Retrospective: Talking animals in World War II propaganda

You are probably thinking of the USA's World War II propaganda animated cartoons. There were certainly lots of them!

You are probably thinking of the USA's World War II propaganda animated cartoons. There were certainly lots of them!

Long articles could be (and have been) written on the adventures of Donald and Daffy Duck, Bugs Bunny, Gandy Goose and Homer Pigeon. In the last decade, most American propaganda cartoons have been re-released on DVD, so we can see them for ourselves; they are also on YouTube.

Volumes could also be written of the wartime funny-animal comic book and newspaper comic strip characters who fought the Axis, usually on the Home Front against saboteurs and hoarders. World War II's talking-animal propaganda novels are less well-known. In fact, they are forgotten today except in movie-adaptation credits. That’s too bad, as the books are still enjoyable reading.

The Allies

Cartoons

Cartoons

Probably the best-known wartime cartoons starring funny animals were Disney’s 1943 “Der Fuehrer’s Face” (Wikipedia), directed by Jack Kinney, with Donald Duck in Nutziland, and the 1944 “Commando Duck”, directed by Jack King, with Donald wiping out a Japanese airfield; Warner Bros.’s 1942 “The Ducktators”, directed by Norm McCabe, with barnyard parodies of Adolf, Benito, & Hirohito, the 1943 “Scrap Happy Daffy”, directed by Frank Tashlin, with Daffy Duck encountering a goose-stepping Nazi scrap-eating goat, and “Bugs Bunny Nips the Nips” [higher-qualiy visuals], directed by Friz Freleng in 1944, about which the less said today the better; MGM’s 1942 “Blitz Wolf”, directed by Tex Avery, with its Hitlerian wolf versus the American G.I. Three Little Pigs, and the 1943 “War Dogs”, directed by William Hanna & Joseph Barbera, featuring the mishaps of an Army K-9 trainee.

But all of the animation studios made propaganda cartoons, and many featured anthropomorphized animals: Terrytoons’ “Barnyard Blackout” and “The Last Round Up”, directed in 1943 by Mannie Davis, with Gandy Goose and Sourpuss Cat as Civil Defense wardens trying to enforce a barnyard Home Front blackout, and as soldiers blown to a funny-animal Germany where they find Hitler the pig with Mussolini as his pet monkey; Universal/Lantz’s 1942 “Pigeon Patrol”, directed by Alex Lovy, with Homer Pigeon trying to become a U.S. Signal Corp carrier pigeon and fighting a Japanese vulture; Columbia’s 1943 “The Cocky Bantam”, directed by Paul Sommer, with a rooster “Federal Bureau of Indignation” agent exposing Jap black marketeers on the Home Front; down to independent animator Ted Eshbaugh’s 1945 “Cap’n Cub”, directed by Eshbaugh & Charles Hastings, with an American bear cub pilot fighting against the Japanese monkey air force.

The British and Canadians made some wartime propaganda animated cartoons, but none featuring animal characters. The Soviet Union did not, either, although it did caricature Nazi U-boats and the Luftwaffe as anthropomorphized sharks and vultures and Nazi soldiers as a cross between a wolf and a pig, in 1941 Soyuzmultfilm Fascist Jackboots Shall Not Trample Our Motherland, directed by Aleksandr Ivanov and Ivan Ivanov-Vano, and The Vultures, directed by Panteleimon Sazonov. It also showed Hitler’s allies Mussolini (Italy), Horthy (Hungary), and Antonescu (Romania) as trained dogs performing for a demonized but human Hitler, in the 1942 Cinema-Circus, directed by Leonid Amalrik and Olga Khodataeva.

Comics

Carl Barks’ first Donald Duck short in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (#31, April 1943) was “The Victory Garden”, with Donald and nephews trying to defend his Home Front garden against three greedy crows.

Carl Barks’ first Donald Duck short in Walt Disney’s Comics and Stories (#31, April 1943) was “The Victory Garden”, with Donald and nephews trying to defend his Home Front garden against three greedy crows.

