Review: 'Amazing Dogs', by Jan Bondeson

Amazing Dogs: A Cabinet of Canine Curiosities

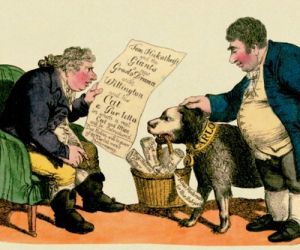

Illustrated with contemporary images.

Jan Bondeson (Cornell University Press, May 2011)

Hardcover $29.95 (286 pages)

Bondeson is a Cornell University lecturer who has written several books about historical oddities (“The Two-Headed Boy, And Other Medical Marvels”, 2000; “Buried Alive: the Terrifying History of Our Most Primal Fear”, 2001; etc.). Here he documents examples of headline-making dogs, emphasizing intelligent and “talking” dogs but also including notable meat-roasting dogs, rat-catching dogs, famous people’s dogs, martyred dogs, and more.

The intelligent and “talking” dogs will be of most interest to Furry fans. Bondeson notes that reports of these date back to antiquity, but these “true stories” contain so much obvious fantasy that none of them can be taken seriously. He cites the 18th century as about as far back as contemporary news reports and theatrical posters go.

The earliest is a 1729 report of a marvelous performing dog. By 1750 a “Chien Savant” from France was astounding English audiences by spelling words and answering questions by picking out cardboard letters. The next year, a rival “Learned English Dog” border collie toured England with a larger vocabulary and the ability to answer questions in Latin and Greek, not to mention reading members of the audience’ minds!

This sort of stage show went on to the end of the nineteenth century. The most famous was the dog Munito, a poodle or water spaniel-poodle mix who performed from the 1810s to the late 1830s. Bondeson wryly notes that nobody seemed to notice that this was twice the lifespan of normal dogs, or that the illustrated handbills showing Munito throughout his career depicted at least two if not three separate dogs. These were all stage performers, and the dogs’ masters never allowed themselves or their dogs to be closely examined for any trickery. By 1900 the public was more sophisticated and demanding of proof against fakery.

The early 20th century was the era of eccentrics – mostly from Germany – who really believed their dogs had super-human intelligence and could talk. Frau Paula Moekel of Mannheim insisted that her Airedale terrier Rolf could discuss mathematics, ethics, religion and philosophy. When World War I broke out, Rolf at first was enthusiastic about German military superiority, but he later decided that the war was too bloody and became a pacifist. Moekel wrote Rolf’s biography, publicized him widely, and allowed skeptical scientists to examine him although she was the only one who could interpret his barks into German speech for them. The scientists allowed that Rolf was very intelligent for a dog, but not to any exceptional degree, especially since his opinions always echoed Frau Moekel’s own.

Rolf had several “children” – puppies – and one of them, Lola, was adopted by Henny Kindermann, another believer in the “new animal psychology” who claimed the same ability to talk with Lola that Moekel had had with Rolf. The “new animal psychology” was popular with several Nazi intellectuals, one of whom, a Professor Max Müller, later claimed that “representatives of the Wehrmacht had received directions from the Führer to satisfy themselves concerning the usefulness of these educated dogs in the field.” As late as 1978, some elderly German ladies were insisting that they could talk with their dogs.

Bondeson briefly covers famous dogs of the 20th century like Rin Tin Tin and Lassie, who appeared in movies and TV but did not pretend to be more than well-trained. More pertinent were dogs like the border collie Betsy in 2008 who was acknowledged by scientists to understand more than 340 words in English and to be able to recognize many objects from their two-dimensional pictures. These were not the same as “talking dogs” like the 1910s & 1920s Don, a German pointer who could recognize several German questions and answer them in one- or two-word sentences. The answers required a stretch of the imagination to be understood clearly, but there was general agreement that Don’s ‘ja’, ‘nein’, the German words for ‘cake’, ‘walk”, and a few others were distinct barks from each other and represented meaningful responses to the questions. Don could express himself intelligently to the extent of his small German vocabulary.

There is a larger chapter on famous stage dogs. These were distinct from the performing dogs in that they acted in plays. They go back to Shakespeare’s “Two Gentlemen of Verona”, which has a small part for a dog named Crab. By the 19th century, dogs featured in starring roles in plays written especially for them. The prime thespian was Carlo, a large Newfoundland dog whose career lasted from 1803 to 1811. A children’s author wrote “The Life of the Famous Dog Carlo”, which was impossibly heroic and melodramatic. Carlo’s roles included attacking villains, jumping into rivers to rescue drowning men or children, and similar actions. But Carlo was temperamental and attention-hungry. “The audience were delighted when the acting dog was up to mischief, and some people came to see the play again and again to see what rowdy behaviour Carlo would be up to next.” Other notable 1800s acting dogs on both sides of the Atlantic included Bruin and Yankee. In those politically-incorrect times, it was common for dogs to play the more intelligent of a team with a “Dumb Black” partner.

The remainder of “Amazing Dogs” is more prosaic. There are chapters on famous traveling dogs who were allowed to ride on railroads back & forth on their own, graveyard dogs who laid on their master’s tombs for the rest of their lives, “collecting dogs” from about 1860 to 1960 who were trained to go about in public with donation boxes to collect for charity (at least one dog was known to take his donations into a food shop and try to buy a treat for himself), St. Bernards and other rescue dogs, and more.

Bondeson collects some well-known stories and refutes others. For instance, he shows that the famous story of Greyfriars Bobby originated as a deliberate fiction to lure tourists to Edinburgh. Bobby was a real 1860s Skye terrier who lived in the Greyfriars churchyard, but he wandered throughout it catching rats and accepting handouts from neighboring animal-lovers. There was no beloved master whose grave he laid on.

The anthropomorphic aspect is slight, but there is enough here about interesting dogs to make “Amazing Dogs” worthwhile reading for Furry fans. The book is profusely illustrated with old theatrical handbills, 19th century magazine engravings, and 20th- & 21st century photographs, including 39 color plates.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

They're not really "talking", or "reading". Dogs lack the language center that enables such abilities in humans--Don was simply trained to respond a certain way to a certain stigma to acheive a certain perceived end. He wouldn't be able to understand that he'd just spoken a word, or even what a "word" is.

Don was a public sensation in Germany during the period when the "new animal psychology" was held in regard, when a "reputable researcher" could claim to have asked a dog, "Who is Adolf Hitler?" and gotten the answer, "Mein Führer!".

Fred Patten

Be that as it may, I doubt the dog had any idea what it was "saying" other than it was supposed to react that way when given the command.

Pet rocks were once a sensation. Does that make them sentient?

When people put things in quote marks, and they aren't actual quotes, the general thought is often that they mean you to take them with a grain of salt.

This goes double when the "reputable researcher" is also a Nazi.

However, I would like to thank you for giving me the opportunity to call someone a Nazi on the Internet and actually be correct!

Post new comment