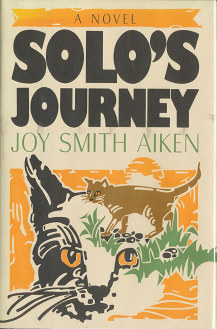

Review: 'Solo's Journey', by Joy Smith Aiken

The lives of the Quorum cats are filled with paradoxes: Although feral and untamed, they live within sight of the Owners’ dwellings and feed off the scraps in the Keep; although peace-loving, too often the Quorum enforcers and bards are forced to protect and defend their territory from the ravages of invading gypsy cats from outside the territory. But the plight of the Quorum becomes desperate when the Owners attempt to demolish their territory and threaten the lives of the cats themselves. It is left to Solo to lead them to safety, as he tries to persuade them to abandon their homes and traditions and learn to survive beyond the Owners’ domain. Even as their dens go up in flames, Solo helps the Quorum cats execute their escape; slipping into the welcome cover of darkness, the feline exiles now begin their tortuous quest for a new land. (blurb)

Solo’s Journey is a talking-cat fantasy, in the tradition of Tad Williams’ Tailchaser’s Song and so many others (why are there almost no talking-dog fantasies?), going back ultimately to Richard Adams’ Watership Down for its “realistic” animal species with a detailed language.

G. P. Putnam’s Sons, November 1987, 255 pages, 0-399-13321-6, $17.95. Map by Scot Aiken.

But Aiken carries it to an extreme:

I ought to slap the siltaa out of you, if you have any left! A warrior died here tonight because of you – because you don’t have enough sense to stay with your mother. Get back to your thraille, kit, before someone else gets hurt trying to keep your wet rear end in one piece.’ (p. 18)

This is Solo’s biography, from his kithood in a forest den near “a vast complex of Owner dens known by the ferals as the Dwelling” (p. 14), to his coming to live in a “Quorum” (the humans have a collective noun for this; a clowder of cats) of feral cats in that town, to his becoming the leading Dom (alpha tomcat) of that Quorum. At the beginning of the book, practically every paragraph introduces a new cat word and defines it by implication:

The ground on the other side of the Fence was covered with a hard, smooth substance his mother called ‘greyrock’, and not so much as a blade of grass grew from it. Along the edge of the greyrock stood many of the giant, roaring monsters the ferals knew as ‘rauwulfen,’ which had frightened him so badly the first time he had seen them with his mother. But they all sat quiet and lifeless now, though still reeking of smoke and fire. Solo took courage from how fearless the elders had been around the rauwulfen when they slept silently, as they did now. (p. 14)

By the end of just the first chapter (pages 11 – 25), the story feels like the old nursery tale of “Hot Cockalorum”, with so many nouns replaced by nonsense equivalents that it is almost like a new language.

At the time when Solo’s mother and sisters disappear, and he wobbles into the Quorum to keep from starving, he is just a kit; and the Quorum is ruled by Dom Bryndle and his bards (secondary tomcats) like Dom Spanno. (Presumably “bards” because the tomcats rowl loudly at each other as they fight.)

Spanno was second in rank only to Dom Bryndle himself, and the kit watched in awe as the young bard slowed and stopped five cat-lengths from the gypsy, his calico head down almost to ground level, his eyes locked in challenge. The two bards faced each other in classic feral style, every muscle tense and ready, their tails twitching spasmodically as each tried to read the intent of the other. Two more warriors moved into the periphery of Solo’s sight. (p. 17)

Gypsies are enemy cats; loners or from rival Quorums. The early part of Solo’s Journey introduces the reader to the politics of his Quorum.

The three took off across the field, with Spanno, as usual, in the lead. They were the Enforcers of the Quorum, if it could be said that Dom Bryndle had such a group at all. The Quorum itself had long been peaceful and the need for such police-state tactics was minimal. There was also a tinge of rivalry between the Dom and the calico, and their relationship was slightly strained. It was assumed that at some point Spanno would inherit Bryndle’s mantle, and the Dom kept the younger bard at a distance, although only slightly more so than he did everyone else; Bryndle by nature was a loner and remained aloof from the most social aspects of Quorum life. (p. 20)

About the first half of the story follows Solo’s slow rise through the ranks. Aiken is good with dialogue:

The kit was very flattered at the great Spanno showing such an interest in him, and he was feeling taller by the minute.