In the more adventurous Mickey Mouse newspaper comic strip, by Floyd Gottfredson, Dick Moores, & Bill Walsh, Mickey fought Nazi agents and U-boat crews (funny animals, of course) both on the Home Front and in the Atlantic. I won’t try to list all the minor patriotic creatures. Dan Gordon’s Superkatt, Ernie Hart’s Super Rabbit, and other now-forgotten funny animals either fought the Axis or regularly worked parodies of Hitler, Tojo, or their buddies into backgrounds and throw-away gags.

Novels and stories

Mr. Limpet

By the time that Warner Bros.’ 1964 The Incredible Mr. Limpet starring Don Knotts was made, nobody remembered the 1942 novel Mr. Limpet, by Theodore Pratt (illustrated by Garret Price, A. A. Knopf, January 1942, 144 pages). It was popular enough to go through two printings during the war. Nobody seems to know why Warner Bros. decided to film it as late as 1964. The movie was a mostly faithful adaptation of the novel, and WB got a perfect duplicate for Mr. Limpet in Don Knotts. Meek, henpecked Henry Limpet wants to help the war effort, but he is too puny to join any of the armed forces. He falls off a Coney Island pier and is transformed into a handsome fish who can still talk. He insists on using his piscine abilities to help the U.S. Navy, whether they believe in him or not, and he becomes instrumental in wiping out the Nazi U-boats in the Atlantic. (There has been talk for years about remaking Mr. Limpet with Jim Carrey, but nothing has happened yet.)

Mr. Limpet was published in January 1942, and internal evidence shows that it was written before the U.S. entered the War. America is still officially neutral, though the public expects Hitler to drag us into the war at any moment. The depiction of Hitler is mild compared to the savage lampoons of him after 1941. Hitler personally radios Mr. Limpet and practically offers him the Moon if he will join Germany against Great Britain. Mr. Limpet politely declines. Most tellingly, the novel is all about America vs. Germany in the Atlantic; Japan is not even mentioned. Nobody in America took Japan seriously until Pearl Harbor.

Francis and Francis Goes to Washington

The Pacific theater was left to Francis, by David Stern (also illustrated by Garret Price, Farrar, Straus & Co., October 1946, x + 216 pages). The novel is a fixup of fifteen short stories that Stern wrote for magazines like Esquire while serving on an Army newspaper in Honolulu during World War II. Francis, a disreputable-looking Army mule who just happens to be able to talk and fly, becomes the unlikely guardian angel of a nameless brand-new 2nd lieutenant fighting Japs in the Burmese jungles. In the fifteen adventures, Francis helps the officer to foil enemy attacks, expose Axis spies, and so on. The Army is ready to pin medals on the lieutenant, but he always insists on honestly giving the credit to Francis, which gets him sent to the psycho ward. As the stories progress, the Army brass reluctantly come to believe him and try to catch Francis in action, but he is too clever for them.

The Francis stories were popular during the War. The reader can tell in the last story that Stern didn’t really know how to end the series, and he was unsure how the public would feel about such martial derring-do during peacetime. Their popularity held up, and the book went through several printings. A couple of years later Stern wrote a sequel, a true novel: Francis Goes to Washington (front. by Garrett Price, Farrar, Straus & Co., September 1948, xii + 243 pages).

Mister Ed

Considering the time-frame of this article, I am tempted to include the Mister Ed humorous short stories by Walter R. Brooks, about an often inebriated talking horse and his equally drunken owner, Wilbur Pope, in Mt. Kisco, New York. Brooks wrote 25 of them for the popular magazines Liberty, The Saturday Evening Post, Esquire, and Argosy between 1937 and 1945.

