, Ltd., March 1985, 185 pages, £8.95; ISBN: 0-7090-2159-3.

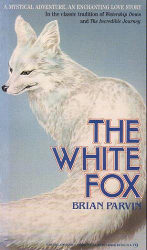

“The White Fox”, by Brian Parvin. Illustrated. Los Angeles, Medallion Books, July 1986, 238 pages, $3.50; ISBN: 1-55627-012-7.

Most information about the author mentions The Singing Tree only in passing as a book that he wrote before specializing in Western novels in 1992 (Buried Guns, Trail-Scarred, Shoot to Live, The Gun Master, and forty-four others). According to the London-based Black Horse Western online newsletter in 2007,

Brian Parvin, who writes his westerns as Dan Claymaker, Jack Reason and Luther Chance, hails from Shropshire, a county in the west of the English Midlands, bordering on Wales. It is fine pastoral country with hills and woodland, agriculture and dairying. Brian -- and Dan, Jack and Luther -- live in its beautiful, medieval market town, Shrewsbury.

A mystical adventure, an enchanting love story. In the classic tradition of “Watership Down” and “The Incredible Journey”, the American paperback is blurbed. Combined with a bleak s-f plot, that is. Chalon, a starving dog-fox trying to survive in the almost-lifeless wasteland a hundred seasons after the Great Death, tumbles into an arid blast crater where he discovers a dying white vixen:

Chalon’s hindlegs pushed at the ground and he eased his body away from her. It was time to explore the crater again, to discover where, if at all, there was hope of escape; some way or means by which he could reach the outcrop and, more importantly, some way he could find to drag the vixen with him to water. If she did not drink soon and had not done so by the time the sun was high, she would surely die.

He padded round her, seeing her for the first time in the light of day. She was very young and, even allowing for the ordeal of her hunger, as slim as a sapling. But her fur and the density of her coat were as calm and soft as snow. This, he decided, was no ordinary Whiteface. There seemed none of the viciousness about her, the meanness of mouth by which the breed had become known in the seasons since their first appearance after the Great Death. Chalon knew well enough the story of the Whitefaces’ coming, of how they had appeared in the High Peaks as a strange mutation, a hideous consequence of the Burning Air that had followed the Great Death; of how, in less than three seasons, they had become a breed of pure white foxes, outlawed by their common kind and forced higher into the peaks where they lived among the rocks and caverns of a desolate land.

[…] It was said that even the few men – those still alive in their outposts of retreat – who ventured to the High Peaks held the Whitefaces in fear and would journey miles around them rather than face their anger. But this vixen, so soft and white and still, could not be one of such a breed, thought Chalon, yet such thoughts did nothing to explain why she was here or why, as he now felt certain, she was alone. (U.S. ed., pgs. 11-12)

The vixen has fled from the murderous infighting among the Whitefaces and is trying to find the legendary land of the Singing Tree. Chalon knows the tales:

Had not Chalon’s great-grandfather dog fox, the grey Wasden, told of how some believed it was written that the animal kingdom alone would survive the Great Death and discover new lands where there were no men and the seasons were at peace with growth; where there were green fields and pastures, thickets, woodlands, valleys, streams, open spaces and the gentle roll of hills, and that there were those who would make such a journey – those, he had said, who sought an answer to its whereabouts and placed their faith in The Singing Tree’s existence? (pg. 24)

Since there is little hope of survival in his desolate homeland, Chalon decides to accompany and protect her on her quest.

But would the south welcome her; were there mutations in the green fields and woodlands; was the new land a land for all, or did it guard its chosen few in some ritual of selection and rejection? (pgs. 24-25)

This is a rambling journey novel. Chalon and the nameless Whiteface vixen travel through unknown wastelands, crossing through or bypassing one deadly stretch of ground after another, some of which are natural hazards like rapids and some relics of the Great Death such as a vast Plain (a dried-up lakebed) covered by a “death cloud” of poisonous fog. They are trailed by four murderous Whiteface foxes who are determined to kill the vixen, and they encounter villages of brutal human hunters who lust after the vixen’s snowy pelt. But they are also aided by a series of friendly animals – Ghek the buzzard, Maychep the river otter, Briggan the badger, Alom the red squirrel, and Sugg the wild [feral] cat – who pass them on ever southwards.

“I warn you now – the true test of your endurance has still to come. Whatever your success so far, however you may have achieved it, whatever the effort, these are as nothing to all that lies ahead. Your path, my friends, is already destiny.” (pg. 105)

This speech by Briggan is symptomatic of both the main strengths and weaknesses of the novel. It is reassuring yet confusing to be told that they are destined to succeed, but that the next peril may be more than they can survive. No matter how hard each obstacle has been, Chalon and the vixen are constantly assured that worse lies ahead; and the constant succession of perils eventually becomes repetitious. The fact that all the animals mysteriously know more about their quest than the two foxes do soon becomes annoying. Also, The Singing Tree is misleadingly blurbed as a love story. Chalon is considerably older than the vixen, and while they come to care deeply for each other, their relationship is closer to father and daughter than two lovers.

The Singing Tree is an enjoyable animal fantasy, but almost thirty years later it is hard to remember why early Furry fans considered it so special. The probable reason is that there were just not that many talking animal fantasies published as adult rather than juvenile novels in the 1980s. It is worth reading if you come across it, but there are enough other Furry novels for adult readers today that you do not need to seek this out.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

I read The White Fox back in the early '90's (based on some fan recomendations). It was a good book over all, but I agree. It's a hard one to find. At least I had a lot of used book stores that specialized in sci/fi fantasy in my area back then who were more than willing to go to book fairs to find these obscure paperbacks for me.

I found this little book in a charity shop yesterday tucked away on the back bookshelf, I saw the cover and title and was immediately on my way to the counter to get this preloved book, what a beautiful story for a couple of cold winter night reads, Thank You

Post new comment