‘I was just going when you got here, Dom Spanno,’ he answered in a painfully kittenish voice.

‘Better drop that ‘Dom’ stuff – Bryndle would slap you fey. Just call me Spanno. Call those two anything you like, they’ll answer.’

‘A simple ‘master’ will do,’ offered Ponder.

‘Okay, ‘Simple Master,’ roared Selwyn.

‘Aren’t they clever?’ Spanno said dryly. ‘Come on, Solo. I’m thirsty, too, and I need a break from these two. Let’s go to the Dwelling.’ (p. 29)

But a constant menace to Quorum life is that of the omnipresent Owners. Sometimes they (or some of them) feed and care for the ferals; at other times they (or others among them) try to kill the ferals.

The Legends told of such things, of horrible atrocities designed for killing. He knew that horrors like that did not exist naturally, but were created by the Owners. And that brought Solo face-to-face with the Great Paradox. Everybody knew that feline existence was inextricably bound to Owner Culture, but the how and why of it were beyond him. These great and malevolent God-beings were feared above all else, and yet the Quorum itself was anchored to the periphery of their strange and incomprehensible world, seemingly without thought of leaving it. Clearly, the Legends had much to teach him. (p. 24)

(I have personally observed this. I lived for over thirty years in an apartment building in a block of similar apartments, with an alley running behind them. The alley was constantly inhabited by feral cats, who expected to be fed but never let any humans approach them too closely. Some of the constantly-changing tenants thought the cats were cute and tried to feed and befriend them, while others threw rocks at them, tried to poison them, and frequently called the police to demand that they be removed.)

Solo is conveniently special.

Now everyone began to understand what Solo meant. While all felines see radiant, ever-changing colors around living things, only a few could see the more static, monotoned emanations given off by inanimate objects, in this case metal, which sparkled electric blue. Solo evidently had such an ability. (p. 34)

Solo’s ability to see metal traps puts him on the inside track to leadership in his Quorum. There are many colorful and often amusing adventures as he grows to maturity: the Night of the Giant Rat, the rivalry with the North Quorum, his discovery of sex with the motherly Kitty-Kitty, his first fight against an equally-young and reluctant gypsy, the relations between the ferals and the Owners’ Tame-cats, Bryndle’s madness and Solo’s near-death. But Solo is always warier than the other ferals of the Owners:

‘What brings you here alone?’ asked Kitty-Kitty. ‘Did the bards abandon you?’

‘No, it’s just so nice way out here,’ answered Solo, inhaling deeply. ‘Sometimes I wish the Woodstack was farther away from the Dwelling.’

‘I know,’ Kitty-Kitty said. ‘The burned rack of the rauwuffen is so heavy at times it hurts my throat.’

‘It’s not just that,’ replied Solo. ‘Everything seems to be touched by the Owners – the greyrock, the Wall, even the trees for the Woodstack. I don’t think we should live so close to them…’ (pgs. 137-138)

Eventually Solo rises to Dom-hood within the Quorum. And just in time, because the Dwelling gets new Owners who are unfriendly toward the ferals.

[…] the new attitude the Owners seemed to have about the ferals greatly worried Solo. He issued orders that the greyrock was off limits to the ferals, except at mid-darkfall when they went to the Keep for graille. Perhaps, he thought, the situation would get back to normal when the Owners had finished with their Dwelling. Already it looked much as it had before. The burned Woodstack, finally, had been taken away. Except for the change in the Owners, a semblance of normality had returned to the territory. (p. 175)

When the new Owners become unmistakably hostile, Solo realizes that it is time to separate from Owners altogether and become a truly wild Quorum. But you know the saying about herding cats. Solo has to persuade the rest of the Quorum that he is right. And it is a difficult trek with all the Quorum’s young kits. But I am sure that I am not spoiling anything when I say that there is a happy ending.

Solo’s Journey is certainly not the only talking-cat fantasy for cat-lovers, but it has enough action and non-cute dialogue to appeal to Furry fans, too.

About the author

Fred Patten — read stories — contact (login required)a retired former librarian from North Hollywood, California, interested in general anthropomorphics

Comments

Post new comment