So they are talking animal stories, and most of them were published during World War II. But they were not propaganda. The war was barely present in their plots, even as a Home Front element – one story briefly mentions gasoline rationing. Also, there was never a collection of the stories. The glory years of Mister Ed’s popularity were the 1960s, when the series (considerably cleaned up for the family audience) became a very successful TV situation comedy that was not related to any war. In January 1963 a cheap paperback collection of nine of Brooks’ 25 stories was released as a TV program tie-in; little more than a third, but better than nothing.

The 2nd lieutenant, now civilian Peter Stirling, returns to postwar life as an East Coast bank clerk. When his local Democratic party invites him to be its candidate for Congress, he feels honored – until Francis reappears to reveal that the Mayor, known to political insiders as “Slimy” Parker, is a corrupt boss who plans to use him as a patsy. Francis volunteers to be his secret campaign manager to keep him honest yet successful. Francis reveals himself to Peter’s girl friend Betsy Cupper, who is tired of being dismissed as “only a girl” and is delighted to become Francis’ partner in running Peter’s underdog campaign.

Francis Goes to Washington ends with Peter’s election victory, and the trio about to leave for Washington. A third book was obviously intended, but was never written. Stern bought a New Orleans newspaper in 1949, and spent the rest of his career running it. Also, in 1950 Stern sold the film rights for Francis to Universal Studios for $50,000, plus $50,000 for each of the six sequels released during the 1950s. Stern probably felt he could sit back and collect much more money from the film rights than from writing any more novels.

A more important reason may be – although this is a guess – that Francis Goes to Washington was less successful than Francis. It is certainly a much darker and more cynical comedy. With Francis, the reader could identify with the 2nd lieutenant as a very young, understandably inexperienced and bewildered American lost in the unfamiliar Burmese jungle. With Francis Goes to Washington, it becomes obvious that Peter Stirling isn’t just inexperienced; he is really stupid. He figuratively spends the novel with his mouth hanging open while Francis and Betsy treat him like a puppet. Francis is a story of America = Good vs. the Japs = Evil. Francis Goes to Washington is a story in which the antagonists are our own corrupt political establishment. The ultimate patsy is the U.S. voter. American readers couldn’t be expected to feel as good about this.

The Axis Powers

German cartoons

The Axis also featured animated talking animals in wartime adventures, though these were generic funny animals. There were no animal “stars”. The Germans were especially handicapped in that there were no major German animation studios, just individual companies run by their creator/directors, and the leading German animators were anti-Nazi and really did not want to make propaganda cartoons despite Propaganda Minister Goebbels’ pointed urging. In the 1940 “The Troublemaker” (“Der Störenfried”), a fox comes into a forest community but is driven off by a wasp air force. Though this shows hedgehog soldiers and wasp aerial fighters, they show no nationality and animation director Hans Held avoided pointing to any identifiable enemy. Even the fox is not shown as menacing; he is merely peaceably passing through.

Hans Fischerkoesen of the Fischerkoesen-Film-Produktion studio, considered wartime Germany’s best animator, steadfastly refused to include anything martial in his cartoons, and only “officially” featured an “anti-Semitic” villain at the end of his 1944 “The Silly Goose” (“Das dumme Gänslein”) – but which audiences could as easily interpret as a Nazi villain, since he is depicted as a non-ethnic establishment fox deceiving the naïve peasant goose.

Hans Fischerkoesen of the Fischerkoesen-Film-Produktion studio, considered wartime Germany’s best animator, steadfastly refused to include anything martial in his cartoons, and only “officially” featured an “anti-Semitic” villain at the end of his 1944 “The Silly Goose” (“Das dumme Gänslein”) – but which audiences could as easily interpret as a Nazi villain, since he is depicted as a non-ethnic establishment fox deceiving the naïve peasant goose.

The most blatant propaganda cartoon had to rely on our own animal characters! The 1944 animated cartoon “Nimbus Libéré” (roughly “From the Dark Clouds Raining Down”), directed by Raymond Jeannin in Germany to be shown in Axis-allied Vichy France, showed the well-known American cartoon characters Mickey Mouse, Donald Duck, Goofy, and Felix the Cat (also Popeye) as inept U.S. aviators carelessly bombing the French civilians they are trying to liberate.

About Reynard the Fox

In the Netherlands, during the 1930s a fervent Nazi-equivalent Nationaal Socialistische Beweging (NSB) member, Robert van Genechten, became the editor of the Dutch right-wing party’s literary magazine, Nieuw-Nederland (New Netherland). Wanting to show that Dutch Socialists could be just as creative as the German Nazis, he championed independent projects. In 1937, inspired by Hitler’s speeches about the coming New Order in Europe, van Genechten set out to promote it in the pages of Nieuw-Nederland, writing a long talking-animal fable that was blatant propaganda.

About Reynard the Fox, Baldwin the Regent, and Jodocus (Van den vos Reynarde: Ruwaard Boudewijn en Jodocus) was published in the November 1937 issue of Nieuw-Nederland. Supposedly a modern sequel to the medieval Reynard the Fox folk tale, first written down around 1150 A.D., the story takes place just after the death of King Nobel, the lion monarch of the original tale. Baron Reynard is keeping a low profile under house arrest in his castle at the time. Noble’s heir, Prince Lionel, is too young to rule, so the Animal Kingdom is placed under a regency led by Prime Minister Baldwin the Ass, a pompous and idiotic aristocrat. Into the Animal Kingdom come a wandering tribe of rhinoceros merchants, led by the oily Jodocus (which in Dutch means roughly “Jew-animal”). There are a lot of nudge-nudge-wink-wink comparisons of the rhino’s big nose-horns with the Nazi caricatures of big-nosed Jews. Jodocus flatters Baldwin, who is easily taken in, and soon the rhino merchants have taken over the Animal Kingdom’s economy and infiltrated the upper classes.

About Reynard the Fox, Baldwin the Regent, and Jodocus (Van den vos Reynarde: Ruwaard Boudewijn en Jodocus) was published in the November 1937 issue of Nieuw-Nederland. Supposedly a modern sequel to the medieval Reynard the Fox folk tale, first written down around 1150 A.D., the story takes place just after the death of King Nobel, the lion monarch of the original tale. Baron Reynard is keeping a low profile under house arrest in his castle at the time. Noble’s heir, Prince Lionel, is too young to rule, so the Animal Kingdom is placed under a regency led by Prime Minister Baldwin the Ass, a pompous and idiotic aristocrat. Into the Animal Kingdom come a wandering tribe of rhinoceros merchants, led by the oily Jodocus (which in Dutch means roughly “Jew-animal”). There are a lot of nudge-nudge-wink-wink comparisons of the rhino’s big nose-horns with the Nazi caricatures of big-nosed Jews. Jodocus flatters Baldwin, who is easily taken in, and soon the rhino merchants have taken over the Animal Kingdom’s economy and infiltrated the upper classes.

The rhinos persuade the animal nobility that marriage to one’s own species is very old-fashioned, and soon the animals are having cat-chicken, goat-fish, and other mongrel children, all of whom are ugly and stupid, illustrating the Nazi “science” of Racial Purity. Reynard, who has been quietly watching, is the only one smart enough to recognize that the rhinoceroses are sabotaging the Kingdom’s social order so they can take over. Reynard rallies the honest National Socialist animal commoners, who revolt against and kill the rhinoceroses.

Unfortunately for van Genechten, the Nazis did not appreciate this independence. They wanted underlings, not equal partners. When van Genechten submitted his novel for publication in a German edition, the Nazi censors rejected it. They condescendingly congratulated him for meaning well, but said that he obviously did not realize that the International Jewish Menace and Racial Purity were too serious to be treated as satire. Also, Reynard the Fox was too-well established through centuries of folklore as a thief, murderer, liar, and betrayer to become a heroic Nazi role-model. Van Genechten was proud of his novel, and felt insulted, but there was little he could do about it at the time.

In 1940, the situation changed. The German military had just invaded and conquered the Netherlands, and the Nazis needed willing Dutch allies to fill their collaborationist government. Van Genechten volunteered and was appointed the new national Procurator-General. During the War he signed a lot of death warrants against Resistance fighters and Dutch Jews, which got him his own death sentence from a war-crimes tribunal in October 1945. Van Genechten committed suicide before the sentence could be carried out.

While he was riding high, though, he used his influence to get About Reynard the Fox (the title was shortened) published as a handsome book, illustrated by Maarten Meuldijk (De Amsterdamsche Keurkamer, March 1941, 98 pages). There were two printings of 10,000 copies. It was on sale throughout the Netherlands and the Flemish-language part of Belgium from March 1941 through the Liberation in May 1945, when it abruptly disappeared. It has been officially unavailable since then, although copies occasionally turn up from Dutch antiquarian booksellers for about $20.

Van Genechten also pulled strings to have About Reynard the Fox made into the first Dutch animated “feature film” (although it was only 13 minutes long), by the Nazi-created Nederland Film propaganda studio, directed by Egbert van Putten. Production lasted from 1941 until April 1943. It was completed in Agfa-color, but never released. The Germans had the negative and sound track taken to Berlin, where they disappeared during the last days of the War. They were rediscovered in bits & pieces between 1991 and 2005, and the finished film was first shown at the Holland Animation Film Festival in Utrecht in November 2006 for an academic audience. The reviews are that it is very well-made, but very anti-Semitic. The major change from the novel is that the novel has the cast as natural, unclothed, four-legged forest animals, while the animated cartoon has them as bipedal, medieval-clothes-wearing funny-animals.

Italian and Japanese cartoons

Italian animated propaganda did not feature funny-animal casts, although in INCOM’s 1941 “Il Dottor Churkill”, directed by Luigi Liberio Pensuti, an evil Winston “Churkill” drinks a 'democracy' potion, turning him into a “Mister Hyde” murderous gorillalike (but still cigar-smoking) monster.

Japan was ruled by an Imperial military government during the War. This was good news for Japan’s few independent animated-film makers, because the Naval Ministry considered animated cartoons to be excellent for instilling the proper patriotic spirit in children. All civilians were under wartime orders, but animators were put to work making cartoons instead of being drafted into the military or sent to weapon factories.

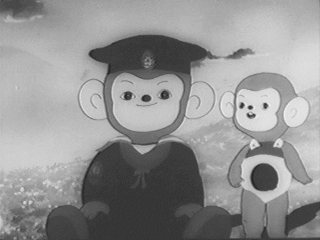

Two animated “features” were produced during the War under Imperial Naval guidance, and were distributed by officially-civilian theatrical chains. Both were directed by Mitsuyo Seo and featured Japanese folk-tale child-hero Momotar? (“Peach Boy”) as a modern boy-Admiral leading a force of cute animal Imperial sailors.

Momotaro’s Sea Eagles

Momotaro’s Sea Eagles (Momotar? no Umiwashi), March 1943, is a 37-minute retelling of the attack on “Devil Island” (Pearl Harbor). The film shows several different kinds of animals as sailors, implying that the Imperial Navy represented all the Asian nations “liberated” from their Western colonial masters, but the emphasis is on the monkey aircraft pilots (the “Sea Eagles”) who represent the Japanese pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor. Actual Japanese newsreel footage of the attack was rotoscoped into the movie. The Fleischer Studios’ Popeye cartoons were popular in Japan during the 1930s, and Momotaro’s Sea Eagles shows Popeye, Olive Oyl, and Bluto frantically trying to escape the monkeys’ bombs.

Momotaro’s Sea Eagles (Momotar? no Umiwashi), March 1943, is a 37-minute retelling of the attack on “Devil Island” (Pearl Harbor). The film shows several different kinds of animals as sailors, implying that the Imperial Navy represented all the Asian nations “liberated” from their Western colonial masters, but the emphasis is on the monkey aircraft pilots (the “Sea Eagles”) who represent the Japanese pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor. Actual Japanese newsreel footage of the attack was rotoscoped into the movie. The Fleischer Studios’ Popeye cartoons were popular in Japan during the 1930s, and Momotaro’s Sea Eagles shows Popeye, Olive Oyl, and Bluto frantically trying to escape the monkeys’ bombs.

Momotaro’s Divine Warriors

Momotaro’s Sea Eagles was so popular that the Naval Ministry followed it up with a full-length feature, and provided the animators with all the scarce production materials they needed. The 74-minute Momotaro’s Divine Warriors (or Momotaro’s Gods-Blessed Warriors, Momotaro’s Sacred Sailors, or other translations; Momotar?: Umi no Shinpei, April 1945), is a sequel showing the funny-animal Imperial Navy occupying the Dutch East Indies and conquering Singapore.

The feature is in several segments with abrupt shifts, implying that production was divided among several different units. It opens with four young naval cadets, a monkey, puppy, bear cub, and pheasant (the four animals in the Momotaro folk-tale), returning to their home village to say good-bye before shipping out. The action jumps to the bunny Imperial Navy constructing a tropical base and air strip while Indonesian animals (elephants, rhinoceroses, tigers, leopards, wallabies, crocodiles, gibbons, proboscis monkeys and surilis, etc.), some in distinctive Indonesian native dress, look approvingly on and help out. Admiral Momotaro and additional funny-animal troops (including the four friends) arrive. The sailors set up a language class to teach the simple but happy natives their ah-ay-ee-oo-uu and their first word of the Japanese language: a-sa-hi (rising sun). The Japanese sailors react to the steamy equatorial climate and the strange Indonesian flora and foods. The pleasures of a military base life are shown; washing clothes, getting mail from home, etc. The pilots successfully carry out their first mission against the enemy.

A sudden shift to silhouette animation set 300 years earlier shows the independent Southeast Asian sultanates being tricked into submission by Dutch merchants; the Japanese “why we fight” rationale. The feature returns to the present to show the serious preparation for a major offensive and the departure of the air armada. The battle is obviously against the British at Singapore; the enemy is shown as British-uniformed human Big-Nosed Foreign Devil (with a demon’s horn) soldiers. The pompous British officers cravenly try to avoid responsibility as they surrender. The final scene shows the villagers back home getting news of the victory on the radio, while animal children play at being paratroopers jumping on a map of the United States – the next target! The Japanese public must have considered this bitterly ironic; the movie was released in April 1945, when the U.S. Air Force dominated the skies over Japan and everybody was waiting for the expected Allied invasion of the Home Islands.

Momotaro’s Sea Eagles and Momotaro’s Divine Warriors were suppressed after the War by the Occupation authorities, and were considered lost films until the 1980s, when they were quietly re-released on the new home video market. They are both available today; the former forms part of The Roots of Japanese Anime, released in the U.S. in 2008, while the latter is online in nine videos.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

Excellent and informative write-up. Thank you!

On a personal note, I didn't know of Mister Ed's Mount Kisco origins -- that's where I was born and grew up.

Yes. In Walter Brooks' 1937-1945 magazine short stories, Wilbur POPE lived in Mount Kisco, just north of New York City, and took the commuter train daily into the city to his Monday-Friday job. About the series' only wartime reference was one story in which Wilbur rides Mr. Ed from his home to the Mount Kisco train station instead of driving to save on rationed gasoline.

In the TV comedy, Wilbur POST moves out of the city (unspecified but strongly implied as Los Angeles) to "17230 Valley Spring Lane" in an unnamed suburb "to get a little closer to nature". He drove his own car, naturally, both because everyone in Southern California drives, but mostly because the TV program was originally sponsored by Studebaker. Guess what kind of car Wilbur drove prominently?

Fred Patten

Post new comment